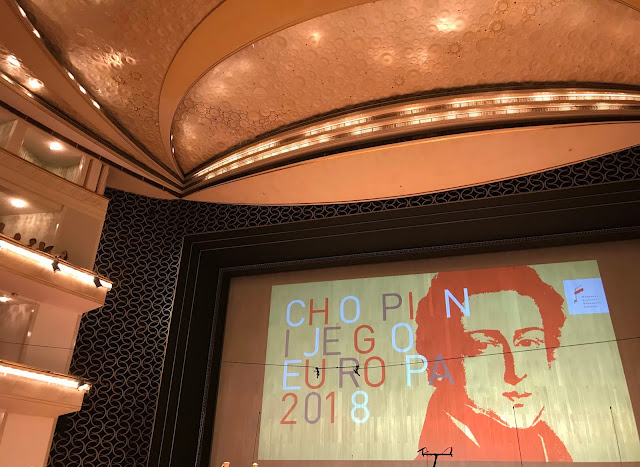

14th Chopin and his Europe (Chopin i jego Europa) International Music Festival Warsaw 9-31 August 2018

From Chopin to Paderewski

The Polish Rhapsody is not a complex work begins calmly on the cor anglais which gives way to a military march as we move into the spirit of the piece which must be encapsulated by the word 'resistance' - actually if there was one word to describe Poles and Polish history this would be it - resistance. Out of the march inevitably grows the 'Dąbrowski Mazurka' (the present Polish national anthem). The work concludes in a folk idiom. This work was very popular after the war in the US bu not so often performed these days.

After the interval, the brilliant young English pianist Benjamin Grosvenor was to play Chopin's Piano Concerto in F minor (1829-30) Op. 21. To conclude the concert and the festival, probably what everyone was waiting for, the Chopin Piano Concerto in F minor Op.21.

The work itself was written 1829-30. as we all know by now, this concerto was inspired by Chopin’s infatuation or was it youthful love for the soprano Konstancja Gładkowska. Strangely it was published a few years later with a dedication to Delfina Potocka.

Grosvenor was confident, relaxed, enjoying his playing immensely. He had excellent communication with Kaspszyk, the conductor of the Warsaw Philharmonic. He retained a natural virtuosity that preserved the form and was always a servant to the conception and interpretation.

And so we came to the end of a most brilliant festival lasting a quite remarkable three weeks. During this time I came to know so much about forgotten or seldom performed Polish music and was made aware of some fertile Polish tributaries I shall certainly follow up on with undoubted musical rewards promised at the end.

I was immediately struck by the superb ensemble tone and balance from the opening notes of the rather sombre Adagio ma non troppo that opens the work. Later the movement became playful, meditative and joyful in turn - many changes of mood and tempo. Throughout there was total emotional, even physical commitment to the music of the performance or rather more accurately, the recreation of the work. What a lesson for other musicians who are too often merely going through 'reproductive' emotions! There was galvanic creative energy present here this evening.

After the interval the quartet were joined by the legendary pianist Elizabeth Leonskaya to perform the Brahms Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 (1864) One of my favourite quintets, a youthful Brahms work, had a difficult gestation and birth in various transformations as a string quintet, sonata for two pianos until coming to fruition in its present form in 1864. Almost a symphony. The straightforward lyricism and energy of assertion in life's pleasures and confident youth could not have been in greater contrast to the preceding somewhat tortuous and fraught Beethoven quartet. The Allegro non troppo began with such grave nobility and strength and in the piano part developing magnificently with Leonskaya seemingly possessed by an inner force of nature, giving absolute maximum musical intensity to the work. As did the Belcea quartet as they charted the rising temperature of the passions. Truly magnificent to hear and behold.

26.08

SUNDAY 6.00 p.m.

PADEREWSKI DAY

25.08 SATURDAY 9.00 p.m.

25.08 SATURDAY 5.00 p.m.

In many ways it is a great shame I have experienced the opera HALKA only in the concert version however distinguished the orchestra and soloists. The Warsaw première of the opera Halka by Stanisław Moniuszko on 1 January 1858 with a intensely poetic and pantheistic libretto by Włodzimierz Wolski was a fulchrum in the history of Polish music. The original libretto was also translated into Italian but never performed in that language. It was the first Polish national opera.

From the moment of its Warsaw première in 1858, general interest in Moniuszko’s opera continued to grow. In June 1860 Warsaw daily press informed readers: 'A request for the score of Halka has been received from Prague'. Moniuszko visited Paris twice, the opera capital of Europe. Promotion of his work in the French capital proved fruitless. Some associate the composition of the opera and the lot of heroic yet betrayed peasant class (Halka) and a mendacious class of nobility (Janusz) with the turbulent peasant revolt events of the Kraków Uprising of February 1846. It has been performed well over a thousand times in Warsaw.

Then to the rarely performed Benjamin Britten [1913–1976] Piano Concerto, Op. 13 (1938). One must consider two aspects in its gestation and composition. First the age of the twenty-five year old, who like all young men of ambition, was intent on building a career as a pianist and composer. Always suffering from stage fright, he feared appearing as the soloist when the work was premiered at a Prom concert in the summer of 1938 under the baton of Sir Henry Wood. Following the rehearsal he wrote to his publisher:

The audience were positive as were the reviews, although the first two movements considered stronger than the two following. ‘If music be indeed the food of love, I think you stand a very good chance’, commented Lennox Berkeley to whom he dedicated the work. The orchestral writing was extraordinarily brilliant. From the musical point of view Britten wrote in the program note:

After the interval the Symphony No. 2 in D major Op. 43 (1901-2) by Jean Sibelius [1865–1957]. The composer said of it: 'My second symphony is a confession of the soul.' There is some controversy over whether this is a nationalist work as at the time of composition Finnish language and culture were proscribed by the Russians. Sir Colin Davis quoted the English poet William Wordsworth for one of his recordings of the symphony with the London Symphony Orchestra:

Edward Gardner (immensely communicative, intensely physically active and charismatic) with the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra brought magnificent ensemble to this profound, demanding and unconventional work. Sibelius certainly had grandiose ideas concerning its form: 'It is as if the Almighty had thrown down the pieces of a mosaic for heaven’s floor and asked me to put them together.' The first movement Allegretto opens in 'heavenly pieces' with many tempo indications that only cohere after some time. The second movement Allegretto. Tempo andante ma rubato unusually opens with a timpani roll. Slowly the volume, tempo and pitch rise to a fortissimo in the brass (powerful and strident in this orchestra) followed by a sudden and dramatic contrast of a tender theme on the violin played pianissimo.

I found the emotional tension and sheer volume of opulent sound that Edward Gardner constructed with the Bergen Philharmonic transcendentally overwhelming. A musical experience of the first water.

23.08 THURSDAY 5.00 p.m.

One of the most attractive aspects of this festival are the concerts devoted to musician friends and acquaintances of Fryderyk Chopin whose former fame and lustre has faded somewhat as time passes. This concert was devoted to the French composer and cellist Auguste Franchomme (1808-1884) whom Chopin met and befriended in Paris in the early 1830s. He dedicated a number of works to the cellist, including the great cello sonata and at times performed with him. Franchomme was also a close friend of Felix Mendelssohn. He was an illustrious figure in the musical life of Paris and pioneered revolutionary bowing techniques for his instrument and precision techniques in left-hand playing.

For me a glorious change of mood from this sombre beginning. The orchestra was joined by Jan Lisiecki for Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto in G minor, Op. 25. Of Mendelssohn as a pianist Clara Schumann once wrote to Robert 'For a few minutes I really could not restrain my tears. When all is said and done, he remains for me the dearest pianist of all.' It is all to easy to forget that Mendelssohn was celebrated as a pianist as well as composer - something we have not forgotten concerning Chopin and Liszt. Mendelssohn was only 22 (much the same age as Lisiecki) when he completed this concerto in 1830-1 and undoubtedly full of boundless creative and youthful energy. Alfred Einstein wrote so appropriately of his music: 'He had no inner forces to curb, for real conflict was lacking in his life as in his art.....But his instrumental and vocal works are alike masterpieces of refinement, clarity and control.'

