'Begin with Bach' - The Chopin and His Europe Festival (Chopin i jego Europa Festival ) Warsaw, Poland 20 August - 6 September 2025

'Begin with Bach'

|

| The Bach House in Eisenach [Bach's birthplace] Thuringia, Germany |

|

A quite extraordinary J.S.Bach portrait as generated by computer (not AI) from his skull, contemporary paintings and descriptions |

We begin and end this year's 'Chopin and his Europe' Festival with Bach.The brilliant composer, who occupies a very important place in the Chopin universe, will also be present in an important, sometimes in an unobtrusive way, on each day of the festival events.

The programme of this year's Festival is created with the intention of presenting Chopin's works in a multifaceted context of music from Bach to Lutosławski. The 29 concerts will be filled with Polish and European music in the interpretations of traditionally two stylistic trends: contemporary and historically informed.

|

The Bach House in Eisenach [Bach's birthplace] Thuringia, Germany |

An important aspect will therefore be historically informed performance, represented in 2025 by soloists and ensembles with well-deserved reputations; performances will include:

Dmitry Ablogin, laureate of the 1st International Chopin Competition on Historical Instruments with the Freiburger Barockorchester (with both Chopin concertos), Giovanni Antonini's Il Giardino Armonico (Felix Janiewicz's Violin Concerto No. 5 interpreted by Alena Baeva), a leading Polish ensemble of this performance style: Martyna Pastuszka's {oh!} Orchestra (with Felix Janiewicz's Violin Concerto No. 4, interpreted by Chouchane Siranossian, and Beethoven's Piano Concerto in B-flat major, performed by Tomasz Ritter, winner of the First Chopin Competition on Historical Instruments).

We will also hear, after a long break, Concerto Köln with a particularly interesting juxtaposition: Janiewicz's Third Concerto in violin (with Evgeny Sviridov) and piano version, commissioned by the Institute and presented for the first time (with Tomasz Ritter).

Martin Nöbauer, a young pianist with an interesting personality, finalist of the 2nd Chopin Competition on Historical Instruments, will play his debut recital at the Festival.

A special place in the programme – which is a kind of reference to the 20th Festival – is occupied by two Bach recitals by Władysław Kłosiewicz, who will perform both volumes of Bach's Das Wohltemperierte Klavier on the harpsichord. This unique work, so important in Chopin's teaching practice, found its continuation in Shostakovich's Preludes and Fugues, arranged analogously to the Bach cycle in two volumes. Yulianna Avdeeva will present them at the festival in two recitals, creating an interesting context of creator-participant (it is worth remembering that Shostakovich took part in the First International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition in 1927) and performer-winner.

'Chopin and his Europe' is pianism of the highest order; the year of the Chopin Competition will see its triumphs: alongside Yulianna Avdeeva (three times, including a very special chamber programme with Krzysztof Chorzelski dedicated to Andrzej Tchaikovsky), Bruce Liu will play with the Apollon Musagète Quartet (including Schubert and Mozart), Dang Thai Son and the young Sophia Liu will play both Chopin concertos with Marek Moś's Aukso Orchestra; with this ensemble, Kyohei Sorita and Aimi Kobayashi will perform Mozart's Concerto for Two Pianos (the same concert will feature the first performance of Lutosławski's Partita in the version for cello, interpreted by Andrzej Bauer); in recitals, we will hear Kate Liu, Eric Lu, Ivo Pogorelic (in a programme including Bach and Chopin) and Ingrid Fliter (Chopin recital).

There will also be many virtuosos not associated with the Competition, notably Ukrainian pianist Vadym Kholodenko, who will perform Karol Szymanowski's Fourth Symphonie concertante and Ravel's Concerto for the Left Hand with Sinfonia Varsovia under Bassem Akiki; Benjamin Grosvenor will give a recital (including Schumann's Fantasia in C Major) and Piotr Anderszewski will give a Brahms recital.

The space of sophisticated chamber music will be rounded off by the Hagen Quartet with Mao Fujita, making its festival debut (in a programme featuring Brahms and Shostakovich), and the resident quartet Belcea (another interestingly formatted programme featuring works by Mendelssohn, Mozart and Dvořák's Piano Quintet in A Major – with Alexander Melnikov).

The festival will open, as has been the tradition for several years now, with a violin recital by Fabio Biondi at the Basilica of the Holy Cross, an honourable, symbolic gesture by this great artist whose contribution to the promotion of Polish music in the world cannot be overestimated. The series of festival concerts will close with a recital – also in the Holy Cross Basilica and also Bach – by the eminent Belgian cello virtuoso, Roel Dieltiens.

An important element of the Festival will be the presentation of the Polish participants in the forthcoming Chopin Competition: as in the case of the previous edition of the Competition, five recitals with the participation of 10 pianists are planned in the Basilica of the Holy Cross; these concerts are organised in cooperation with the Mazovian Institute of Culture.

Traditionally, selected concerts will be available for streaming online on the YouTube channel of the Fryderyk Chopin Institute, as well as in broadcasts and rebroadcasts on Polish Radio 2. Closer to the date of the Festival, we will provide information on the broadcasting schedule.

The full detailed programme of the festival is available here

https://festiwal.nifc.pl/en/2025/kalendarium/

Recital Reviews

Profile of the Reviewer Michael Moran : https://en.gravatar.c atom/mjcmoran#pic-0

All artists' photographs by Wojciech Grzędziński / NIFC

* * * * * * * * * *

I unfortunately was not unable to attend or review recitals until the evening of 22nd August 2025

Reviews were posted in reverse order of live performance (latest recital first to appear). This saved readers the labour of scrolling way down the site after each recital to read the latest review

* * * * * * * * * *

SATURDAY 6.09 9:00 p.m.

Basilica of the Holy Cross

Special cello recital

ROEL DIELTIENS

|

| The pillar in the Holy Cross Church, Warsaw, containing the heart of Chopin |

This recital, as a Bach conclusion at the highest musical level, was an uplifting and musically perfect and appropriate conclusion to this entire remarkable and unique festival. As such the unaccompanied Bach Cello Suites are beyond criticism on a night occupying a domain of music that transported us quite beyond the outstanding interpreter, our guide.

In so many ways, the entire sacred atmosphere of this church, which contains the heart of Chopin, contributed poignantly to lifting our hearts, spirit and consciousness beyond the mindless strife of the present world. Chopin feared being buried alive and wished his heart removed after death. Presently, we grimly find ourselves buried alive under suffocating earth, gasping for escape from airless confinement beneath the lowest moral values of human nature. Where will our hearts lie?

Here, during a festival that opened and concluded with mighty Bach, we contemplated in sublime music, the highest in human creative inspiration which will hopefully continue to light and fuel future fires of hope and redemption in the soul.

|

| J.S.Bach at his birthplace in Eisenach |

Programme

Domenico

Gabrielli [1659–1690]

Ricercare

No. 7 (1689)

Johann

Sebastian Bach [1685–1750]

Cello

Suite No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1008 (1723)

Prélude

Allemande

Courante

Sarabande

Menuet I

Menuet II

Gigue

Cello

Suite No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007 (1723)

Prélude

Allemande

Courante

Sarabande

Menuet I

Menuet II

Gigue

Cello

Suite No. 4 in E flat major,

BWV 1010 (1723)

Prélude

Allemande

Courante

Sarabande

Bourrée I

Bourrée

II

Gigue

A thought after my visit to Bach's birthplace, Eisenach

A selection of Bach's collection of religious texts used as a source for his Cantatas, Passions and Masses at his birthplace, Eisenach

6.09 SATURDAY

6:00 p.m.

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hal

Piano recital

IVO POGORELIC

The 'scandals ' associated with this pianist are so well known I shall not try your patience here by recounting them. Even at the outset, it was obvious conventional concert formalities had been rethought. As the audience began to assemble, Ivo Pogorelić remained seated at the piano in street clothes experimenting with touch and sound. He later appeared 'formally attired' in a simple white dress shirt and black bow tie - no jacket. Considering the radicalism of his thinking, I saw it as a divertingly ironical, intelligent and rather amusing judgment on his role.

