77th Duszniki Zdrój International Piano Festival, 5-13 August 2022, Poland

77th Duszniki International Piano Festival

5-13.08.2022

30TH ART DIRECTOR’S FESTIVAL – PIOTR PALECZNY

Honorary Patronage of the President of the Republic of Poland, Andrzej Duda

Calendar of Festival Events

Link to detailed recital programmes, biographies of artists and Artistic Director's introduction

https://app.box.com/s/g9bqmwkuw059ny77es3pictf733fad7s

| 5.08.2022 Friday | 8 pm | Bruce LIU Inaugural concert |

| 6.08.2022 Saturday | 4 pm | Jonathan FOURNEL 1st Prize at the Queen Elizabeth Competition – Brussels 2021 |

| | 8 pm | Bomsori KIM – violin Rafał BLECHACZ – piano |

7.08.2022 Sunday | 4 pm | Juan PEREZ FLORISTAN 1st Prize at the Arthur Rubinstein Competition – Tel Aviv 2021 |

| | 8 pm | Lucas & Arthur JUSSEN Piano Duo |

| 8.08.2022 Monday | 4 pm | Dmytro CHONI 1st Prize – Santander 2018 Laureate – Leeds 2021 3rd Prize at the Van CLIBURN Competition 2022 |

| | 8 pm | DANG Thai Son |

| 9.08.2022 Tuesday | 4 pm | Chloe Jiyeong MUN 1st Prize – Takamatsu 2014 1st Prize – Genewa 2014 1st Prize – Busoni 2015 |

| | 6:30 pm | Charity concert of the participants of the 21st Master Course |

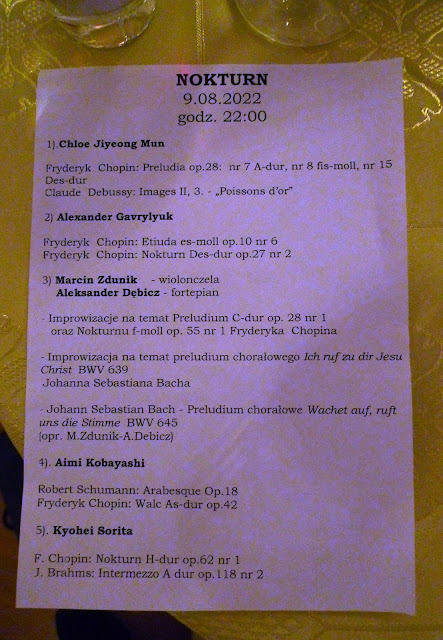

| | 9 pm | NOKTURN – host of the evening: Marcin MAJCHROWSKI |

| 10.08.2022 Wednesday | 4 pm | Aimi KOBAYASHI |

| | 8 pm | Alexander GAVRYLYUK |

| 11.08.2022 Thursday | 4 pm | Kyohei SORITA |

| | 8 pm | Marcin ZDUNIK – cello Aleksander DĘBICZ – piano |

| 12.08.2022 Friday | 4 pm | Alim BEISEMBAEV 1st Prize – Leeds 2021 |

| | 8 pm | Vadym KHOLODENKO |

| 13.08.2022 Saturday | 4 pm | Yunchan LIM 1st Prize at the Van CLIBURN Competition 2022 |

| | 8 pm | Jan LISIECKI Final concert |

Weekend concerts at the FRYDERYK Hotel

6.08. – Saturday

11 pm – Marcin Wieczorek

12 am – Krzysztof Wierciński

7.08. – Sunday

11 pm – Aleksandra Dąbek

12 am – Józef Domżał

13.08. – Saturday

11 pm – Julia Łozowska

12 am – Filip Michalak

21st National Piano Master Course in Duszniki-Zdrój (Master Class)

August 6-9, 2022, from 9.30-13.30 Alexander GAVRYLYUK

10-13 August 2022 from 9.30-13.30 prof. Vanessa LATARCHE

Participation of Russian artists

Due to the dramatic development of the war – the brutal and bloody aggression of Russia against the independent nation of Ukraine, due to the violation of all provisions of international law – unfortunately, it has become impossible for us to maintain the performances by Eva Gevorgyan (8 August), Philipp Lynov (9 August) and a master class by Professor Natalia Trull (6-9 August), scheduled as part of the 77th International Chopin Festival in Duszniki-Zdrój.