Matters begin rather precipitately with a dramatic gesture in this concerto. There is no long orchestral tutti introduction as in a Classical concerto before the piano enters - the entry is combined. For this reason I felt it could have had more explosive 'fire' at the beginning. Lisiecki took the Molto allegro con fuoco at such an exciting cracking tempo with quite brilliant articulation and forward drive it precluded any injection of great expressive charm which the movement needs if it is to escape the charge of superficial facility and lightness. 'He [Mendelssohn] played the piano as a lark soars...' wrote Ferdinand Hiller. If one watches birds they dip and glide in the currents of air in artistic arabesques. On the other hand the Andante was most affecting in its expressiveness with a truly glorious tone. A true 'Song Without Words'. I could not help but reflect on the emotional maturity this pianist has gained since I last heard him some time ago now. Without a break the Presto – Molto allegro vivace. Lisiecki launched into the diverting 'tune' of this movement with boundless youthful energy that carried all my reservations before it. Also he was playing splendidly without a conductor to assist him through difficult orchestral and solo synchronizations.

After the interval the Mendelssohn Piano Concerto in D minor Op. 40 (1837). I am privileged to allow Schumann to speak for me. 'It is as though a tree had been shaken, and the ripe, sweet fruit had promptly fallen.' The Second Concerto resembles the first in structure and texture but I felt Lisiecki was far more accomplished expressively in this work. The Allegro appassionato had far more 'air' to the phrasing and we were given time to follow the charming modulations and relatively undemanding keyboard writing. Again I thought of the heartfelt and affecting cantilena in the Adagio: Molto sostenuto replete with moving introspective expressiveness and beautiful tone colour. Perhaps the composition reflected both the tragedy of Mendessohn's father's death and his joyful honeymoon that followed so soon after. Then to the Finale. Presto scherzando. This movement is so happiness inducing I have nothing but praise for this young man in raising my spirits with his airy, light articulation and dotted rhythmic momentum.

Listening to the Allegro vivace, it was as if the ghost of Mendelssohn's Midsummer Night's Dream music was hovering over it. This musical and textural presence remained through all the movements. The triplet dance rhythm is reminiscent of and evokes the pleasures of the Roman carnival. 'Pleasure' is the predominant mood this orchestra maintained throughout.The tightness and unison of this chamber ensemble was truly to marvel at while the revelation of internal detail of the score was quite wonderful. The string pianissimos were ravishing and absolutely to die for. The transparent combination of flutes and violins in the Andante con moto was refined and elegant. A poetic, restrained and tasteful Con moto moderato then ensued.

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

I had been anticipating this recital for some time having heard this musically inspiring duo at Duszniki Zdrój and of course the consummate pianist many times in solo recital. The programme design overall and the thematic thinking behind it - Paderewski, Debussy, Beethoven and Resphigi - was difficult to fathom.

The Allegro vivo possessed great sensuality with its significant mood swings. The tremendous, even passionate commitment on the part of both violinist and pianist was clear. The Intermède. Fantasque et léger was lyrical and tender, glorious in violin tone, then suddenly interrupted with capricious flights of fancy. Baeva was simply fabulous in ravishing colour, attack and the expression of its fractured emotional communication. The Finale. Très animé built to an ecstatic conclusion, even optimism, so surprising in view of Debussy's tragic circumstances approaching death, for all of us, far too fast. I felt an Hungarian flavour to the composition here. Kholodenko provided superb impressionistic support on the piano. The composer died not long after the premiere by himself on 25th March 1918 at the tragically young age of 58. Such a valedictory statement from Debussy as the lights were slowly extinguished. 'Rage, rage against the dying of the light.' as the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas may have put it.

François-Joseph Gossec [1734–1829] was tremendously engaged politically and was commissioned to write music for The Revolution. We heard the most engaging Offrande à la Liberté ou ‘La Marseillaise’ in C major (1792) performed at the Opera on 30 September of the First Year of the Republic. We heard a stirring instrumental version of the work minus the original Chorus. The music was in quite the 'military march genre' and not so musically distinguished yet I found it stirring all the same. It is hard to avoid such psychologically programmed responses to national hymns!

After the interval the Johann Wilhelm Wilms [1772–1847] Variations in D major on ‘Wilhelmus van Nassauwe’, Op. 37 (pub. 1814). This work is the national anthem of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. this Dutch composer wrote what was the unofficial anthem from 1815-1932 and the variations on the song. I found this an unimpressive, rather innocuous piece of music.

The concert opened with Józef

Elsner [1769–1854] Overture to the Opera Leszek

Biały [Leszek the White] (1809). Interestingly a performance of this opera

fired up national fervour in Poland among the local population for 'Polish

music!' which great alarmed the Russian authorities (ironically similar to today's

mood that worries no-one). The performance of the Orkiestra Historyczna under their conductor VÁCLAV LUKS was as passionately patriotic as the

music and put me in mind that Chopin's teacher Elsner was not some little old

grey piano teacher in a dilapidated Warsaw tenement but a pre-Verdian composer

of great distinction who founded the Warsaw Conservatoire.

13.08 MONDAY 8.00 p.m. Polish National Opera Symphonic concert

31.08 FRIDAY

8.00 p.m.

Moniuszko

Auditorium at the Teatr Wielki – Polish National Opera

Symphonic

concert

YAARA TAL piano

BENJAMIN

GROSVENOR piano

WARSAW

PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

JACEK KASPSZYK conductor

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński and D. Golik/NIFC]

A chance to 'discover' another work by the once famous Polish composer, Aleksander Tansman (1897-1986), once considered as important as Szymanowski. The magnificent violin concerto we heard earlier in the festival cemented him in my mind as an outstanding composer inexplicably rather overlooked in the West at least by popular opinion. The cultural iron curtain perhaps operating as a psychological and prejudicial barrier once again. Tansman was a distinguished Polish composer born in Łódz and a virtuoso pianist. After further studies in Warsaw he moved to Paris where his less than conservative composing style was appreciated by Stravinsky and Ravel. He also had a highly successful concert career as a pianist in France. He was even 'encouraged' to become the seventh member of Les Six.

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński and D. Golik/NIFC]

A chance to 'discover' another work by the once famous Polish composer, Aleksander Tansman (1897-1986), once considered as important as Szymanowski. The magnificent violin concerto we heard earlier in the festival cemented him in my mind as an outstanding composer inexplicably rather overlooked in the West at least by popular opinion. The cultural iron curtain perhaps operating as a psychological and prejudicial barrier once again. Tansman was a distinguished Polish composer born in Łódz and a virtuoso pianist. After further studies in Warsaw he moved to Paris where his less than conservative composing style was appreciated by Stravinsky and Ravel. He also had a highly successful concert career as a pianist in France. He was even 'encouraged' to become the seventh member of Les Six.

Darius Milhaud wrote of Les Six:

'Collet [French critic Henri Collet] chose six names absolutely arbitrarily, those of Auric, Durey,

Honegger, Poulenc, Tailleferre and me, simply because we knew each other and we

were pals and appeared on the same musical programmes, no matter if our

temperaments and personalities weren't at all the same! Auric and Poulenc

followed ideas of Cocteau, Honegger followed German Romanticism, and myself,

Mediterranean lyricism!'

Tansman the Pole of Jewish extraction would have been at home in this

company.

In 1940 he composed tonight's piece, the popular Polish Rhapsody, dedicated to the heroic defenders of Warsaw in the

ill-fated Rising who were defeated by the Nazis. In 1941, being Jewish, he

fled Europe to Los Angeles where he composed many remarkable film scores. After

the war he returned to Europe to produce some outstandingly brilliant compositions

performed by many of the greatest instrumentalists, conductors and orchestras.

|

| Jacek Kaspszyk conducting the Warsaw Philharmonic in the Polish Rhapsody |

The Polish Rhapsody is not a complex work begins calmly on the cor anglais which gives way to a military march as we move into the spirit of the piece which must be encapsulated by the word 'resistance' - actually if there was one word to describe Poles and Polish history this would be it - resistance. Out of the march inevitably grows the 'Dąbrowski Mazurka' (the present Polish national anthem). The work concludes in a folk idiom. This work was very popular after the war in the US bu not so often performed these days.