Many years ago in the late 1960s I was writing so-called avant-garde literature. 'Indeterminate Texts' they were called. I admired the so-called French Nouveau Roman of Nathalie Sarraute, Marguerite Duras, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Michel Butor and the Irish writer Samuel Beckett. This movement influenced the Nouvelle Vague cinema of Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais and François Truffaut. In music - Boulez, Stockhausen, Kagel, Pousseur, Xenakis and Messiaen long before my close knowledge of the standard eighteenth and nineteenth century classical keyboard repertoire of say Brahms, Beethoven, Chopin and Couperin.

Pogorelić had musically taken my consciousness back to that rather exciting world of new exploratory dimensions. In 1968 I spent some time as an 'observer' at Stockhausen's Cologne Courses for New Music with the Australian composer David Ahern, which rather altered my musical appreciation and indeed musical life in some ways, attending many important premieres of Stockhausen's music.

The term avant-garde referred at that time to groups of intellectuals, writers, and artists who voiced ideas and experimented with artistic approaches that challenged the current cultural values. They also shared certain ideals or values which manifested themselves in the non-conformist lifestyles they adopted, a variety of Bohemianism and Surrealism. Stockhausen wrote of his work on Beethoven entitled Opus 1970: '...to hear familiar, old, pre-formed musical material with new ears, to penetrate and transform it with a musical consciousness of today.' A composer is always limited in the full expression of his ideas by the notation which leaves so much up to the interpretative instrumentalist. Penderecki invented an entirely new notation to express his personal musical ideas.

Where then does that invisible line of individualism interpretation lie, a line that cannot be crossed. The frontier may well have been crossed here a number of times. Significant deviation from the Urtext is today considered unforgivable and remains the ethos of much current performance practice. Standardization of interpretation through teaching, performance and ubiquitous recordings is common. Composers themselves often forbid the slightest deviation from their scores and the indications contained therein. Yet when one hears them perform, their view of their own creations can be surprising. Rachmaninoff's concerto recordings are rather free in interpretation - who am I to argue?

He showed great courage or supreme arrogance in delivering any wide-ranging deviations. These have been reduced in extent it seemed to me. But we did listen intently ...we were provoked into serious thought...which often does not happen in conventional performances of well-known works. During his 'deconstructions', harmonic transitions, emphasis of seemingly irrelevant detail, we often felt marooned. But we listened.

I felt we were witnessing a portrait of his own, deeply individualistic, internal musical landscape, filtered through a fraught and sensitive life experience. His remarkable performance of the Chopin sonata in B-flat minor Op.35 and this entire recital winged far beyond the customary and forced one to think outside the conventional interpretative carapace.

MM: I have quoted and occasionally paraphrased extracts from a particularly enlightening interview entitled 'I rejected what I was told' that Pogorelich had with pianist, music critic and teacher Igor Torbicki 19.10.2023

MM Motivation

IP: Pianists were looking for instrumental solutions on their instrument which are hard to come by, difficult to conquer, to comprehend. And I was never afraid of that. So that is what I'm doing, if one wants to understand what I'm doing.

MM: On recordings

The great pianist and musical artist Grigory Sokolov clearly feels the same as he only releases live recordings

IP: There is less freedom in the recording. it's an artificial thing. Consider that recording is something artificial. It's a box. Information goes into it and out of it, speaking in simple terms. In it, I cannot take as much freedom as I can take on the concert stage. There can be no improvisation. Recordings are documents rather than anything else.

I (MM) conceive time as a spiral and not linear in nature

Hence for me great creative artists of the past are our contemporaries (certainly if one takes geological time as a scale).

They are not 'past masters' but part of an eternal presence

IP: Because I think that Bach, for example, is contemporary. I think that Beethoven is contemporary.

MM: Establishing the invisible line that divides the composer's intention and the personal freedom of the interpretive artist. The line must not be crossed without unacceptable distortion of intention and musical speech but where does it lie ?

IP: But what I have to is to do justice to composers. I have to be respectful to them. And in order to be respectful, I have to find this golden line. Go inside, try to touch their inspiration. And then interpret it on the piano.

|

| François Boucher - Allegory of Music 1764 |

MM: The vital cultivation of sound and tone

Teachers tend to neglect this conduit for a composer's and interpreter's individual voice

In his book The Art of Piano Playing (English translation, London 1973) the great Heinrich Neuhaus devotes an entire substantial chapter on Tone production (pp 54-82).

The chapter opens: Music is a tonal art. It produces no visual image, it does not speak with words or ideas. It speaks only with sounds.

Chopin in lessons with his pupils concentrated on the production of a beautiful tone on the Pleyel which required 'work'

Q IT: What do you think has changed the most in your playing since the time of Chopin Competition?

IP: The real question is the quality of sound. Now, the quality of sound is not a result of inspiration, it's a result of hard work: listening and searching. And this is how you enter into the beautiful world of sounds. And it's all sound, Bach is sound, Chopin is sound .... And that is what’s important when you listen to my recordings – the quality of sound. And clarity. It doesn't come easily

The sound. I was constantly searching for sound variety. The quality of sound is also related to time. It does not exist as a result of inspiration or some kind of spontaneous relation. Instead, it’s mathematically calculated, and it exists within its time. It’s born, it lives, and it perishes.

So, the sound has a slot, like an airplane. The tower confirms to the pilot: “now it's your time for takeoff”. And he cannot do it together with other pilots, so there cannot be 10 flights departing at the same time. It's the same thing with sound.

Bach said that playing the piano is touching the key at the right moment. It's not only that. It's also about the right touch so that each sound has its own voice, role, and also forms a part of the sound picture. It becomes a part of a chord, harmony and melody at the same time.

That is why the school of Franz Liszt is superior to other piano schools. Because Liszt treated the piano both as an orchestra and as a human voice. That started with Beethoven. Liszt developed it further. He is responsible for the piano becoming the king of all instruments.

Chopin did his part, also experimenting with sound. Chopin did not specialize in fugues nor any orchestral composition... But on the piano, he reached enormous heights thanks to his imagination and introspection.

Q. IT: Since we’re talking about interpretation and sound, I wanted to ask you..

IP: I was now talking specifically about the quality of sound. Young people like to copy. And then they come to a difficult moment if they try to copy any recordings including my own... They listen to them a hundred or a thousand times, but they can't really reproduce them. They don't have the knowledge of how to get the sound out of the piano. And it's an anatomical thing.

Q. IT: Purely physical?

IP: Controlled by your ears and by your intellect. But in reality, there is a strict protocol that comes from anatomy. Strong muscles, connections, fingers. Then the shape of hand – sphere, like a cupola, St. Peter’s Cathedral. Centre of power in the hand. You see? [presents his hand in the playing position] Three principal muscles. Fingers are attached to muscles, they don’t play from air. It’s easy to illustrate, but very difficult to implement.

Certain lines have been broken by the first and second World Wars. Centers of culture, where the art of performing was really brought up, where competition existed, and where artists functioned, were dispersed. People emigrated.

So, certain European cultural centers just stopped existing. They were deserted. Many people emigrated to the United States, for example. Of course, they planted some seeds, but the ambience was different. The architecture of piano schools was threatened and finally destroyed. Centers of power, of piano playing knowledge like Saint Petersburg or Vienna stopped existing. World Wars interrupted their development completely.

Q. IT Do you think it's possible to rebuild those centers of piano playing?

IP: No. It would take centuries. We would need a new Beethoven, a whole new set of things. Technology is also standing in the way.

I was almost 16 or 17 years old when I realized that I knew nothing about the piano. I said to myself: “you want to fly and you don't even know how to walk”. And that changed everything. Doors of knowledge and culture were suddenly open to me. This is a fact of life, of destiny.

Q. IT: On the other hand, it seems like in history of music there are some people that were tremendously successful in passing on their knowledge with virtually complete success. One of them was Nadia Boulanger. At certain point it seemed that almost everybody who studied with her, thanks to her knowledge, was capable of achieving their artistic goals

IP: She probably had a rare talent in communication, but she was also a woman. That's very important. It's easier to learn from a woman than from a man, because there is a different ego.

And she had the capacity, capability to awaken the talent in others, to encourage them. [...] she was an expert in polyphony. It came naturally to her. [...] And also to spend time, follow and lead a talented person, help him to reach another step, another level. It takes a lot of time and dedication.

Q. IT :Why do you choose to perform from scores on stage?

IP: Why not? I spend so much time with these scores. There are so many markings on them, so many variations and shades of my work. A score is the part of my work. I don’t see any reason why I should not be using them. When you play solo, maybe it’s less needed. But while playing with an orchestra, just like yesterday, it should be there.