We would like to stress that we sincerely hope that peace will be restored in the near future!

|

| The opening flower-laying ceremony of the Festival at the Chopin Memorial Duszniki Zdroj |

|

| Prof. Piotr Paleczny at the symbolic opening of the Prof. Piotr Paleczny Avenue in the Spa Park at Duszniki Zdroj on 9 August 2022 |

|

| The Dworek during the Nokturn with Prof. Piotr Paleczny, the Artistic Director of the Duszniki Festival, seated on the right. The presenter of the evening, Marcin Majchrowski, is standing on the far left The Theme of this Nokturn was Chopin and the Romantic Myth |

|

| The Nokturn Programme |

TUESDAY, 9 AUGUST 2022

CHOPIN MANOR 4.00 PM

Piano recital

CHLOE JIYEONG MUN

Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

Scenes from Childhood (Kinderszenen), Op. 15 (1838)

|

The Three Children of Henry, 1st Marquess of Exeter (1754-1804), by Sir Thomas Lawrence, P.R.A. (1769-1830)

Of Foreign Lands and Peoples

Mun has a beautiful rounded and refined tone and touch at the instrument. Great simplicity here

A Curious Story

The internal polyphony was finely clarified by the moderate tempo

Blind Man's Bluff

Uplifting feeling of childhood humorous games in this performance

Pleading Child

This sounded quite authentically like 'pleading' - astonishing emotional access

Happy Enough

An Important Event

I felt rather dynamically over-inflated as it is an event seen through the eyes of a child

Dreaming

Poetic interpretation that took us into a world of intense sentiments, clouds of unreality. Glorious sound quality and touch

At the Fireside

A cosy chat and stories told

Knight of the Hobbyhorse

An attractive horse-riding rhythm but somewhat overdone as it is a wooden horse that moves only back and forth

Almost Too Serious

Communicated a true feeling of ambiguity here

Frightening

Childish ideas are immature and lead to whimsical fears

Child Falling Asleep

Rather an uncanny feeling of disembodiment as a child falls asleep, wakes suddenly and falls asleep again

The Poet Speaks

Presented a deeply poetic, lyrical piece

This remarkable,esoteric film made of Alfred Cortot advising on this work at a masterclass is well worth a few minutes of your time

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rNUNNNNj_Qw

Fryderyk Chopin (1810‒1849)

Fantasy in F minor, Op. 49 (1841)

Mun showed a perceptive grasp of the structure of this work. The introduction was calm and reflective followed by a triumphal account overall with much żal, anger and resentment.The chorale section was considered and deeply affecting making the re-emergence of emotional tumult all the more powerful with even more żal than on the first occasion, more urgency and building to the climacteric. She introduced an heroic tone and emotional intensity as the work progressed. The conclusion came as the expression of exhaustion of passionate emotions and a sense of resigned despair. A remarkable and formidable performance of this masterpiece.

INTERMISSION

Fryderyk Chopin (1810‒1849)

Nocturne in C sharp minor, Op. 27 No. 1 (1835)

Presented as a sensitive narrative of love

Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

Davidsbundlertänze, Op. 6 (1837)

She created a beautiful opening for this challenging work, the remarkable masterpiece Davidsbündlertänze (Dances of the League of David), Op. 6 (1837). This is a set of 18 pieces and one of the great works of Western Romantic piano literature. The Davidsbündler (League of David) was a music society founded by Schumann in his literary musings. The League itself was inspired by real or imagined literary societies such as those created by E.T.A Hoffmann. The major theme was based on a mazurka by Clara Wieck and was inspired by his love of her and hope for their union ('many wedding thoughts') which permeates all the works of this period. Her presence is rather subliminal throughout the whole cycle.