This was followed by yet another composer I knew even less about,

Karol Rathouse [1895–1954] and his Piano Concerto Op. 45 (1939) in three movements

- Moderato; Andantino; Allegretto con

molto; and was performed by the Israeli pianist Yaara Tal. Rathouse was another Jewish

composer and musician whose life was effectively shattered at the peak of its

creative promise by Hitler's rise to power. This work is one of radical

modernism, a genre of music verging on atonality that caused a symphonic scandal

in Vienna. Yet in Berlin he was in demand for film music. However his career

had been interrupted profoundly. He fled to Paris in 1932 intuiting the

inevitable. From 1941 until his death, in 1954, Rathaus was a professor of

music at Queens College.

The piano concerto seemed in its percussiveness and general neo-Romantic

mood to remind me of Bartok and then in its more lyrical moments of Berg. There

is an ominous atmosphere that pervades this composition. Despite the brilliance

of the pianist I found the work possibly profound in its premonitory horror of

the 1940s but inaccessible in any deep emotional sense to me in 2018.

|

| Yaara Tal in the Karol Rathaus Piano Concerto Op.45 |

After the interval, the brilliant young English pianist Benjamin Grosvenor was to play Chopin's Piano Concerto in F minor (1829-30) Op. 21. To conclude the concert and the festival, probably what everyone was waiting for, the Chopin Piano Concerto in F minor Op.21.

‘As I already have, perhaps unfortunately, my ideal, whom I

faithfully serve, without having spoken to her for half a year already, of whom

I dream, in remembrance of whom was created the adagio of my concerto’ (Chopin

to his friend Tytus Woyciechowski ,3 October 1829).

The work itself was written 1829-30. as we all know by now, this concerto was inspired by Chopin’s infatuation or was it youthful love for the soprano Konstancja Gładkowska. Strangely it was published a few years later with a dedication to Delfina Potocka.

I have little to say other than praise this fine performance of

the F Minor Concerto Op. 21. At least this English pianist not

treat Chopin as a composer for schoolgirls, all too common in England in the

past. The performance was 'finished' and close to faultless technically

speaking, but the phrasing and breathlessness in the Maestoso, with sometimes a harsh left hand pointing up an important

harmony or emphatic moment was overdone. The concerto followed the Mozart model

and was directly influenced by the style brillant of Hummel,

Kalkbrenner, Moscheles or Ries. It is hard to reproduce this intimate yet

fragile glittering tone on a Steinway or Yamaha but I felt Grosvenor managed this

internally iridescent style well with sparing use of the pedal and mainly

finger legato. Here again Chopin magically transforms the Classical into the

Romantic style.

|

| Benjamin Grosvenor and Jacek Kaspszyk before the performance |

Grosvenor was confident, relaxed, enjoying his playing immensely. He had excellent communication with Kaspszyk, the conductor of the Warsaw Philharmonic. He retained a natural virtuosity that preserved the form and was always a servant to the conception and interpretation.

A singing full bel canto tone in the affecting Larghetto that

was full of poetry but taken slightly too fast for the full poetry of yearning

to emerge convincingly (again personal taste). In many ways you could say

that the whole work revolves around this movement. I always think of the

sentiments contained in the 1820 poem by John Keats La Belle Dame Sans

Merci when I hear this music with its passionate interjections

I met a

lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a

garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan.

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She looked at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan.

I set her

on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

That final forty-note fioritura of longing

played molto con delicatezza always carries me away into

Chopin's dreamy Romantic poetical world.

Tremendous joy, energy and drive in the Rondo Allegro

vivace final movement in the exuberant style of a krakowiak dance.

How Chopin must have loved the bucolic nature of the

Polish countryside and its music! The Chopin extension of the Hummel

piano concerto was here fully realized. Melody and bravura figuration

(F minor to the relative major A flat for instance) wonderfully and

authoritatively brought off with great balance of formal structure.

This composition that lies between Mozart and the styl

brillant was very promisingly executed as were the masculine gestures

towards the concertos of Weber (following the cor de signal for

example). A satisfying performance in almost every way expressing the

dreams and exuberance of youth.

A sweet encore - Rachmaninoff's song Lilacs transcribed for solo piano by the composer.

And so we came to the end of a most brilliant festival lasting a quite remarkable three weeks. During this time I came to know so much about forgotten or seldom performed Polish music and was made aware of some fertile Polish tributaries I shall certainly follow up on with undoubted musical rewards promised at the end.

|

| And so the monumental Chopin i jego Europa Festival for 2018 concludes... |

31.08 FRIDAY

5.00 p.m. Polish National Opera

Chamber concert

ELISABETH

LEONSKAJA piano

BELCEA QUARTET

CORINA BELCEA violin

AXEL SCHACHER violin

KRZYSZTOF

CHORZELSKI viola

ANTOINE

LEDERLIN cello

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

Having heard the Belcea Quartet before in this festival, I consider them to be a wonderfully inspired group of mixed nationalities (the violinist Corina Belcea after which the quartet is named, is an impassioned Romanian artist). Most

recently they performed in Warsaw in August 2016 and 2017 and as a result I was keenly anticipating this concert. The more

so that they would be joined by the great distinguished Russian pianist and musician Elizabeth

Leonskaja.

They opened their concert with the formidable Beethoven String Quartet in B flat major, Op. 130 (1826).

This work obtained the nickname 'Lieb' (Dear) from Beethoven himself,

who referred to it with this name in his writings.

|

| The Belcea Quartet |

I was immediately struck by the superb ensemble tone and balance from the opening notes of the rather sombre Adagio ma non troppo that opens the work. Later the movement became playful, meditative and joyful in turn - many changes of mood and tempo. Throughout there was total emotional, even physical commitment to the music of the performance or rather more accurately, the recreation of the work. What a lesson for other musicians who are too often merely going through 'reproductive' emotions! There was galvanic creative energy present here this evening.

This was the last of three string quartets commissioned in the 1820s

by the Russian Prince Galitzin. According to Barry Cooper the first two

movements did not pose any problem for Beethoven but for quite a length of time

he was undecided about the actual structure

and in terms of how many movements. The finale posed endless changes of

direction. The Belcea brought tremendous energy to the Presto (a theme packed with colour, humour and delight) and in the Andante con moto, ma non troppo rather more vital than the tempo indication.

The Belcea brought a rhythmic and melodic idiomatic understanding to the Alla danza tedesca. Allegro assai (in

the German style). I was amazed at the varied 'attack' these instrumentalists

brought to their bowings - sometimes lyrically legato, superbly detaché, rough

and almost coarse fortissimos when

the context demanded it, rich smooth ensemble when that was expressively

necessary. A case in point was the divine Cavatina.

Adagio molto espressivo. The movement is at once dark, melancholy, intense

yet profound in its emotional resonance. Even the deaf composer admitted to

being moved to tears by this movement, one of the finest things Beethoven ever

wrote. The Belcea did this full range of emotions justice, the pianissimos and phrasing, rather like a curious

halting breath, seeming to me a presage of death. The composer died only months

after finishing the composition.

Originally the Finale was a

monumental fugue but after months of indecisiveness this idea was abandoned for

the last complete piece Beethoven wrote, a Finale.

Allegro The rather happy mood belies the health problems of Beethoven who

was to die only months after finishing the composition. The Belcea brought the

work to a brilliant conclusion before launching passionately into the mighty Grosse Fuge (actually published separately

as Op. 133). This wrought-iron work was absolutely magnificently assembled by

this quartet like a piece of soaring architecture. One can only imagine the

effect such a taxing complex musical design must have had upon contemporary

audiences. For me the Belcea moved into the region of the transcendent in this

monumental and formidable construction. One of the truly great performances of

this quartet which will remain lodged with me.

|

| The Belcea Quartet and Elizabeth Leonskaya |

After the interval the quartet were joined by the legendary pianist Elizabeth Leonskaya to perform the Brahms Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 (1864) One of my favourite quintets, a youthful Brahms work, had a difficult gestation and birth in various transformations as a string quintet, sonata for two pianos until coming to fruition in its present form in 1864. Almost a symphony. The straightforward lyricism and energy of assertion in life's pleasures and confident youth could not have been in greater contrast to the preceding somewhat tortuous and fraught Beethoven quartet. The Allegro non troppo began with such grave nobility and strength and in the piano part developing magnificently with Leonskaya seemingly possessed by an inner force of nature, giving absolute maximum musical intensity to the work. As did the Belcea quartet as they charted the rising temperature of the passions. Truly magnificent to hear and behold.