Indeed, part of brain’s capacity is occupied with remembering musical text [...] More like a mirror. With it, the brain is less occupied.

For the full interview :

https://prestoportal.pl/ivo-pogorelich-i-rejected-what-i-was-told

Programme

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart [1756–1791]

Fantasia in C minor, K. 475

Adagio in B minor, K. 540

Fantasia in D minor, K. 397

As mentioned, the beautiful tone, refinement and velvet touch of this pianist remain unsoiled by time. The tempo was far more considered, almost passive but then it had the character of an improvised Fantasia and a sense of 'searching'. I felt his to be rather an introverted meditation, conception or vision without excessive drama or sufficient expressiveness. The D minor Fantasy on the other hand was almost over expressive compared to more customary 'domestic' renderings.

Ludwig van Beethoven [1770–1827]

|

| Beethoven Pathétique’ Sonata First Edition (Beethoven-Haus, Bonn) |

Piano Sonata in C minor ‘Pathétique’

Op. 13 (1799)

Grave – Allegro di molto e con brio

Adagio cantabile

Rondo. Allegro

Such a difficult task to speak of it! Charles Rosen opens his analysis with a quotation from Wilhelm von Lenz in 1855: 'We should not have to speak about this work after the suffering it has gone through for fifty years in boarding schools and other institutions where one learns to play the piano. Is the name of Beethoven heard there by chance? [...] Let us hasten to say that it simply magnificent.

The popularity, indeed familiarity, of this great work already seemed under threat after publication in 1799. There was a danger to its full appreciation as a deeply tragic, yet courageous utterance, only fifty years after its conception.

Beethoven may well have been at least partially inspired to write this sonata by Schiller's treatise on tragic art, Über das Pathetische. Schiller concludes that tragedy is not only the simple presentation of melancholy but contains elements of moral resistance. Tragedy does not accept the negative outcome of reversal as final but creates 'effigies of the ideal' or utopian aspirations. When contemplating the Sonate pathétique as an interpreter, one should bear in mind Schiller: '...suffering bound up with sensibility and with the consciousness of our inner moral freedom, is tragic sublimity.'

The opening meditative Grave phrases by Pogorelich were tremendously commanding. He evolved a rather deliberate tempo in the Allegro di molto con brio which in its dramatic 'earthly' contrasts, transformed Beethoven's inner passions and the unexplored heat of disillusionment expressed in the Grave opening, into firm emotional resistance. We oscillate between poles of feeling. 'The master's gaze and a cosmic wind haunt the music.' (William Kinderman).

Although beautifully lyrical and poetic in singing tone, the Andante cantabile was rather static in its development of utopian aspirations. Here Pogorelich descended into a deep, bordering on introspective, even painful, internal monologue. I yearned for a more 'resistant', joyful Rondo. Allegro. I felt the sweeping scales did not sufficiently move us emotionally from reflection to action. During this movement, Beethoven in his composition recalls phantoms of the meditative lyricism of the Adagio. However, determined resistance wins the day and overcomes human obstacles

I felt Pogorelich could have made far more of the philosophical depth contained within this already over-familiar work. The most profound interpretation I have heard is a recording made in 1945 by Rudolf Serkin, a pianist who possessed a rare insight into the heart of Beethoven's exploration of the human condition.

Intermission

Fryderyk Chopin [1810–1849

Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 55 No. 2 (1843)

The Paris critic Hippolyte Barbedette, one of Chopin’s first biographers, wrote of Chopin's Nocturnes ‘are perhaps his greatest claim to fame; they are his most perfect works’. That is how they were seen in Paris during the mid nineteenth century. Barbedette explained the reason for their success as follows: ‘That loftiness of ideas, purity of form and almost invariably that stamp of dreamy melancholy’. There are inspired long legato lines in this 'meditation' based on the rise and fall of ardent emotion

Although played and expressed in with his memorable superb tone and touch, perhaps Pogorelić could show a deeper insight into the fluctuation of sentiments reflected in these subtle waves of melody.

Mazurkas, Op. 59 (1845)

No. 1 in A minor

No. 2 in A flat major

No. 3 in F sharp minor

All pianists fond of Chopin should learn to dance the mazurka and polonaise!

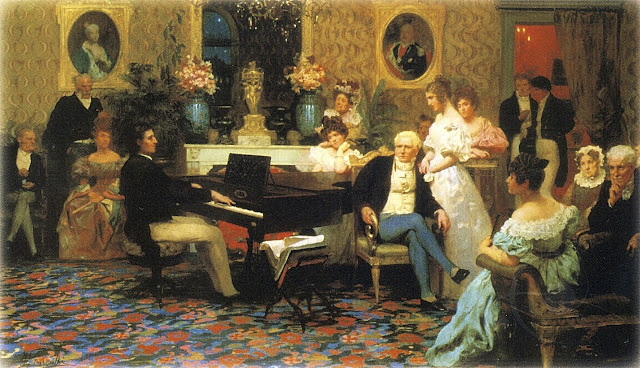

One needs to examine the nature of dancing in Warsaw during the time of Chopin. Almost half of his music is actually dance music of one sort or another and a large proportion of the rest of his compositions contain dances.

Dancing was a passion especially during carnival from Epiphany to Ash Wednesday. It was an opulent time, generating a great deal of commercial business, no less than in Vienna or Paris. Dancing - waltzes, polonaises, mazurkas - were a vital part of Warsaw social life, closely woven into the fabric of the city. There was veritable 'Mazurka Fever' in Europe and Russia at this time. The dancers were not restricted to noble families - the intelligentsia and bourgeoisie also took part in the passion.

Chopin's experience of dance, as a refined gentleman of exquisite manners, would have been predominantly urban ballroom dancing with some experience of peasant hijinks during his summer holidays in Żelazowa Wola, Szafania and elsewhere. Poland was mainly an agricultural society in the early nineteenth century. At this time Warsaw was an extraordinary melange of cultures. Magnificent magnate palaces shared muddy unpaved streets with dilapidated townhouses, szlachta farms, filthy hovels and teeming markets.

By 1812 the Napoleonic campaigns had financially crippled the Duchy of Warsaw. Chopin spent his formative years during this turbulent political period and the family often escaped the capital to the refuge of the Mazovian countryside at Żelazowa Wola. Here the fields are alive with birdsong, butterflies and wildflowers. On summer nights the piano was placed in the garden and Chopin would improvise eloquent melodies that floated through the orchards and across the river to the listening villagers gathered beyond.

Of course he was a perfect mimic, actor, practical joker and enthusiastic dancer as a young man, tremendously high-spirited. He once wrote a verse describing how he spent a wild night, half of which was dancing and the other half playing pranks and dances on the piano for his friends. They had great fun! One of his friends took to the floor pretending to be a sheep! On one occasion he even sprained his ankle he was dancing so vigorously!

He would play with gusto and 'start thundering out mazurkas, waltzes and polkas'. When tired and wanting to dance, he would pass the piano over to 'a humbler replacement'. Is it surprising his teacher Józef Elzner and his doctors advised a period of 'rehab' at Duszniki Zdrój to preserve his health which had already begun to show the first signs of failing? This advice may not have been the best for him, his sister Emilia and Ludwika Skarbek, as reinfection was always a strong possibility there. Both were dead not long after their return from the 'cure'.

Many of his mazurkas would have come to life on the dance floor as improvisations. Perhaps only later were they committed to the more permanent art form on paper under the influence and advice of the Polish folklorist and composer Oskar Kolberg. Chopin floated between popular and art music quite effortlessly.

Here in the Op.59 set we were drawn into the world of Chopin's nostalgic and poetic dreams in an affecting rendition of these ‘most beautiful sounds that it is possible to produce from the piano’ (Ludwig Bronarski). Let me allow Mieczysław Tomaszewski describe the third of these Mazurkas in F sharp minor which 'drags one into the whirl of a Mazurian dance from the very first bars, with its sweeping, unconstrained gestures, its verve, élan, exuberance, and also, more importantly, the occasional suppressing of that vigour and momentum, in order to yield up music that is tender, subtle, delicate...'

The three late Mazurkas Op. 59 (1845) were played by Pogorelich in a highly poetic and nostalgic vein with his usual luminous control of tone colour, touch and emotion. In many ways these were the finest aspects of the recital. However, I feel Poles prefer a slightly ‘rougher’, more rhythmically urgent, atmospheric mazurka, even if sublimated by Chopin.