Literature and music had a symbiotic relationship for Schumann and was a source of the unique qualities of his genius. He was famous at this time as a perceptive music critic, even over knowledge of him as a composer. He considered music criticism, extra-musical criticism, to be an art form in itself. In this work it is clear he was gaining in musical self-confidence as a composer with his increasing attraction to the public. The masks of Carnaval are stripped away and the poet's face here revealed.

The pieces are not really dances but musical 'dialogues' concerning contemporary music that take place between Florestan (rasch-quick or hasty) and Eusebius (innig-intimate). Schumann created these characters to represent the active and passive aspects of his personality. The enigmatic description of No.9 reads 'Here Florestan stopped, and his lips trembled sorrowfully.' I cannot analyse here each of the eighteen movements of the work, although I would dearly love to do this. Save to say, Mun gave an energetic, electrical performance of Florestan, together with the other side of the human coin, the tender, 'feminine' cantabile that depicted the gentle lyricism of Eusibius. She captured much of the poetic, mercurial, impetuous, whimsical and lyrical aspects of Schumann's nature whilst preserving the unity of this cycle that allows us to experience ‘music as landscape’ (Charles Rosen).

LebhaftInnig

Mit Humor

Ungeduldig

Einfach

Sehr rasch

Nicht schnell

Frisch

Lebhaft

Balladenmäßig – sehr rasch

Einfach

Mit Humor

Wild und lustig

Zart und singend

Frisch

Mit gutem Humor

Wie aus der Ferne

Nicht schnell

Her encore:

1. A profoundly moving piano arrangement of Orfeo ed Euridice, Act II: Dance of the Blessed Spirits by Giovanni Sgambati. As fine as Egon Petri ....

This was an exceptional recital by a sensitive and gifted artist - one of the high points surely of the Duszniki Festival this year

MONDAY, 8 AUGUST CHOPIN MANOR 8.00 PM

Piano recital

DANG THAI SON

Jan Sebastian Bach (168–1750) / Samuel Feinberg (1890–1962)

Largo in A minor from the Organ Sonata in C major, BWV 529 (1730)

The eminent English musicologist Peter Williams discusses the "ingenious" structure of the movement which he describes as "bright, extrovert, tuneful, restless, intricate". There is "inventive" semiquaver passagework. A pleasant beginning but an unusual one because of its polyphonic complexity.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

|

| Mozart's Vienna 1785 |

Published by Artaria in 1784, interestingly in 2014, Hungarian librarian Balázs Mikusi discovered four pages of Mozart's original score (autograph) of the sonata in Budapest's National Széchényi Library. Until then, only the last page of the autograph had been known to have survived.

Piano sonata in A major, K.331 (1781–1784)

Andante grazioso - Tema con variazione

Menuetto – Trio

Alla Turca. Allegretto

I found his presentation of this sonata stylistically pure and completely charming, elegant, refined and graceful with just the right degree of tasteful affectation. Fine judicious use of the pedal and semi-detaché articulation. The choice of tempo for the Alla Turca seemed beautifully balanced with uplifting energy and life, sparkling and a quite delightful slightly detached left hand articulation.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Piano Sonata in E major, Op. 109 (1820)

Vivace ma non troppo, sempre legato – Adagio espressivo

Prestissimo

Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung. Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo

This sonata was composed in 1820 when Beethoven was completely deaf and suffering ill-health. However, it is an especially lyrical work. Clearly a fine performance, stylistically pure, the work is a profound personal statement by Beethoven which gives an impression of internal life.

The reflective parts of the Adagio espressivo are of the deepest philosophical introspection which I felt he succeeded in penetrating from the outset an a most soulful and expressive manner. Here was a song full of nostalgic yearning for lost affections. The staccato sections provided a marvellous contrast of sound texture and mood. The sonata breaks nearly all the rules of traditional sonata form.

The Prestissimo emerged as an immaculate yet irresistible force of glowing tone and sparkling articulation. We were presented with the expression of divine nostalgic laments, regrets in life, the meditative preoccupations and loss of love leading to an ultimate resignation under the stronger force of destiny. His staccato articulation throughout was very fine with much colour and nuance relieving the granite.