The Andante, un poco adagio was

at once tender and lyrical. The German-Jewish orchestral conductor Hermann Levi

told Brahms:

The quintet is beautiful beyond measure; no one who didn’t know it in

its earlier forms—string quintet and sonata—would believe that it was conceived

and written for other instruments. Not a single note gives me the impression of

an arrangement: all the ideas have a much more succinct colour. Out of the

monotony of the two pianos a model of tonal beauty has arisen; out of a piano

duo accessible to only a few musicians, a restorative for every music-lover—a

masterpiece of chamber music of a kind of which we have had no other example

since ’28.

Levi was

referring to the death of Schubert in November 1828 - his shade and that of

Beethoven hover over the work. The Scherzo. Allegro in C minor has an

atmosphere of polyphonic drama contained, held back somewhat mysteriously. Belecea

and Leonskaya seemed to me perfectly matched in emotional connections and understanding

during this work. I found the closing movement Finale. Poco sostenuto – Allegro non troppo emotionally overwhelming. Textures were

transparent and inner details abounded. This was not a turgid Brahms of thick

coffee and cigars, but a man of internal fires, vitality and intensity. It was

as if we were being submerged within the crucible of Brahms's creative power. I

am not subject to hyperbole but in this case words truly fail me. The Finale

was worked into a monumental edifice. Instant standing ovation from me and not

normal behaviour - cannot even remember the last one I gave so spontaneously.

As an encore the vivacious cross-rhythmed Scherzo (Furiant): Molto vivace from Antonín Dvořák's Piano Quintet in A major Op. 81

This concert

was a profoundly satisfying musical experience from the Belcea Quartet and

Elizabeth Leonskaya on so many spiritual levels. Unforgettable.

|

| Elizabeth Leonskaya in conversation with the Artistic Director of the Festival Stanisław Leszczyński |

Moniuszko

Auditorium at the Teatr Wielki – Polish National Opera Symphonic concert

ANNA

MARIA STAŚKIEWICZ violin

RUSSIAN

NATIONAL ORCHESTRA

MIKHAIL

PLETNEV conductor

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

At Westminster College on 5 March 1946 Winston Churchill made a speech

that created in the mind a barrier across Europe. The words are well known but

some implications are not fully realized.

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in

the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.

Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and

Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest

and Sofia;

One must always remember that the 'Iron Curtain' was a cultural as

well as political barrier. This meant there was little cultural osmosis across

it in either direction apart from what had already taken place before the war.

This accounts for the ignorance in Western countries of much music from these

Central and Eastern European states which is only now beginning to surface.

Discovering one's politically suffocated historical and cultural heritage is a

deep draught of the heady elixir of freedom.

This is one of the positive excitements of the present in Poland yet one

must guard against distortions of judgment, both positive and negative, that

come from cultural elation.

Although familiar to musically educated Poles, the precocious late

Romantic composer Mieczysław Karłowicz [1876–1909] who died in an avalanche at

the tragically young at the age of 33, is relatively unknown outside the

country. Certainly his work is not sufficiently familiar to me to write in

informed detail about it. His six symphonic poems cause him to be considered Poland's

greatest symphonic composer. At the time opposition to his compositions

was violent. The music historian Aleksander Poliński wrote of young composers

that they '...have now been affected by some evil spirit that depraves their

work, strives to strip it of individual and national originality and turn into

parrots lamely imitating the voices of Wagner and Strauss'. Karłowicz's

compositions were regarded as 'modernistic chaos' which made them unpopular

with the Polish public.

The first work on this program was the Serenade for String Orchestra, Op. 2 (1897) It was composed when

Karłowicz was 21 (studying in Berlin under Heinrich Urban) and consists of four

movements and one of his most frequently performed works: March - Romance - Waltz - Finale. I found it very charming music

that put me in mind of civilized life in Europe before the Great War. The

Russian National Orchestra seemed to me a very large orchestra (7 double basses

par example) for such evidently light

instrumental scoring but it seemed to paint a relatively effective panorama of the

sensibility of the day. Poles at the time I believe were known as the French of

the Slavic world, possibly reflected here.

The

orchestra was then joined by the Polish violinist Anna Maria Staśkiewicz for

that glorious work, the Violin Concerto in A major, Op. 8 (1902).

The Allegro

moderato has a powerful thematic basis to which she brought intense

expressiveness. She had established an excellent musical rapport with Pletnev

and the RNO. The Romanza. Andante is an exquisite extended lyrical melody of love,

loss and nostalgia. She played the themes most affectingly and emotionally. The

Finale. Vivace assai is full of

virtuoso flourishes of a tremendously challenging type which she seemed to find

less than comfortable on occasion.

After the interval, two works, both symphonic poems, for which Karłowicz

is justifiably famous. Both are rather lugubrious stories, seeming favourites

with the Polish temperament. First, the Symphonic

poem Stanisław and Anna Oświecim, Op. 12. Considered his greatest symphonic

poem it involves a legendary incestuous love affair that flowered in the 17th

century (a brother and sister are ignorant of their close relation and discover

it after falling in love). The two protagonists were even believed by the

composer to have been buried in a chapel in Krosno. The tragic legend may well

have elements of truth but has been embellished. However the veracity of this

fraught story need not concern us. The RNO orchestra dealt well and skillfully

with the two themes - the Stanisław theme is marked in strength and energy and

the Anna theme far more lyrical. There is another melody the 'motif of tragic

fate' that appears on various occasions. There is an impressive funeral march

before the finale. The drama was certainly there and expressed by the orchestra

but perhaps not with the fullest emotional abandonment and commitment. The commentator Grzegorsz Michałski observes

in the programme notes that this composition is regarded as Karłowicz's finest

orchestral work placing the composer among the masters of 'the necromantic orchestra.' This is a Polish term quite new to me containing

all manner of connotations.

The second

symphonic poem, and the shortest, Symphonic

poem A Sorrowful Tale, Op. 13 (1908). The programme here is even more important

as it chronicles in music, according to Karłowicz:

'...

the mood and feelings of a man in whose head the thought of suicide is beginning to germinate....it leads to a

struggle beyween the will to life and the idée fixe of suicide. That struggle

is played out between the two contrasting themes. The latter wins: a shot rings

out....[played on a tam tam and not a pistol shot which Karłowicz

originally wanted] the man falls ever more

deeply into nothingness.'

The RNO under Pletnev responded far more intensely to this story than

the previous one. The adventurous instrumentation was dealt with in orchestral virtuosic

style. The writing is rather expressionist in mood and genre which Pletnev

seemed to understand instinctively.

So rather an educational concert for me, exploring the most significant

Polish instrumental and orchestral music between Chopin and Szymanowski. I felt

Karłowicz to be a major composer whose creative work was brutally interrupted

by Nature in an avalanche whilst pursuing his understandable passion (listening

to the aspirations within his compositions) of mountain climbing.

PADEREWSKI DAY

|

| From the film Moonlight Sonata starring Ignacy Jan Paderewski |

Sala Moniuszki

Teatru Wielkiego – Polish National Opera Symphonic Concert

DANG THAI SON piano

SINFONIA VARSOVIA

JACEK KASPSZYK conductor

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

I

must thank Artur Belecki, the writer of the notes for this concert, for reminding

me to turn back to the highly entertaining and humanly inspiring The Paderewski Memoirs (London 1939). The notes appear in the remarkably thorough

and well organized book of the festival, a model of its kind. Paderewski writes

in the early 1880s that as well as teaching at the Conservatory in Warsaw he

was fiendishly broadening his general education which he felt was inadequate (in

Mathematics, Literature, History) with four teachers a day!

A newspaper editor offered him the opportunity to write music criticism.

He wrote: 'But at that time I was not ready

for making criticism for the simple reason that I had no bitterness in myself.

I do not know if critics must have bitterness, but generally they have. I

must confess I always feel that.' (p.91)

A great pity we did not meet as I am rarely bitter but still fondly hope to

retain acute musical judgment! I am with the great English essayist William Hazlitt

(1778-1830) when he writes in the magnificent essay On Criticism in Table Talk:

Essays on Men and Manners (1822).