Piano Sonata in B flat minor, Op. 35 (1839)

Grave. Doppio movimento

Scherzo

Marche funebre

Finale. Presto

The Grave opening chords certainly announced in a melancholic mood that this work was to be preoccupied with the nature of death and not a stroll in the park. In the opening Allegro maestoso, Pogorelich gave us a significant degree of emotional commitment to this remarkable movement. There was some weight, strength and menace present here. One could not, did not wish to, escape the imagery of the galloping horse.

One should reflect after this comment, that movement during Chopin’s time was restricted either to walking, horse or carriage. So when a composer wished to impart movement to a piece of music he could not envisage all of the extraordinary modes of travel we have at hand.

Of the Scherzo, the great Polish musicologist Tomaszewski comments: ‘…one might say that it combines Beethovenian vigour with the wildness of Goya’s Caprichos.’ I felt it could have been lighter in its flash of consciousness, more energetic in this shift from exuberant life towards inevitable doom.

The beautiful trio took us singing into the further dimension of ardent dreams which made the Marche funèbre such a shocking jolt from the force of destiny. Pogorelich adopted quite a fast yet successful metaphorically doom-laden tempo. The reflective trio of the Marche was only at moments a convincing contrast of innocence, love and purity blighted by the reality of death (Chopin was terrified of being buried alive – often horrifyingly possible in those primitive medical times). Tomaszewski continues perceptively: ‘The Sonata was written in the atmosphere of a passion newly manifest, but frozen by the threat of death.’

A deep existential dilemma for Chopin speaks from these pages written in Nohant in 1839. The pianist, like all of us, must go one dimension deeper to plumb the terrifying abyss this sonata opens at our feet. Pogorelich failed to take me into these dark realms very often.

Of the Presto which concludes the work, his extraordinary articulation and sound in this curious polyphonic utterance transported me into another dimension. Chopin wrote characteristically with intentional irony of the ‘chattering after the march’ leaving Schumann to write in philosophical and literary frustration: ‘The Sonata ends as it began, with a riddle, like a Sphinx – with a mocking smile on its lips’.

An outstanding and brilliantly thought-provoking recital that celebrates remarkable individualistic musical thought - rare enough today.

5.09 FRIDAY 8:30 p.m.

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Symphonic concert

ALENA BAEVA violin

IL GIARDINO ARMONICO

GIOVANNI ANTONINI conductor

Program

Feliks Janiewicz [1762–1848]

Violin Concerto No. 5 in E minor (1803–1807)

This concerto is the

finest for me of his set of five. The opening Largo is dark

and a touch forbidding. The Allegro. Moderato is highly

emotional, dramatic and a subjective Sturm und Drang melody

and put me in mind of the Mozart D minor piano concerto in its

intense emotionalism. This or even the premonitory energy within Verdi overture

to La Forza de Destino. Mozart admired Janiewicz greatly. In

fact, Mozart’s 19th-century biographer Otto Jahn speculates that his lost Andante

in A major K470 written at this time may have been composed for Janiewicz.

Michael Kelly, a

famous tenor, wrote that while in Vienna he was privileged to hear one of the

foremost violinists in the world: ‘...a very young man, in the service

of the King of Poland, he touched the instrument with thrilling effect, and was

an excellent leader of an orchestra. His concertos always finished with some

pretty Polonaise air; his variations were truly beautiful.’

The composition

certainly sets the individual soaring virtuoso violin part as a superb display

piece against the orchestra. The woodwinds were especially seductive,

impressive and romantic. Tremendous virtuosity was displayed by all the

orchestral soloists and ensemble.

The long, polyphonic,

virtuosic cadenza in this first movement is dazzling and absolutely

sensational, rather like a prized piece of decorative Sevres porcelain

displayed in a solitary cabinet in a Parisian museum. No surprise Paganini was

impressed by Janiewicz. I felt Baeva was technically completely dominant and exciting in her virtuoso execution. The

incredibly physically active conductor Giovanni Antonini remained convincing in

his flourishes with the remarkably inspiring orchestra.

Baeva presented the Adagio as

an affectingly lyrical, poetic and emotionally touching pastoral melody of love,

gliding effortlessly above pizzicato orchestral

strings. A warm, uncomplicated alluring love song. I could imagine a superb concert including this piece in the Bath Assembly Rooms where it may well have

been played. Another picturesque venue may well have been the Pleasure Gardens

of Vauxhall and Ranelagh in London.

This extraordinarily

long lyrical period by the soloist led magically attaca (no

pause) into the spirited and exuberant Rondo. Allegretto. This

conclusion suited Baeva well and her instinctive sense of rhythm and dance. The

movement emerged as rich in unmistakable folkloric, Jewish-Ukrainian dancing

elements and a physical joy. There was a beautiful balance maintained here

between the virtuosic violin soloist Baeva and the

minimalist pizzicato orchestral writing and accompaniment

under Antonini.

I felt at times I

could have been in Kazimierz in Kraków during a late evening klezmer

concert in a tavern. The accelerando conclusion was

exciting and uplifting in gaiety. the entire concerto came across as both

dramatic and theatrical and as a result highly entertaining.

I cannot imagine why

this concerto, in a fine performance by an exceptional violinist such as we

heard tonight, has not been absorbed into the conventional repertoire. Such

pleasure would be taken in hearing the sheer tuneful, ornamented virtuosity. We

do not always need to inhabit the 'dark night of the soul' in a concert hall!

Here we had a balance of temperament, the unalloyed ideal of Sturm und

Drang.

For more on the

remarkable Polish virtuoso violinist Felix Janiewicz and his long period in

Edinburgh musical life planting the seeds of the today's Edinburgh

Festival - if you have time, here is an illustrated presentation ....

Largo – Allegro moderato

Adagio

Rondo. Allegretto

Ludwig van Beethoven [1770–1827]

|

Joseph Willibrord Mähler: Ludwig van Beethoven, 1804/05, oil on canvas, Vienna Museum

Symphony No. 3 in E flat major ‘Eroica’ (1803)

Op. 55

|

| Pages from the Heiligenstadt Testament |

Beethoven was by the time of the 'Eroica' almost profoundly deaf and was communicating using the depressing conversation books.

It is well to remember a passage from the Heiligenstadt Testament of

1802:

My misfortune is doubly

painful to me because I am bound to be misunderstood; for me there can be no

relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of

ideas. I must live almost alone, like one who has been banished; I can mix with

society only as much as true necessity demands. If I approach near to people a

hot terror seizes upon me, and I fear being exposed to the danger that my

condition might be noticed. Thus it has been during the last six months which I

have spent in the country. By ordering me to spare my hearing as much as

possible, my intelligent doctor almost fell in with my own present frame of

mind, though sometimes I ran counter to it by yielding to my desire for

companionship. But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me

heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone standing next to

me heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me

almost to despair; a little more of that and I would have ended my life - it

was only my art that held me back. (Heiligenstadt

Testament © Translation John V. Gilbert)

Allegro con brio

Marcia funebre. Adagio assai

Scherzo. Allegro vivace – Trio –

Scherzo

Finale. Allegro molto – Poco

andante – Presto

In many ways not only was this composition revolutionary at the time but the performance I heard this evening was a revelation, in fact a revolution in orchestral sound quality and depth of interpretation. Beethoven began writing the 'Eroica' in Heiligenstadt, Vienna. He lived in this touristic spot from April to October 1802 while coming to terms with his growing deafness that had actually caused him to contemplate suicide. The closeness to Nature he experienced healed him psychologically. He evolved in composition what he called 'a new path' and struck out upon it with renewed courage. The revolutionary 'Eroica' symphony was one result of this catharsis.

It is instructional to read the comments by the French composer Hector Berlioz from À travers chant, 1862 :

It is wrong to tamper with the description placed at the head of this work by the composer himself. The inscription runs “Heroic Symphony to celebrate the Memory of a Great Man.” In this we see that there is no question of battles or triumphal marches such as many people, deceived by mutilations of the title, naturally expect; but much in the way of grave and profound thought, of melancholy souvenirs and of ceremonies imposing by their grandeur and sadness—in a word, it is the hero’s funeral rites. I know of few examples in music of a style in which grief has been so consistently able to retain such pure form and such nobility of expression.