Beethoven for me sometimes requires the communication of a feeling of the struggle of human inadequacy against unflinching fate, the anger that this can be generated in the heart and soul when intense lyricism has been experienced, lost and then remembered with yearning. Beethoven for me requires what one might term the condiments of human imperfection, some temperamental roughness and not classical perfection.

This tougher, more masculine and intellectual approach became clear in the theme and six variations, each with a different character and partly contrapuntal texture, contained within the final movement Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo. The writing veers between moments of lyrical cantabile and the severely declamatory. The driving rhythmic energy of the fifth variation gives the impression, at least to begin with, of a complex, many-voiced chorale-like fugue. Son built an eloquent conclusion from a peak of powerful armour that resolved into quiet resignation at the conclusion. Beethoven’s approach to the variation form at the conclusion is far freer here than in his previous sonatas.

INTERMISSION

Fryderyk Chopin (1810‒1849)

|

| The Pleyel pianino at Valldemossa on which Chopin may have composed the C minor polonaise Op.40 No.2 |

Polonaise in C minor, Op. 40 No. 2 (1838–1839)

Son adopted a noble, tragic tempo in this great polonaise with in the Trio, a tragic and sublime, nostalgic sung cantilena. Cruel and brutal destiny hovers overs it and reality erupts once again to destroy the dream.

The polonaise is believed to have been composed in the dark atmosphere of the Carthusian monastery in Valldemossa. It would be difficult to find an alternative to the definition advanced by the writer, historian and musicologist Ferdynand Hoesick who wrote of the ‘gloomy mood’ that emanates from this music, of its melancholy and ‘tragic loftiness’.

Dedicated to Julian Fontana, Chopin wrote: ‘You have an answer to your honest and genuine letter in the second Polonaise. It’s not my fault that I’m like that poisonous mushroom […] I know I’ve been of no use to anyone – but then I’ve been of precious little use to myself’.

4 Mazurkas, Op. 24 (1833–1835)

G minor

C major

A flat major

B flat minor

Waltz in F minor, Op. 70 No. 2 (1841–1842)

Waltz in A minor, Op. posth. (1847–1849)

Waltz in A flat major, Op. 34 No. 1 (1835)

3 Ecossaises, Op. 72 (1829–1830)

D major

G major

D flat major

I could of course examine the performance of each in turn but of the performance of these works of Chopin I am left with absolutely nothing left to say. They seemed to me to express most of what I deeply feel concerning the music of Chopin in his Waltzes, Mazurkas and the sheer civilized charm and grace in his performance of the three Ecossaises.

Tarantella in A flat major, Op. 43 (1841)

|

| Dancing the Tarantella |

'I hope I’ll not write anything worse in a hurry’ – Chopin’s rather unflattering assessment of the Tarantella. Shortly after arriving in Nohant, Chopin wrote to Julian Fontana with the manuscript of the Tarantella (to be copied): ‘Take a look at the Recueil of Rossini songs […] where the Tarantella (en la) appears. I don’t know if it was written in 6/8 or 2/8. Both versions are in use, but I’d prefer it to be like the Rossini’

It did have some feeling of frenzy from the growing effects of the poisonous tarantula bite but for me lacked the characteristic joyfulness and gaiety of the Italian dance. I thought Son could have given us a more convincing rhythmic account of the victim of a poisonous spider bite (by the Tarantula) and the growth of the insidious, destructive chemical circulating in the blood. Traditionally the victim became well and truly beside himself, increasingly and madly so by the triumphant conclusion.

Polonaise in A flat major, Op. 53

This performance of the famous work was in many degrees faultless in its majestic nobility and fierce resentful anger. It was clearly the result of the accumulation of many, many years of intimate familiarity with the score, the performance, the teaching, the associative moods and imagery as well as the hearing of this masterpiece (in the espaces imaginaires). Incontrovertibly a political and musical revolutionary demonstration against invasion, territorial hegemony and brutal invasion of one's homeland. More appropriate now than in times of peace and a fine choice by Son to conclude, expressing human significance on many levels of deep musical association.