I would rather be a man of disinterested taste and

liberal feeling, to see and acknowledge truth and beauty wherever I found it,

than a man of greater and more original genius, to hate, envy, and deny all

excellence but my own [...] A genuine

criticism should, as I take it, reflect the colours, the light and shade, the

soul and body of a work.

Or, may I add,

a performance. So to my much maligned present occupation...

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941)

Piotr Betlej

Op 10 N 1 2016 © Galerie Roi Doré

Paderewski is such an underestimated composer of

affecting lyrical and poetic piano music which speaks directly to the heart and

sensibility rather than burdening the intellect with high seriousness. The music

of Paderewski wears its learning lightly with poetry, charm, elegance

and refinement of the highest order.

Dang

Thai Son has remained a popular artist in Poland for many years for excellent

Chopinesque reasons. This Vietnamese -

Canadian pianist was propelled to the forefront of the musical world in October

1980, when he was awarded the First Prize and Gold Medal at the Xth

International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw. It was also the first time

that a top international competition was won by an Asian pianist. But tonight he was playing significant compositions

by Paderewski.

He

opened his programme rather gently with a group of smaller pieces of which

Paderewski is a master. The Elegy in B

flat minor, Op. 4 (1880) was suffused in nostalgic reflection and repose. His

luminous refined tone was immediately obvious. Then the Polish Dances, Op. 5 No. 1 Cracovienne

in E major No. 2 Mazurka in E minor No.

3 Cracovienne in B flat major. I

found he understated these dances, the mazurka having an almost improvisatory

feel. The Krakowiaks I found rather

held back in their rhythmic 'snap' and verve.

This

was followed by a group from Miscellanea.

Série de morceaux pour piano op. 16 (1885–1896) No. 2 Melody in G flat major No. 1 Legend

in A flat major No. 4 Nocturne in B

flat major. The Mélodie is such a work of pure melodic charm and

grace, even sentimentality, to which Son brought a glowing cantabile and counterpoint.

The Legend in A flat major possesses

such an attractive, accessible theme and

musical narrative which appears to mirror Poland's fraught history. The

beautiful Nocturne in B flat major, quite

possibly my favourite piano work by Paderewski, was played with elegance,

grace, sensitivity, sensibility and charm. I was as ever enraptured. There is

great civilization and refinement behind Son's playing which would escape those

seeking for more robust executants.

Finally

in this group of small pieces, from the Humoresques

de Concert op. 14 (1886–1887) the delightful and famous Minuet in G major played with such childlike

innocence, expressive delicacy of tone, touch and superb articulation -

featherlight. Followed by the Cracovienne

fantastique in B major. This too was expressive within the carefully

contrived dynamic range and contained perfect rhythm. The allure and beguiling

nature of a world that existed before the Great War was manifest here.

After

the interval the Paderewski Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 17.

|

| Paderewski at 24 - a close likeness to his appearance during the writing of the concerto |

Paderewski was only 28 when he composed

this concerto and was scarcely known as a musical figure. He had made extensive

studies with Theodor Leschetizky and in 1888, the year of its composition, he

made his debut in Paris and Vienna. Paderewski wrote in his memoirs:

When

I finished [the] concerto, I was still lacking in experience. I had not even

heard it performed—it was something I was longing for. I wanted to have the

opinion then of a really great orchestral composer. I needed it. So without

further thought I took my score and went directly to Saint-Saëns. But I was

rather timid … I realised on second thoughts that it was, perhaps, presumption

on my part to go to him. Still I went to his house nevertheless. I was so

anxious for his opinion. He opened the door himself. ‘Oh, Paderewski, it’s you.

Come in,’ he said. ‘Come in. What do you want?’ I realised even before he spoke

that he was in a great hurry and irritable, probably writing something as usual

and not wanting to be interrupted. ‘What can I do for you? What do you want?’ I

hesitated what to answer. I knew he was annoyed. I had come at the wrong moment

… ‘I came to ask your opinion about my piano concerto,’ I said very timidly. ‘I

——.’ ‘My dear Paderewski,’ he cried, ‘I have not the time. I cannot talk to you

today. I cannot.’ He took a few steps impatiently about the room. ‘Well, you

are here so I suppose I must receive you. Let me hear your concerto. Will you

play it for me?’ He took the score and read it as I played. He listened very

attentively. At the Andante he stopped me, saying, ‘What a delightful Andante!

Will you kindly repeat that?’ I repeated it. I began to feel encouraged. He was

interested. Finally he said, ‘There is nothing to be changed. You may play it

whenever you like. It will please the people. It’s quite ready. You needn’t be

afraid of it, I assure you.’ So the interview turned out very happily after

all, and he sent me off with high hopes and renewed courage. At that moment in

my career, his assurance that the concerto was ready made me feel a certain

faith in my work that I might not have had then. (The Paderewski Memoirs London

1939 p. 149-50)

I

do not want to give a detailed review of this fine piano concerto and an

excellent performance (with a few very minor solecisms) save to say it is a

great pity that it has been so rarely performed. This is changing. The concerto

is such a lyrical and grand work full of piano pyrotechnics, noble harmonies,

dance energy and infectious charm.

I

felt Son played the Allegro with great authority and idiomatic

grasp as well as commitment. He was not assisted by the conductor Kaspszyk who

I felt allowed too inflated a dynamic to swamp the soloist. The Romanza:

Andante expressed the

ardent simplicity of the harmonies – one of my favourite piano concerto

movements from the second half of the nineteenth century. Son gave his phrasing intense musicality and sensitive phrasing and nuance. It reminds me of a

superb film score for say an intensely romantic French love affair

set in Provence directed by Francois Truffaut. In our imaginations we

could be bowling along a poplar-lined route secondaire past

hills of vineyards with Catherine Deneuve or Stephane Audran in the passenger

seat of a Chapron Citroen cabriolet.

Her hair is wonderfully awry in the wind as we head through rolling sunlit

pastures towards une belle gentilhommiere and nights

of sophisticated sensual bliss, days of cultivated tastes, food and wine.

Ah…what we have lost of true civilization and culture in 2018…Paderewski

had it all.

Orchestrally

the Allegro molto vivace did not quite possess the dance

rhythms with sufficient energy and driving tempo to inspire this excellent

pianist to the heights he would naturally aspire to playing patriotic Polish

music.

A

perfectly lovely evening for a critic who is not the slightest bitter or ashamed

at confessing a love for this charming seductive and undemanding music.

Polish National Opera Symphonic concert

VADYM KHOLODENKO piano

LUDMIL ANGELOV piano

SINFONIA VARSOVIA

JACEK KASPSZYK conductor

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

|

| Silver Coffin Tomb of St. Stanisław, Wawel Cathedral, Kraków |

The

first piece in this interesting concert was a rather rare orchestral work by

Liszt which I had never heard before. The Orchestral

interlude ‘Salve Polonia’ from the Oratorio Saint Stanislaus (1884). In

1843 Liszt arrived in Kraków to give concerts and visit the city. At the

cathedral on the Wawel hill he learned of the martyrdom of St. Stanisłaus which

moved him to write an oratorio. Although incomplete, significant passages survive

including this one. The instrumentation is outstanding in the development of

two of the themes 'Boże, coś Polskę'

(God Thou who Poland) and the anthem 'Jeszcze

Polska nie zginęła' (Poland Is Not Yet Lost). Such festive and patriotic

music in response to the 'Polish Question' (the brutal partitions) which

preoccupied so many artists in Europe of the time.

|

| Vadym Kholodenko |

Then

Vadym Kholodenko came forward to play the Alexander Scriabin Piano Concerto in F sharp minor, Op. 20

(1897). The lyrical melodies and harmonic progressions throughout his only

piano concerto and first published orchestral piece owe a great debt to

Chopin. In the opening Allegro Kohlodenko with a luminous tone and cut velvet touch affectingly brought

out the long lyrical opening legato melody. Harmonious and flowing like a river

yet rhapsodic and impassioned. The Andante

opens with a type of Russian folk tune

on the piano with elegant and refined orchestration. The piano offers a type of

obbligato accompaniment to the variations that follow. Kholodenko gave this

movement a seductive mood of improvisation, at one moment energetic then meditative and reflective.