From the powerful opening chords, doubtless symbolizing images of battle together with heroic 'masculine' themes, I felt enveloped in a revolutionary sound world created by the period instruments of Il Giardino Armonico under Giovanni Antonini. The contrast with the sound of the 'Eroica' created by a modern orchestra was dramatic. I will not bore you by examining each movement in detail but make a few observations as I listened to this remarkable, rejuvenated performance.

The ensemble were clearly possessed of extraordinary unity, cohesiveness and almost symbiotic connection with their conductor. All performed as one living musical organism. There was great urgency and forward momentum in their playing and a remarkable instrumental transparency revealed within the orchestral sound. The instrumentalists were pointedly apparent - for example, the remarkable accuracy of the natural horns and brass.

The revolutionary imaginative genius of Beethoven became increasingly, even disturbingly apparent in this extraordinary performance. One could imagine without great effort the shattering effect the work must have had on the original listeners. I have heard Giovanni Antonini is compared in spirit and almost demonic possession to Toscanini. He has the same striking amalgamation of passionate drive and astute perceptiveness. Antonini has a profound understanding of the revolutionary nature of the 'Eroica' as drama, when he brings a fertile imagination to bear on it. He projects that understanding into an orchestral performance that 'glows white in the furnace' (Richard Osborne).

The legato he evoked from the orchestra was affectingly expressive. I began to feel that Beethoven had entered a curious autumnal relationship in his relationship with the figure of Bonaparte, a fading green leaf once deeply admired in spring. This brought me emotionally close to his intimate embrace of Nature. His increasing love for the music of that natural force is so obvious in the Pastoral symphony.

His disillusionment with Napoleon was devastating for him. The orchestral fugal entry was magnificent and monumental. I was unexpectedly brought close to tears, something that is rarely aroused in Beethoven except perhaps during some of his late chamber works. The tympani added a percussive nobility of splendour and the force of freedom attempting to rise.

I felt the dynamic control of Il Giardino and Antonini was almost unearthly in skill. The detaché plating elevated the dance rhythms to the heights of sensibility. At this point the almost uncannily and certainly magical pitch accuracy, texture and timbre of the natural horns swept me away. The string pizzicato at pp dynamic was so elegant I often felt words were utterly inadequate to express how I felt within my emotional centre.

This performance convinced me once again that musical feeling occupies a spiritual realm beyond language to engage, inaccessible to any other medium other than of itself containing its own life. The contrapuntal polyphony seduced my mind and heart in unaccustomed ways.

The audience were hypnotized by the magnitude and new domain of sound, this rare and penetrating performance of such a familiar work. A true revelation in music, sound and imaginative conception. Surely one of the highlights of the festival for me.

THURSDAY 4.09 8:30 p.m.

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

KATE LIU

Program

Fryderyk Chopin [1810–1849]

Nocturne in F- Major Op. 15 No. 1 (1830–1832)

James Huneker (1857-1921), the renowned American music critic, writer and pianist, author of a book devoted to Chopin, wrote of the Nocturne genre:

‘Something of Chopin’s delicate, tender warmth and spiritual voice is lost in larger spaces. In a small auditorium, and from the fingers of a sympathetic pianist, the nocturnes should be heard, that their intimate, night side may be revealed. […] They are essentially for the twilight, for solitary enclosures, where their still, mysterious tones […] become eloquent and disclose the poetry and pain of their creator.’

The Nocturnes surely must be imagined as a musical poetic reflection and internal emotional agitation that takes place at night when the imaginative mind operates in relative silence and isolation at a different and sometimes fantastical level of consciousness. Chopin lived in a world without electricity. Just imagine this for a moment … The Nocturnes should retain a sense of improvisation in the internal exploration and discovery of sensibility.

The first dozen bars of the Nocturne in F minor Op.15 No.1 were written into the album of Elizabeth Sheremetev. The opening theme is melancholic and elegiac in which Liu adopted a contemplative tempo and ‘sang’ affectingly on the piano. The moment she begins to play we are convinced of her musicality and more than that. This delicate, fey lady is a musical phenomenon and an extraordinary pianist. I have written of her remarkable recitals often over the years on this website.

During the 17th International Fryderyk Chopin Competition, Warsaw, 1-23 October 2015 she was placed 3rd. At that time I had the curious vision of an immensely precocious Chopin savant whilst listening and watching her. Without doubt, hers always becomes one of the most extraordinary Chopin recitals. This pianist seems to be in touch with some force outside of herself, transfigured by the music magnetically and metaphysically, taken over by a musical 'voice' and almost cosmic natural force, if that does not sound too fanciful. She connects us to 'The force that through the green fuse drives the flower' in the words of that great Welsh poet Dylan Thomas.

Listening to her I was reminded of a description of a Chopin performance. In Paris he acquired new aristocratic students in 1847 such as the immensely talented Maria Aleksandrovna von Harder (1833-1880), a precocious 14-year-old Russian-German pianist from Saint Petersburg. She took lessons from Chopin almost every day during 1847 and up to his departure for England in April 1848.

She wrote: '....when he was in pain, Chopin often gave lessons by listening in the office adjacent to the drawing-room .... his hearing, sensitive to the subtlest shadings, immediately recognized which finger was on a given key.' In 1853 Hans von Bülow described her playing to Liszt, an approach that she surely must have partly imbibed from Chopin '...one of a kind . . . full of all the whispers . . . phenomenal, transient and sudden changes in tempo, unlike what you usually hear in concert halls. Luminous, interwoven, wonderful melodies emerged like miraculous swan songs.'

Nadia Boulanger was once asked what made a great as opposed to an excellent performance of a piano work. She answered 'I cannot tell you that. It is something I cannot describe in words. A magical element descends.' This is certainly the case with Kate Liu.

This atmosphere of poetic nostalgia in this nocturne soon gave way to a depiction of the dark night of the soul and turbulent emotions. The contrast in atmosphere was profoundly meaningful and at times intensely lyrical. Liu seemed to explore the darker regions of the heart in a dramatic fashion. These agitated passages led the narrative back into the melancholy aura from which they emerged.

Berceuse in D-Flat Major Op. 57 (1844)

This work can surely be considered ‘music of the evening and the night’. The Chopin Berceuse is possibly the most beautiful lullaby in absolute music ever written. The manuscript of this cradle-song masterpiece belonged to Chopin's close friend Pauline Viardot, the French mezzo-soprano and composer.

Perhaps this innocent, delicate and tender music was inspired by his concern with her infant daughter Louisette. George Sand wrote in a letter ‘Chopin adores her and spends his time kissing her on the hands’ Perhaps the baby caused Chopin to become nostalgic for his own family or even reflect on a child of his own that could only ever remain an occupant of his imagination.

Liu's interpretation with her sensitive and musical fingers, contained a poignant tenderness, refinement and poetry replete with the purity of innocence. The work hovers hesitatingly between piano and pianissimo.

The Berceuse, composed and completed at romantic Nohant in 1844, appears to constitute a distant echo of a song that Chopin’s mother sang to him: the romance of Laura and Philo, ‘Już miesiąc zeszedł, psy się uśpiły’ [The moon now has risen, the dogs are asleep]. (Tomaszewski). In view of this tender genesis of infancy, it is well known Chopin loved children and they loved him.

For me the work does speak of a haunted yearning for his own child, a lullaby performed in his sublimely imaginative mind, isolated and alone. No, not a common feeling about the work and possibly over-interpreted on my part, but what of that ...

Johannes Brahms [1833–1897]

|

| The young romantic Brahms |

Ballades, Op. 10 (1854)

No. 1 in D minor (Andante)

No. 2 in D major (Andante)

No. 3 in B minor (Intermezzo. Allegro)

No. 4 in B major (Andante con moto)

These works were composed by Brahms in his early years - he was merely 21 years old. The Ballades, Op. 10, are lyrical pieces written by Brahms as a young man dedicated to his friend the German conductor, composer and musician Julius Otto Grimm. Their composition signaled in part a poetic, amorous and long-lived affection for the pianist and composer Clara Schumann. She helped Brahms launch his career but failed to respond in a manner he might have adored and achieved emotional fulfillment. Brahms conceived of the genre rather differently from the arguably more famous Chopin Ballades.

Brahms's ballades are arranged in two pairs of two, the members of each pair being in parallel keys. The first ballade in D minor was inspired by a Scottish murder ballad "Edward" found in a collection Stimmen der Völker in ihren Liedern compiled by Johann Gottfried Herder. A mother questions her son about blood on his 'sword' and he finally admits that it is his brother, or his father, whom he has killed.