MONDAY

8 AUGUST 2022

CHOPIN MANOR 4.00 PM

Piano recital

DMYTRO CHONI

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

2 Rhapsodies, Op. 79 (1879)

No. 1 in B minor

No. 2 in G minor

Brahms wrote these attractive Rhapsodies in his maturity during his summer stay on the shores of the attractive Lake Wörthersee in Austria, Carinthia's largest lake. I felt the performance spoilt by too exaggerated dynamic contrasts - a fault in so many of the young prize-winners one hears today. This could be a result of the relatively small internal volume of the dworek.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

Étude in A minor, Op. 25 No. 11 (1835–1837)

A highly accomplished and promising performance from a young pianist with great future potential.

Ferenc Liszt (1811–1886)

Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata S. 161/7 (1849)

INTERMISSION

Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fût (Images II) (1907)

He accomplished a beautiful impressionistic 'image' of this painting 'And the moon descends on the temple that was...'

L’Isle joyeuse (1904)

|

| The Jersey coastline |

L'Isle joyeuse written on the island of Jersey when in a state of heightened emotion - the composer was joyfully embracing a passionate love affair in the summer of 1904 with Emma Bardac, the wife of a rich and prominent banker. His wife, 'Lilly' attempted suicide after Debussy wrote to her telling her the marriage was over. The ensuing scandal was to alienate Debussy from many of his friends, whilst Bardac was disowned by her family. They were eventually married in 1908. Much of La Mer was written on the island. Choni gave us an impressionistic account of the pieces, maintaining an attractive quality of a summer afternoon's improvisation but also passionate. The expression of the dynamic expression of sensual joy was youthfully impressive!

|

| Debussy and Emma Bardac on Jersey |

Valentin Silvestrov (born 1937)

3 Bagatelles, Op. 1 (2005)

Allegretto

I found this a charming, sensitive rather minimalist post-modern piece by the Ukrainian composer.

Moderato

A darker contrast here, but similar in its simplicity

Moderato

I imagined in this charming lyrical work, sentimental poetry in countryside, reclining on a rug in sunny summer pastures, in love with a delightful lady

Alberto Ginastera (1916–1983)

|

| A painting by Diego Dayer, born Argentina 1979 |

Sonata No. 1, Op. 22 (1952)

Alberto Ginastera was commissioned by the Carnegie Institute and the Pennsylvania College for Women to write a piano sonata for the Pittsburgh International Contemporary Music Festival. Ginastera’s intention for the piece was to capture the spirit of Argentine folk music without relying on explicit quotations from existing folk songs.

Allegro marcato

I found this movement exciting but rather too long and unrelenting in its forceful rhythmic projection

Presto misterioso

I really did not hear a great deal of what OI might consider 'mysterious' in any conventional sense.

Adagio molto appasionato

Here was contained Latin passion, but the passions of the dreaming night. Somnambulistic rather after all passion spent

Ruvido ed ostinato

Percussively quite unsettled

Encores:

An absolutely delightful Soiree de Vienne Concert Paraphrase after Johann Strauss Op.56 by Arthur Grünfeld (1852-1924)

Valentin Silvestrov Bagatelle 1 XIII/II

A most varied and interesting programme that is showing great promise as a discriminating musician and pianist

|

| An original 17th century door-case in Duszniki Zdroj |

Masterclass Aleksander Gavrylyuk

9.30 am Monday August 8th 2022

|

| Anna Golka who provides the brilliant, indispensable simultaneous translation from professorial musicological English into Polish at the Duszniki Masterclasses The session on 8th August began with Julia Lozowska working with Prof. Gavrylyuk on the formidable Brahms Variations on a Theme of Paganini Op.35. he spoke of the importance of the 'inner beauty' of the work, the inner process and filling the internal spaces with inner energy. He indicated there was always a purpose behind the music and one must envisage from a space at the beginning into which the piece moves. He emphasized the electricity which lies behind the notes and referred to 'a restless search for the light'. |