One could not help but notice the beautiful balletic movement of Kholodenko's fingers on

the keyboard. The Allegro moderato begins

with a type of polonaise and secondary lyrical theme evolving to the final

chords which take us back to the opening of the work, the circle complete. I

thought this a ravishing piece of music and only wished the orchestra under

Jacek Kaspczyk had been rather quieter, the better to hear the detail in Kholodenko's

profound understanding of Scriabin. I gasped when he embarked on Vers la Flamme as an encore - the most

unsettling, luminous and yet transcendent account of it by any living pianist.

|

| Rare picture of the young Moritz Moszkowski (1854-1925) |

After

the interval a recently discovered piano concerto by Moritz Moszkowski

[1854–1925], the Piano Concerto in B minor, Op. 3 (1874). He composed many polonaises, mazurkas and a challenging and fine Piano Concerto in E major. This

youthful work in B minor remained in limbo until Bojan Assenov, a pianist and

composer from Berlin, wrote a dissertation on Moritz Moszkowski which included

a catalogue of his works (2009). He found the concerto in the Bibliothèque

nationale de France. Through the dissertation, the existence of this work was

then discovered by the prize-winning Bulgarian pianist Ludmil Angelov.

Moszkowski

played it for Liszt who was impressed. Moszkowski wrote: ‘He even arranged a small private concert for Madame [Baroness Olga]

von Meyendorff in which I played it with him on two pianos.’ He finally

dedicated the work to Liszt. The performance record is blank until 9 January

2014 when Angelov performed it once again. The concerto remained unpublished. ‘I did not find at that time, of course, a

publisher for such an extensive work’, Moszkowski wrote in his diary. ‘When I was later no longer desperate for a

publisher I did not like the piece any more. I worked it all over, sold it, but

paid back the fee at the last moment and kept my concerto because it displeased

me again.’ And further in a humorous vein, Moszkowski also wrote: ‘I should be happy to send you my piano

concerto but for two reasons: first, it is worthless; second, it is most

convenient (the score being four hundred pages long) for making my piano stool

higher when I am engaged in studying better works.’

|

| Ludmil Angelov |

The

concerto is far beyond what one might be tempted to term 'a student work'. The Allegro is good humoured and Angelov communicated

this feeling admirably. I felt the opening had an Arabic or oriental quality to

the theme and orchestration. The three lyrical themes of the Adagio revealed Angelov to have a fine cantabile tone and most eloquent phrasing. In the Scherzo. Molto vivace he brought much verve and vivacity although it seemed slightly trivial to me. More exuberant themes pepper the final overly-long

(a concerto in itself?) Allegro sostenuto

– Allegro con spirito with a remarkably extended, and to my knowledge

unique, break for the piano before returning with the first of two virtuosic

cadenzas.

As he left the stage, the pianist Angelov appeared rather worn by his

sterling yet absolutely convincing efforts with this formidable 'new' work. His

encore was an affecting and sensitive performance of the Chopin Nocturne No. 20 in C-sharp minor, Op. posth., Lento con gran espressione. I would certainly like to hear

more Chopin from this pianist...

|

| Ludmil Angelov with Sinfonia Varsovia conducted by Jacek Kapszyk |

24.08 FRIDAY 8.00 p.m.

Witold Lutosławski Concert Studio of Polish Radio

HALKA Stanisław Moniuszko [1819–1872] (Italian version)

Opera in concert version

TINA GORINA soprano (Halka)

MONIKA LEDZION-PORCZYŃSKA soprano (Sofia)

MATHEUS POMPEU tenor (Jontek)

ROBERT GIERLACH baritone (Janusz Gianni)

RAFAŁ SIWEK bass (Stolnik Alberto)

KAROL KOZŁOWSKI tenor (Wieśniak Contadino)

Chorus Soloists: KRZYSZTOF SZYFMAN bass (Dziemba Gemba) MATEUSZ STACHURA baritone (Dudarz Zampognaro, Goście Contadini) PAWEŁ CICHOŃSKI tenor (Goście Contadini)

PODLASIE OPERA AND PHILHARMONIC CHOIR, VIOLETTA BIELECKA choir director

EUROPA GALANTE

FABIO BIONDI conductor

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

In many ways it is a great shame I have experienced the opera HALKA only in the concert version however distinguished the orchestra and soloists. The Warsaw première of the opera Halka by Stanisław Moniuszko on 1 January 1858 with a intensely poetic and pantheistic libretto by Włodzimierz Wolski was a fulchrum in the history of Polish music. The original libretto was also translated into Italian but never performed in that language. It was the first Polish national opera.

From the moment of its Warsaw première in 1858, general interest in Moniuszko’s opera continued to grow. In June 1860 Warsaw daily press informed readers: 'A request for the score of Halka has been received from Prague'. Moniuszko visited Paris twice, the opera capital of Europe. Promotion of his work in the French capital proved fruitless. Some associate the composition of the opera and the lot of heroic yet betrayed peasant class (Halka) and a mendacious class of nobility (Janusz) with the turbulent peasant revolt events of the Kraków Uprising of February 1846. It has been performed well over a thousand times in Warsaw.

As a foreigner I am ill equipped to comment authoritatively on the profound impact of this first great national opera musically and socially on the psyche of contemporary Poles. Suffice to say that the patriotic music is dramatic, engaging and satisfying on various levels with a number of beautiful arias. I loved Halka's aria 'Gdyby rannym słonkiem' and Jontek's aria 'Szumią

jodły na gór szczycie' The first performance of the two-act version was in a concert performance in Vilnius on 1 January 1848. This four-act version was first performed in Warsaw on 1 January 1858.

The story is rather melodramatic with a universal social message. I have read a rather whimsical libretto in English rhyming couplets e.g.

Janusz (Johnny): Just as I have long been dreading

She shows up before the wedding

Stolnik: Lowly peasants gone astray

I simply don't know what to say

This was the first performance in Italian. In this original Italian version, HALKA should endear itself to Italian audiences who are so fond of such passionate tragic stories of unrequited love. Plans have been discussed for a contemporary performance in Italian in Italy.

In this concert performance I did miss the costumes and the spectacular Polish folk dancing that lies at the heart of any properly staged version, especially the grand Mazur whose theme is justifiably famous throughout the world. Many of the voices (particularly male) were excellent in the roles. Europa Galante under Fabio Biondi on period instruments rather brilliantly produced a lower level instrumental dynamic which revealed more details of the voices and diction than a louder modern orchestra permits. Certainly any future staged production outside Poland should go a long way to establishing respect for Polish nineteenth century opera abroad.

The story is rather melodramatic with a universal social message. I have read a rather whimsical libretto in English rhyming couplets e.g.

Janusz (Johnny): Just as I have long been dreading

She shows up before the wedding

Stolnik: Lowly peasants gone astray

I simply don't know what to say

This was the first performance in Italian. In this original Italian version, HALKA should endear itself to Italian audiences who are so fond of such passionate tragic stories of unrequited love. Plans have been discussed for a contemporary performance in Italian in Italy.

In this concert performance I did miss the costumes and the spectacular Polish folk dancing that lies at the heart of any properly staged version, especially the grand Mazur whose theme is justifiably famous throughout the world. Many of the voices (particularly male) were excellent in the roles. Europa Galante under Fabio Biondi on period instruments rather brilliantly produced a lower level instrumental dynamic which revealed more details of the voices and diction than a louder modern orchestra permits. Certainly any future staged production outside Poland should go a long way to establishing respect for Polish nineteenth century opera abroad.