Liu gave an extraordinary psychological exploration of this work as no other I have ever heard. She once again gave me the uncanny feeling that she had become a medium or savant for Brahms. She expressed in some of these works his most internal, almost feminine romanticism, his thoughts of unrequited romantic and filial love. She clearly performed them as if they were created by a young spirit, mired in the emotional throes of yearning love but collecting himself in the end to continue with an active life.

The highly intellectual musical construction was allied to a moving, evolving, organic, internal emotional landscape. Determination allied to the unreality of dreams. Brahms yet remains beset by memories and romantic aspirations as he was in his mature life. Liu compelled us to listen closely and gave us a quite visionary experience of these familiar early works.

Intermission

Alekander Scriabin [1872–1915]

Sonata in F sharp minor, Op. 23 (1897–1898)

Drammatico

Allegretto

Andante

Presto con fuoco

This sonata was completed in the summer of 1898 on a country estate at Maidanovov, before his period of future financial security as a piano professor at the Moscow Conservatoire. He was an imaginative, excellent teacher ranging in subjects from Bach to contemporary works including his own.

‘This chord should sound like a joyous cry of victory, not a wardrobe toppling over!’

The Third Sonata is a large-scale, four-movement work. Liu certainly gave the work the qualities of a polyphonic symphony of epic proportions in the strength of the harmonic transitions in the first Drammatico movement. 'Heroically assertive' music to use the words of the commentator Simon Nicholls.

Several years after publication Scriabin issued a rather mystical ‘programme’ for each movement (as he was wont to do as a result of his obsession with literature and mystical poetry). Some musical academics have indicated that the writer might not be Scriabin but his second wife, Tatyana Schloezer. However, Scriabin certainly approved of the descriptions:

States of Being:

a) The free, untamed soul passionately throws itself into pain and struggle

b) The soul has found some kind of momentary, illusory peace; tired of suffering, it wishes to forget, to sing and blossom—despite everything. But the light rhythm and fragrant harmonies are but a veil, through which the uneasy, wounded soul shimmers

c) The soul floats on a sea of gentle emotion and melancholy: love, sorrow, indefinite wishes, indefinable thoughts of fragile, vague allure

d) In the uproar of the unfettered elements the soul struggles as if intoxicated. From the depths of Existence arises the mighty voice of the demigod, whose song of victory echoes triumphantly! But, too weak as yet, it fails, before reaching the summit, into the abyss of nothingness.

I found Liu's performance was full of high emotional intensity. Technically her pedaling was a miracle that 'unclouded' the dense writing to reveal the structure and polyphony. The second Allegretto movement replaces the traditional sonata scherzo and trio. The beginning is indicated to be played with soft pedal.

The description of the Andante third movement above is an appropriate description for Liu's approach. Lyrical and divine innocent poetry was expressed here by her in a radiant aureole of sound. The pianist Mark Meichik, a Scriabin pupil who later gave the first performance of the Fifth Sonata, reported that the composer’s playing of this passage sounded ‘as if the left hand melody were accompanied by silvery tinklings or shimmerings’; and when Elena Beckman-Shcherbina played it to the composer, Scriabin called out: ‘Here the stars are singing!’

The ‘uproar of the elements’ or tumult and turmoil of the Presto con fuoco finale was created by Liu in a relentless left-hand figuration and troubled chromaticism. I was reminded of the chromaticism of Wagner in Tristan, even Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht written shortly after. In this final movement Liu became truly symphonic and orchestral in the power she produced from the instrument. A tremendous performance with a close in a mood of representative Scriabinesque intransigence.

César Franck [1822–1890]

Prelude, Chorale and Fugue, FWV 21 (1884)

This Franck work was well described by the writer and music critic Adrian Corleonis as ‘an elaborately figured, chromatically inflected, and texturally rich essay in which doubt and faith, darkness and light, oscillate until a final ecstatic resolution.’

After hearing a piece by Emmanuel Chabrier in April 1880, the Dix pièces pittoresques, Franck observed 'We have just heard something quite extraordinary -- music which links our era with that of Couperin and Rameau.' The forms Prélude, Choral and Fugue here are clearly symbolic of their Bach inspired counterparts. The motives are obviously related to the Bach Cantata 'Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen', and also the 'Crucifixus' from the B minor Mass. César Franck transforms these with his own unique solutions and cyclical form.

The influence of the organ and his many years composing sacred texts are obvious here. The pianist Stephen Hough in a note remarked "Alfred Cortot described the Fugue in the context of the whole work as 'emanating from a psychological necessity rather than from a principle of musical composition' (La musique française de piano; PUF, 1930)." The work was finally premiered in January 1885.

Kate Liu gave a magnificent, powerful and authoritative performances of this work. She transported me into the opulent sound world of the organ effortlessly on the Steinway. She managed to extract a full, all stops out, opulent organ timbre, texture and density from the piano as well as great delicacy when required. An appropriately noble and grand atmosphere roused deep spiritual emotions from this secular musical construction.

The nervously agitated toccata-like Prelude had an irresistible rhythmic forward momentum. The emotions of anguish and pain leading to personal redemption were poignantly expressed in the Choral. The work became a spiritual journey from darkness into the light of dawn. Finally in the highly complex and embattled Fugue, suffering is resolved into the triumphant Choral theme once again – like a great chiming of bells.

An instant standing ovation for this rather slight, fey lady who projected us into another world of immortal spiritual consciousness, far from that of our benighted times.

As an encore she played Bach’s chorale “Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit” [God's time is the very best time from the Actus Tragicus] in György Kurtág’s arrangement. To conclude with Bach is just as significant and inevitable as to 'Begin with Bach'

THURSDAY 4.09 5:00 p.m.

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Symphonic concert

CHOUCHANE SIRANOSSIAN violin

TOMASZ RITTER fortepiano

{OH!} ORCHESTR

MARTYNA PASTUSZKA violin

Artistic director

Program

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart [1756–1791]

|

| Portrait of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart at the age of 13 in Verona, 1770 |

Symphony no. 20 in D major, K. 133 (1772)

This symphony was composed in 1772 by the sixteen year-old Mozart.

The Allegro bursts upon us with three

opening energetic notes and then the entrance

of trumpets. Was this some degree of Mozart's notable teenage rebellion against

the dreaded elders? These energetic opening chords and the development are an

exciting new departure for symphonies of the time. In the Andante a charming civilized solo flute often plays

with violins. This elegant, sweet and delicate statement stands out as the focus of the

movement.

Martyna Pastuszka and the {Oh!} Orchestra, although charming in execution of this early Mozart do not overdo the dynamism of the symphony offering us a classical balance tht Mozart had begun to erode. The Menuetto was rather slight and short but maintains a rather conventional forward movement. The Finale Allegro bounds along in contrapuntal spirited style, the texture again lifted by the addition of trumpets. I felt the {Oh!} Orchestra grasped the essential youthful exuberance of this last Salzburg symphony well.

Feliks Janiewicz [1762–1848]

Violin Concerto No. 4 in A major (c.1797)

|

| Chouchane Siranossian |

I traveled to Edinburgh towards the end of June 2022 and among the many adventures and museums visited, I managed to be there for the opening of a remarkable exhibition at the Georgian House. I live in Warsaw in Poland, move in musical circles there, but had never encountered this artist. I was astounded at the discovery.

[The anglicized spelling of his name and surname that he favoured in Edinburgh begins with 'Y' (Felix Yaniewicz) rather than the Polish 'J' (Feliks Janiewicz)]

I met and had a long instructive conversation with the exhibition curator Josie Dixon. She assembled and wrote an excellent article on Felix Yaniewicz, her ancestor and a Polish virtuoso violinist, composer and businessman who was the catalyzing founding force behind the present, world-renowned, Edinburgh Festival. But this was in 1815!

Mozart admired Janiewicz greatly. In fact, Mozart’s 19th-century biographer Otto Jahn speculates that his lost Andante in A major K470 written at this time may have been composed for Janiewicz.

Michael Kelly, a famous tenor, wrote that while in Vienna he was privileged to hear one of the foremost violinists in the world: ‘...a very young man, in the service of the King of Poland, he touched the instrument with thrilling effect, and was an excellent leader of an orchestra. His concertos always finished with some pretty Polonaise air; his variations were truly beautiful.’