A pandemonium of cheering, shouting and stamping of feet greeted the conclusion of the opera.

|

| Europa Galante under Fabio Biondi and the Podlasie Opera and Philharmonic Choir |

|

Monika Ledzion-Porczyńska - Zofia (Sofia), Robert Gierlach- Janusz (Gianni)

|

|

Tina Gorina - Halka, Matheus Pompeu - Jontek

|

|

Rafał Siwek - Stolnik (Alberto)

|

|

| Fabio Biondi (conductor) Tina Gorina - Halka, and Matheus Pompeu - Jontek |

|

| Matheus Pompeu - Jontek |

|

| The Podlasie Opera and Philharmonic Choir |

|

| Robert Gierlach- Janusz (Gianni) |

23.08 THURSDAY 8.00 p.m. Moniuszko

Auditorium at the Teatr Wielki – Polish National Opera Symphonic concert

LEIF OVE ANDSNES piano

BERGEN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

EDWARD GARDNER conductor

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

This quite remarkable concert

gave the fortunate audience the opportunity to hear a neglected piano concerto

by Benjamin Britten, played by one of the greatest pianists of our time. More

of that later, as the evening opened with the Paderewski Overture in E flat major for orchestra (1884). The young composer

(24) was deeply involved in orchestral writing during his studies in Berlin

when he wrote this delightful overture. Certainly immersed in rather Classical

material one anticipates an opera which was clearly his intention.

|

| Portrait of the young Benjamin Britten |

Then to the rarely performed Benjamin Britten [1913–1976] Piano Concerto, Op. 13 (1938). One must consider two aspects in its gestation and composition. First the age of the twenty-five year old, who like all young men of ambition, was intent on building a career as a pianist and composer. Always suffering from stage fright, he feared appearing as the soloist when the work was premiered at a Prom concert in the summer of 1938 under the baton of Sir Henry Wood. Following the rehearsal he wrote to his publisher:

The piano part wasn’t as impossible to play

as I feared, & with a little practice this week ought to be O.K. It

certainly sounds 'popular' enough & people seem to like it all right.

|

| The young Benjamin Britten at the piano |

The audience were positive as were the reviews, although the first two movements considered stronger than the two following. ‘If music be indeed the food of love, I think you stand a very good chance’, commented Lennox Berkeley to whom he dedicated the work. The orchestral writing was extraordinarily brilliant. From the musical point of view Britten wrote in the program note:

'...was conceived with the idea of exploiting various important

characteristics of the pianoforte, such as its enormous compass, its percussive

quality, and its suitability for figuration, so that it is not by any means a

symphony with pianoforte, but rather a bravura concerto with orchestral

accompaniment.'

This often martellato work is clearly influenced by Prokofiev, Shostakovich

and possibly French composers such as Ravel.

Allied to these musical and

career considerations was the bleak historical moment in which the concerto was

written. This was on the eve of war with Germany that had begun to fold its dark

eagle wings over Britain and the rest of Europe. Preparations for aerial

bombardment in particular dotted the country with barrage balloons, trenches dug in city parks and masks against poison

gas handed out. Britten's diaries reveal personal fury that his own work, the

great musical culture of Europe and the pleasures of a civilized life were about

to be crushed in the mud. Those who had experienced the horrors of the Great War

(unlike Britten) understandably feared another or as The Week termed the policy of appeasement and the Munich

Agreement, had 'turned all four cheeks to Hitler'.

|

| Leif Ove Andsnes |

The exuberance, tension and

agitation of the Toccata. Allegro molto e

con brio that opens the concerto expresses a certain ambiguity of mood. Leif

Ove Andsnes brought enormous power, authority and irresistible forward drive to

this fantastically unsettling movement. Some commentators indicate that the

poignant Waltz. Allegretto, which has such an ominous,

sometimes brash, almost sinister air, may have been deeply influenced by the

ambiguous response to the Anschluss by

the Viennese. Andsnes expressed with

great insight the irony and shadows within this movement. The third

movement Impromptu. Andante

lento with which in 1945 Britten

replaced the original recitative and aria, is a powerful passacaglia

which the charismatic conductor

Edward Gardner of the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra came together with Andsnes to perturbing and disconcerting

effect. It was brought off magnificently.

|

| Leif Ove Andsnes |

The final movement March. Allegro moderato sempre a la marcia has

elements of the almost hysterical party, even 'cabaret' atmosphere of exuberant,

reckless carelessness, even humour which greeted the looming Moloch crouched across

the Channel. After this great performance a line from Thomas Mann toward the

epilogue of his Doctor Faustus came to

my mind 'Never had I felt more strongly

the advantage that music, which says nothing and everything, has over the

unequivocal word;'

|

| Leif Ove Andsnes and Edward Gardner |

After the interval the Symphony No. 2 in D major Op. 43 (1901-2) by Jean Sibelius [1865–1957]. The composer said of it: 'My second symphony is a confession of the soul.' There is some controversy over whether this is a nationalist work as at the time of composition Finnish language and culture were proscribed by the Russians. Sir Colin Davis quoted the English poet William Wordsworth for one of his recordings of the symphony with the London Symphony Orchestra:

Grand in itself alone,

but in that breach

Through which the homeless voice of waters rose

That dark deep thoroughfare, had Nature lodged

The Soul, the Imagination of the whole.

Through which the homeless voice of waters rose

That dark deep thoroughfare, had Nature lodged

The Soul, the Imagination of the whole.

Like so many great composers,

Sibelius was inspired by Italy which became his second beloved country and

where he began this symphony in Rapallo, perched on its rock. In his

imagination he had played with Dante's Divine

Comedy and the 'Stone Guest' from Don

Giovanni. Sibelius and Mahler met in Helsinki in 1907. Sibelius later

recalled:

When our conversation touched on the essence

of symphony, I said that I admired its severity and style and the profound

logic that created an inner connection between all the motives. This was the

experience I had come to in composing. Mahler’s opinion was just the reverse.

“Nein, die Symphonie müss sein wie die Welt. Sie müss alles umfassen.” (No, the

symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.)

|

Symposium

(1894) Akseli Gallen-Kallela

Lt to Rt .Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Oskar Merikanto, Robert Kajanus

and Jean Sibelius.

|

Edward Gardner (immensely communicative, intensely physically active and charismatic) with the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra brought magnificent ensemble to this profound, demanding and unconventional work. Sibelius certainly had grandiose ideas concerning its form: 'It is as if the Almighty had thrown down the pieces of a mosaic for heaven’s floor and asked me to put them together.' The first movement Allegretto opens in 'heavenly pieces' with many tempo indications that only cohere after some time. The second movement Allegretto. Tempo andante ma rubato unusually opens with a timpani roll. Slowly the volume, tempo and pitch rise to a fortissimo in the brass (powerful and strident in this orchestra) followed by a sudden and dramatic contrast of a tender theme on the violin played pianissimo.

The third movement 'Vivacissimo' is a precipitate scherzo

with a short an eloquent and moving trio section with oboe inspired by the suicide of

Sibelius's sister-in-law. Without pause the themes in the Finale. Allegro moderato build in monumental

and rhapsodic stature and intensity, as majestic as forbidding granite crags. The

great Finnish conductor of Sibelius Robert Kajanus wrote of this movement that

it '...develops towards a triumphant

conclusion intended to rouse in the listener a picture of lighter and confident

prospects for the future.'

|

| Edward Gardner |

I found the emotional tension and sheer volume of opulent sound that Edward Gardner constructed with the Bergen Philharmonic transcendentally overwhelming. A musical experience of the first water.

|

| Edward Gardner with the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra |

Ballroom at the Teatr Wielki – Polish National

Opera Chamber concert

ANDRZEJ BAUER cello

TOBIAS KOCH piano

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

|

| Auguste Franchomme (1808-1884) |

One of the most attractive aspects of this festival are the concerts devoted to musician friends and acquaintances of Fryderyk Chopin whose former fame and lustre has faded somewhat as time passes. This concert was devoted to the French composer and cellist Auguste Franchomme (1808-1884) whom Chopin met and befriended in Paris in the early 1830s. He dedicated a number of works to the cellist, including the great cello sonata and at times performed with him. Franchomme was also a close friend of Felix Mendelssohn. He was an illustrious figure in the musical life of Paris and pioneered revolutionary bowing techniques for his instrument and precision techniques in left-hand playing.

Koch and Bauer opened their

concert with Franchomme's Fantasy for

cello and piano on a theme from Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, Op. 40. I

found this an absolutely delightful and diverting confection, the tonal and textural

balance established between the historic Erard

period piano and cello only added to the pleasure. Rather heartfelt and

sensitive at times. Apart from sections of the Overture, we heard Sarastro's aria O Isis und Orsiris the work concluding amusingly with Papageno's Hm,

Hm, Hm.