I felt the opening Moderato movement to be reminiscent of Mozart although there was not an overwhelming melodic line. I felt Siranossian brought a seductive charm and elegance to this affecting music. The virtuosity that Janiewicz wished to display and Paganini commented upon was clear in this movement and a tribute to the command of the instrument by Siranossian. On occasion I felt he gave an East European or almost Jewish flavour to the violin writing which carried strong contemporary associations here in Warsaw.

Siranossian gave a poignant, singing line in the Adagio movement. She featured a yearning charm that never became mawkish or overly sentimental. Janiewicz's writing for the instrument is emotionally eloquent which she utilized to the full to transfix the audience.

The final Rondo. Allegretto was a dance full of great love and joy! No philosophical torture here ! I have yet to trace the origins of this catchy, simple and mercurially foot-tapping peasant tune. The orchestra under Pastuszka were never tempted to dominate the truly virtuoso violin part, preventing it from shining glitteringly as it certainly would have done originally to the point of shock and did tonight. A beautiful dynamic balance was managed and maintained between soloist and orchestra. The transition to the minor key as the work closed was affecting to the sentiments of the heart.

As an encore Siranossian played a rousing, dancing part of the final movement of the Janiewicz 5th concerto known as klezmer which brought back fond memories of their 2023 performance.

For more on the remarkable Polish virtuoso violinist Feliks Janiewicz and his long period in Edinburgh musical life planting the seeds of the Edinburgh Festival today - if you have time, here is an illustrated presentation ....

http://www.michael-moran.com/2022/09/felix-yaniewicz-music-and-migration-in_7.html

Ludwig van Beethoven [1770–1827]

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 (1798)

Allegro con brio

Largo

Rondo. Allegro

'I

have a real aversion to all out piano concertos (...Beethoven's are not so much

concerts as symphonies with obbligato piano)' This description by

E.T.A. Hoffmann does encapsulate the essential nature of Beethoven's concertos.

This concerto in C major asserts pressure on the formal pattern of Mozart concertos. The silent tutti introduction to the first movement Allegro con brio contains rather powerful themes. Then Ritter and the orchestra unleashed quite an amount of period energy, wit and emphasis. He presented Beethoven as a rebellious youth wishing to break the bounds of Beethoven's model Mozart. I noticed immediately a rare, attractive dynamic balance between soloist and orchestra which persisted throughout. This is a rare occurrence in my experience. Ritter tended to rush a little on the 1849 Erard but the long, substantial cadenza (some phrases possibly improvised) was excellent for this movement and an admirable period addition.

Ritter 'sang' the Largo song in a majestic cantabile and

achieved a substantial musical stature and proportions for the long and majestic movement. This affecting 'song' was

accompanied by the gentlest of strings. The principal clarinet was particularly

eloquent against gentle piano trills and accompaniment sections.

The Rondo. Allegro burst upon us with terrific energy from a virtuosic Ritter

and the orchestra. An infectious sense of dance rhythm and high spirits filled

the hall. At the end of this finale the tempo slowed for a small cadenza, answered

by a poignant solo oboe in Adagio tempo. The contained energy

was then precipitously released by the full orchestra in its original tempo toward the

concerto’s culminating chords. The audience were quite overwhelmed by the expression of this

triumph of the spirit and went wild with applause and shouts of approbation.

A highly enjoyable and unique concert and the triumph of a rather unknown violin concerto, period performance, conducting, orchestration and the Erard piano.

WEDNESDAY 3.09 7:00 p.m.

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Piano recital

ERIC LU

Program

Fryderyk Chopin [1810–1849]

|

| A reproduction of a fragment of a picture depicting Chopin painted by Ludomir Sleńdziński (1951?) |

Polonaise-Fantasy in A flat major, Op. 61

The Polonaise-Fantaisie contains

all the troubled emotion and desire for strength in the face of the multiple

adversities that beset the composer at this late stage in his life. This work,

the first in the so-called ‘late style’ of the composer, was written during a

period of great suffering and unhappiness. He laboured over its

composition. What emerged is one of his most complex of his works both

pianistically and emotionally.

Eric Lu gave us a

thoughtful. analytical performance of this mature Chopin work in many ways. I

could not help reflecting, however, that further analysis of the varied emotional

landscape would have been beneficial.

Chopin produced many

sketches for the Polonaise-Fantaisie and wrestled with the

title. He wrote: ‘I’d like to finish something that I don’t yet know

what to call’. This uncertainty surely indicates he was embarking on a

journey of compositional exploration along untrodden paths. Even Bartok one

hundred years later was shocked at its revolutionary nature. The work is an

extraordinary mélange of genres and styles in a type of inspired improvisation

that yet maintains a magical absolute musical coherence and logic.

Chopin leads us through a

succession of extraordinary scenes and events. I felt Lu could have made the

fantasy element of the work more prominent so that we received a more spontaneous

'searching' improvisational survey of the composition which clearly offered

Chopin many psychological obstacles. They pass in successive train through the

imagination of any listener or pianist who can selflessly give himself in a

meditative trance to this hypnotic music, the composition flickering on the

screen of the mind. I feel one has an imaginative experience bordering on the

cinematic.

Chopin completed it in

August 1846. The reception was one of confusion and even upset. As Jachimecki

stated: ‘the piano speaks here in a language not previously

known’. Frederick Niecks’s judgment was that the

Polonaise-Fantasy ‘stands, on account of its pathological contents,

outside the sphere of art’.

The work reminds me

incontrovertibly of lines from Byron's poem of 1816

The Dream

A change

came o’er the spirit of my dream

The

Wanderer was alone as heretofore,

The

beings which surrounded him were gone,

Or were

at war with him; he was a mark

For

blight and desolation, compass’d round

With Hatred

and Contention; Pain was mix’d

In all

which was served up to him, until,

Like to

the Pontic monarch of old days,

He fed on

poisons, and they had no power,

But were

a kind of nutriment; he lived

And made

him friends of mountains: with the stars

And the quick

Spirit of the Universe

(excerpt)

Piano Sonata in B flat minor, Op. 35 (1839)

The Sonata in B flat

minor, Op. 35, composed in the summer of 1839 at Nohant, was published in

Paris and Leipzig in the spring of the following year. It was not given a

dedication. Personal experiences were transformed into the music which arose

and grew organically around a Funeral March, possibly originally inspired by

patriotic sentiment. The sonata was written in the atmosphere of a blooming sensual

passion frozen by the reality of death as an internal monologue conversation concerning

the nature of existence. The great Polish musicologist Tomaszewski

describes the opening movement of this sonata Grave. Doppio movimento perceptively:

‘The Sonata was

written in the atmosphere of a passion newly manifest, but frozen by the threat

of death.’ A deep existential dilemma for Chopin speaks from these

pages written in Nohant in 1839. The pianist, like all of us, must go one

dimension deeper to plumb the terrifying abyss that this sonata opens

at our feet.

Grave-doppio

movimento

I felt Lu could have

executed the opening four chords of the Grave

in a more measured way, melancholic from the beginning. The opening

is not an announcement but the creation of a funereal atmosphere. One felt it

was the prelude of a disturbed mind facing the reality of death. One hears in them

tragedy, menace, gnawing questions and oracular judgment. These words have been

used by monographers to describe these opening bars of the B flat minor Sonata,

all too often passed over cursorily by young pianists, understandably inexperienced

with life's darker inevitabilities. Such language recognizes they contain the

kernal of tragedy. What follows is a powerful premonition.

Lu unfolded the doppio movimento like a restless narrative ballade. A feeling of propulsion evoked a galloping horse. Chopin himself was reputed to be an indifferent horseman, an ability of immense importance for any nineteenth century gentleman. One should reflect after this comment that movement during Chopin’s time was restricted either to walking, horse or carriage. So when a composer wished to impart movement to a piece of music he could not envisage all of the extraordinary modes of travel we have at hand. The urgency and ominous passage of a rider, occasionally even in a reflective even nostalgic mood, yet galloping inexorably towards his doom. I still felt a certain classical restraint of emotion which is so important to this work.

I felt Lu could have made the contrasting 'song' within this movement warmer and more lyrical, even embracing moments of ecstasy.