This was followed by two Franchomme

Caprices, Op. 7 No. 9 in B minor and No.

12 in C major. Bauer gave impressively virtuoso accounts of these striking

works, the B minor putting me in mind of J.S.Bach and the C major rather light

and pleasant.

Koch then joined him to perform the Beethoven/ Franchomme Sonata in A minor Op. 23, originally for

piano and violin. The Presto I found

interesting but lacking in excitement considering the tempo indication, the Andante

scherzoso, più Allegretto rather witty with its jolly thematic motif. They

co-operated well in this movement and maintained and enviable balance. The Allegro

molto was satisfyingly passionate, dramatic and energetic with cello rather

than violin.

After the interval an arrangement

by an Irish pianist and composer I was not familiar with, George Alexander

Osborne [1806–1893]. he was from the same circle of musicians. An interesting

study could be made of the surprising number of Irish classical musicians and

composers working on the continent during

the 19th century. He and Franchomme co-operated on a Duo Concertant on a theme from Donizetti’s opera Anna Bolena. I

found the work charming and innocuous, something one might have listened to at

Bath Spa in the Assembly Rooms or whilst taking tea and 'staring and despising'

at the visiting company from London taking the waters.

Then to a level of rather significant

musical seriousness and virtuosity on the art of Bauer with Franchomme and his Etudes Op. 35 - No. 5 in C minor, No. 7

in A minor and No. 12 in G-sharp minor. The A - minor I found particularly

virtuosic and formidable with its detaché

execution. The G-sharp minor had a darkly ominous mood with a remarkable legato

melody line maintained for two voices. Bauer brought a gloriously rich mahogany

tone to the Etude in C -sharp minor

Op. 25 No.7.

In the final work of this

concert I had been much anticipating hearing the fruits of the co-operation between Chopin

and Franchomme in the Grand Duo Concertant

in E major on themes from Meyerbeer’s opera Robert le diable, DbOp. 16A,

Op. 23 (1832–1833). As soon as the work began I became immediately aware of the

gulf that separates true melodic genius in composition from great talent. I found the tempo they adopted a

trifle slow yet the execution on other levels fine indeed with again that superb

unctuous tone from the Bauer cello. The piano accompaniment by Koch to this lyricism,

although notable and impressive, could have had more Chopinesque finesse. In a

way I felt the interpretative approach to this work could overall have had more drive

and energy. Personal taste once again on the horizon?

As encores an emotionally moving

account of the Paderewski Nocturne arranged

for cello - absolutely beautiful on this instrument. Then a profoundly

nostalgic and deeply touching rendition of the Largo from the Chopin Cello

Sonata Op.65. The luscious, opulent tone Bauer produces from his cello seduced

me once again...

22.08 WEDNESDAY 8.00 p.m.

Stage of the Teatr Wielki – Polish National Opera

Symphonic concert

JAN LISIECKI piano

ORPHEUS CHAMBER ORCHESTRA [This orchestra perform without a conductor]

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

[Photographs by W. Grzędziński/NIFC]

This

remarkable orchestra opened the concert with a difficult work by the Polish composer Henryk

Mikołaj Górecki [1933–2010] Trzy utwory w

dawnym stylu na orkiestrę smyczkową (1963) Three Pieces in Old Style for

string orchestra Utwór Piece I Utwór Piece II Utwór Piece III. My mind however

is completely clouded by the grim associations that his characteristic instrumental

voice creates in my soul by his well-known Third Symphony The Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. This was used in a BBC/TVP/CBCX/ZDF Co-production released in 2005 entitled

Holocaust - A Music Memorial Film from

Auschwitz which marked the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the camp.

There were several orchestras and bands in the camp and music was a part of daily life. Primo Levi wrote that classical music in Auschwitz was 'the perceptible expression of the camp's madness.' I closed my ears, perhaps unfairly. Far more than any of the other pieces used in the film, his powerful voice is forever engraved with horrifying associations on my human heart.

There were several orchestras and bands in the camp and music was a part of daily life. Primo Levi wrote that classical music in Auschwitz was 'the perceptible expression of the camp's madness.' I closed my ears, perhaps unfairly. Far more than any of the other pieces used in the film, his powerful voice is forever engraved with horrifying associations on my human heart.

|

| The young Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) |

For me a glorious change of mood from this sombre beginning. The orchestra was joined by Jan Lisiecki for Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto in G minor, Op. 25. Of Mendelssohn as a pianist Clara Schumann once wrote to Robert 'For a few minutes I really could not restrain my tears. When all is said and done, he remains for me the dearest pianist of all.' It is all to easy to forget that Mendelssohn was celebrated as a pianist as well as composer - something we have not forgotten concerning Chopin and Liszt. Mendelssohn was only 22 (much the same age as Lisiecki) when he completed this concerto in 1830-1 and undoubtedly full of boundless creative and youthful energy. Alfred Einstein wrote so appropriately of his music: 'He had no inner forces to curb, for real conflict was lacking in his life as in his art.....But his instrumental and vocal works are alike masterpieces of refinement, clarity and control.'

|

| Jan Lisiecki |

Matters begin rather precipitately with a dramatic gesture in this concerto. There is no long orchestral tutti introduction as in a Classical concerto before the piano enters - the entry is combined. For this reason I felt it could have had more explosive 'fire' at the beginning. Lisiecki took the Molto allegro con fuoco at such an exciting cracking tempo with quite brilliant articulation and forward drive it precluded any injection of great expressive charm which the movement needs if it is to escape the charge of superficial facility and lightness. 'He [Mendelssohn] played the piano as a lark soars...' wrote Ferdinand Hiller. If one watches birds they dip and glide in the currents of air in artistic arabesques. On the other hand the Andante was most affecting in its expressiveness with a truly glorious tone. A true 'Song Without Words'. I could not help but reflect on the emotional maturity this pianist has gained since I last heard him some time ago now. Without a break the Presto – Molto allegro vivace. Lisiecki launched into the diverting 'tune' of this movement with boundless youthful energy that carried all my reservations before it. Also he was playing splendidly without a conductor to assist him through difficult orchestral and solo synchronizations.

How the Victorians with their light

social pretensions loved Mendelssohn for this very lack of anguished Teutonic philosophical reflection on the state of

one's soul. '...a thing rapidly thrown

off...' as the composer described it. This is not to say trivial...

|

| Jan Lisiecki and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra |

After the interval the Mendelssohn Piano Concerto in D minor Op. 40 (1837). I am privileged to allow Schumann to speak for me. 'It is as though a tree had been shaken, and the ripe, sweet fruit had promptly fallen.' The Second Concerto resembles the first in structure and texture but I felt Lisiecki was far more accomplished expressively in this work. The Allegro appassionato had far more 'air' to the phrasing and we were given time to follow the charming modulations and relatively undemanding keyboard writing. Again I thought of the heartfelt and affecting cantilena in the Adagio: Molto sostenuto replete with moving introspective expressiveness and beautiful tone colour. Perhaps the composition reflected both the tragedy of Mendessohn's father's death and his joyful honeymoon that followed so soon after. Then to the Finale. Presto scherzando. This movement is so happiness inducing I have nothing but praise for this young man in raising my spirits with his airy, light articulation and dotted rhythmic momentum.

Finally

the beloved Mendelssohn Symphony in A

major (‘Italian’), Op. 90 (1833).

Conceived on a journey to Italy in 1830 (at the passionately impressionable age

of 21), the work effortlessly evokes the Italian campagna. He

was guided on his Grand Tour and

enthused for it by the Italienische Reise (Italian Journey) of Goethe. He painted watercolours of the

landscape and wrote of the 'exhilarating impression made on me by the first

sight of the plains of Italy.' The intense Mediterranean light seduced him.

I have nothing but the highest praise for the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra in their

account of this work. It was formed in 1972 'to combine the intimacy and warmth

of a chamber ensemble with the richness of an orchestra.' The lightness and

transparency of the remarkable strings have the texture of the finest Venetian

lace from the lagoon island of Burano.

|

| The Amalfi Coast by Felix Mendelssohn |

|

| Lake Como by Felix Mendelssohn |

|

| Florence - The Duomo by Felix Mendelssohn |