The first movement

of the sonata concludes with a series of chords played fff. One

must remember on an immense modern Steinway, this conclusion will be of gargantuan

and exaggerated dimensions played at that dynamic. One must consider Chopin's

dynamic markings should be performed at one dynamic step lower for his Pleyel

than in our modern, inflated sound world. His indications in the music interpreted literally

on a modern instrument, often distort the reception and the emotional impact and

meaning of his specified dynamic.

The doppio

movimento contains within it immense dark thoughts and żal, confronting

us with our demise. żal, an untranslatable Polish word in this

context, meaning melancholic regret leading to a mixture of passionate

resistance, resentment and anger in the face of unavoidable fate. Lu hastened

along here, occupied in his musical imagination with a moderate yet horrified

contemplation that was atmospheric in its contrast of dreams and grim reality -

much the way life presents itself.

Scherzo

the tortuous tension

is maintained in the Scherzo. 'In the midst of life we are in death' emerged

as an undiminished sentiment, a message only temporarily assuaged by the lyric

and poetic contrasting nature of the trio which emerges from silence. The

Polish musicologist Zdzisław Jachimecki sees ‘demonic features’ in it. And

indeed, according to Tomaszewski, one might say that it combines Beethovenian

vigour with the wildness of Goya’s Caprichos.

Concerning the metaphysical

possibilities for Chopin, he wrote to Solange Dudevant (1828 – 1899),

the daughter of George Sand, from Scotland (Johnston Castle) on 9

September 1848:

‘When I was playing my Sonata in B flat minoramidst a circle of English friends, an unusual experience befellme. I executed the allegro and scherzo more or less correctly [Chopin was always self-critical] and was just about to start the [funeral] march, when suddenly I saw emerging from the half-opened case of the piano the cursed apparitions that had appeared to me one evening in the Chartreuse [on Majorca]. I had to go out for a moment to collect myself, after which, without a word, I played on’.

George Sand confirms in her Majorcan memoirs Chopin’s neurotic and unstable imagination.

Marche funébre

A properly eloquent tempo and dynamic for the Marche funèbre is difficult to achieve. So many people seem to think it ought to accompany an imaginary military band with a heavy dull tread lacking in poetry. However pall bearers in a cemetery move and sway with the heavy bier rather in slow motion. I felt as always the tragic inevitability of death for all of us, a deep and haunting melancholy, an almost childish innocence within the cantabile nocturnal central section, a forlorn cry of the soul facing its inevitable destiny.

Lu gave particularly

pregnant silences between movements which gave time for reflection to fully

absorb the dark emotions and implications about to be unfolded in the Marche

funébre.

His deliberate tempo gave immense existential weight to the utterance, avoiding the customary inflated dynamics for crude, operatic effects. The lyrical cantabile possessed a feeling of the desperate reality of memory of the departed and dreams of what might have been. However, I felt a need for even more poetic contemplation of the grey and mysterious realities of death but this may be indicative of my own febrile imagination. Chopin was terrified of being buried alive – often horrifyingly possible in those primitive medical times.

Finale. Presto

I feel this movement more as a frantic, hysterical but submerged and sublimated panic of the mind, the disorientated mental reaction one feels as a sensitive human in the mysterious face of death. 'Wind over the graves' is far too prosaic an interpretation. More a musical stream of consciousness expressed in baroque counterpoint of superb virtuosity. Lu convincingly presented it in this hectic counterpoint manner.

The extreme succinctness of the B flat minor Sonata suggested a comparison to the great Polish composer Witold Lutosławski - ‘it’s like a sculpture hewn from rock’ rather than four unruly children as Schumann perceived it.

Intermission

Polonaise in B flat major, Op. 71 No. 2 (1828)

This rarely performed work, written in 1828, rests on the cusp of change. It shows Chopin beginning to introduce personal moods and emotions into his work and move away from conventional expressions in the shackles of previous forms and genres. The shadows of Polish nationalism hover over the work even suffusing its charming melody.

This Polonaise seems to be one of the documents of an imminent breakthrough. It was composed in the virtuosic style brillante. Really it is a piece of chamber music for an intimate room. As Frederick Niecks noted, in Chopin’s music from that time ‘The bravura character is still prominent, but, instead of ruling supreme, it becomes in every successive work more and more subordinate to thought and emotion’. This work admirably reconciles the conventional with the original, the coquetry of the salons with the approaching Romantic watershed (Tomaszewski)

Lu gave an excellent account of the style brillante work even if lacking slightly in finesse, deep sense of the nature of the polonaise rhythm and the rather Polish ‘classical’ polonaise genre.

Piano Sonata in B minor, Op. 58 (1844)

This sonata is one of the

greatest masterpieces in the canon of Western piano music. I had

heard Lu perform this sonata not long before at the Duszniki Zdrój Chopin festival. As interpretations

labored and thought over for years by pianists, lifetimes in some cases, I see

no reason to completely review his interpretation in a few varied details once again.

Lu opened the sonata

dramatically and polyphonically but with immense clarity and controlled power

which is a hallmark of his execution at the keyboard. The opening Allegro

maestoso was dramatic but revealed poetry and moving lyricism.

One should feel here that

Chopin was embracing the cusp of Romanticism, yet at the same time hearkening

back to classical restraint - le climat de Chopin as his

favourite pupil Marcelina Czartoryska described it. The Trio did have a

beautiful legato cantabile that made the piano sing.

The Scherzo revealed

all the glistening articulation Lu was capable of, being energetic with a

Mendelssohnian atmosphere of Queen Mab fairy lightness. The Trio again

displayed a warm Chopin cantabile.

The transition to the Largo was

not sufficiently expressive and Lu was rather heavy for my conception of this profound moment. Here, however, we began with him an exquisite extended

nocturne-like musical voyage taken through a night of meditation and

introspective thought. This great musical narrative, an emotional landscape we

travelled through, an extended and challenging harmonic structure, was

presented as a poem of the reflective heart and spirit. I felt his playing was

tonally refined and transported us with spiritual introspection, enveloping us

in a mellifluous dream world.

The Finale. Presto

ma non tanto was certainly a tremendously powerful expression in

its headlong flight though the threats and obstacles that life heartlessly

throws up before us. He approached this movement with tremendous virtuosity

which benefits its emotional impact, not unlike a rhapsodic narrative Ballade in

character. Again Tomaszewski cannot be bettered:

Thereafter, in a constant Presto (ma non troppo) tempo and with the expression of emotional perturbation (agitato), this frenzied, electrifying music, inspired (perhaps) by the finale of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony…’

As encores two Chopin waltzes - The C sharp minor Op.64. No.2 and the A-flat major Op.42

Eric Lu appears courtesy of Warner Classics

Part II

TUESDAY 2.09 7:00 p.m

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hal

Piano recital

YULIANNA AVDEEVA

I found both parts of this recital magnificent and astounding in parts. I cannot go into an analysis of each Prelude & Fugue here, but I will make some general observations. A number were gentle-toned, rather introverted and alluringly Chopinesque works. Others contained dark, premonitory openings which were not ambiguous, knowing the history of Russia at that time and the attitude to 'culture'. Tragedy and introverted yet expressive harmonies.

Avdeeva has an immense range of articulation, dynamic variation and rhythmic control. Her fugues seemed to contain the energy of the cosmos and were quite fantastic in dynamic impact. The timbre, colours and texture she was able to almost suffocate my diatonic, harmonic musicality and take my breath away. I was aware of the ringing of Orthodox bells in certain works.

Impressionistic waves of sound brought me to the shores of a great ocean, moving in abstract arabesques. Dramatic hammer blows put me in mind of the Russian proverb: 'The heavy hammer forges strong steel but breaks fine glass.' Black dynamism and destruction alternated with ethereal ppp (ultra pianissimo) bliss.

The historically reminiscent polyphony that recalled Bach was always clear and transparent despite the incredibly powerful musical imagination of Shostakovitch and the mercurial execution by Avdeeva. Hell and Elysium. The Sacred and Profane in life. The close of the recital was a triumphant assertion of creative life with visionary rubato, phrasing, breathing and tremendous dynamics.

Almost instant standing ovation and wild cheering.

|

| A deeply moved member of the audience following this magnificent recital |

Her Encore was the riveting Prelude & Fugue in C-sharp minor by Shostakovitch.

- Manufacturer : Pentatone

- Label : Pentatone

- ASIN : B08DCWMPVZ

- Country of origin : Germany

- Number of discs : 2

Program Part II