|

| Julia Lozowska working with Prof. Gavrylyuk on the Brahms Variations on a Theme of Paganini Op.35 |

|

| Pedalling the Brahms Variations on a Theme of Paganini Op.35 |

|

| Prof. Gavrylyuk working with Jozef Domzal on the Chopin Polonaise-Fantaisie Op.61 |

|

| Elucidating the function of the muscles of the thumb and their vital role |

|

| 'Allow the music to lead the process rather than imposing your personality upon it. You should be the conduit for the music.' |

|

Prof Gavrylyuk with Aleksandra Dębek Dealing with the so-called 'Raindrop' Prelude Op.28 No.15 he referred to the many and varied ways of opening this extraordinarily famous work. He did not refer to the fraught situation of its composition in Valldemossa, a haunting monastery he resided in with George Sand. The concentration was mainly on 'arches of sound', melodic line and how in performance the more simple the melody the more difficult it is to play with such exposed subtlety. Again concentrating on physical aspects, he demonstrated how to place arm weight on the note you wish to emphasize, where the other notes become weightless. At one point, he played the LH and she played the RH and slower to hear the internal details. |

SUNDAY 7 AUGUST 2022

CHOPIN MANOR 8.00 PM

Piano duo

LUCAS & ARTHUR JUSSEN

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Sonata for 2 pianos in D major, K.448 (1781)

A great shout greeted their entrance onto the stage - familiarity and anticipation for great entertainment in store.

Allegro con spirito

This rather rare work was composed in the galant style when Mozart was only 25 - close to the age of these two young, lively Dutchmen. Certainly this was a spirited beginning which continued with exuberant energy. I could not help imagining that Mozart may well have loved the irresistible forward impetus of this movement. A fine co-ordinated sound and quite uncanny, almost symbiotic ability, to combine their forces in perfect cohesion.

Andante

A charming and civilized consolation to the travails of existence in 2022. Once more a feeling of perfect synchronization on the levels of sound and feeling, although the brothers are not twins. the phrasing was particularly revealing of musical meaning.

Allegro molto

A lively movement once again with reminiscences of Mozart's Rondo alla Turca

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)

Rondo for piano 4 hands (Grande Rondeau)

in A major, D.951 (1828)

|

| A Schubertiade (1897) by Julius Schmid |

This work from 1828 was considered by Alfred Einstein in his book Schubert as 'the apotheosis of all Schubert's compositions for four hands.' (p.282). Compositions for four hands are by their very nature considered sociable in a cultural context. The Schubertiade was a social event perfectly compatible with piano music for four hands. During Schubert's lifetime, these events were generally informal, unadvertised gatherings, held at private homes.The work has also been described as 'leisurely' and 'easygoing' and this duo communicated this almost carefree and gracious attitude within the music in their remarkably charismatic social communication. Schubertian yearning makes a subterranean appearance.

|

| Franz Schubert (1797-1828) |

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

Rondo in C major for 2 pianos, Op. 73 (1828)

INTERMISSION

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

6 Épigraphes Antiques for piano 4 hand (1914–1915)

|

Background: Claude Debussy standing in the drawing room at Pierre Louÿs house

National Library of France,

RES-VM EST-3 (11)

|

Macabre Letter: Pierre Louys to Claude Debussy, May 1901 National Library of France, Music Department, NLA-45 (53) |

I was not familiar with this work but on such a sociable moment of four-handed compositions I felt I must take advantage and listened carefully. This suite was Debussy's only completed composition in 1914. A great deal of the music is taken from the musical accompaniments he had written in 1901 for his friend Pierre Louÿs (1870–1925). He was a French poet and writer, most renowned for lesbian and classical themes in some of his writings. He is known as a writer who sought to 'express pagan sensuality with stylistic perfection'

|

| One of the less erotic photographs taken by Pierre Louÿs (1870–1925) |

Pour invoquer Pan, dieu du vent d'été (To invoke Pan, god of the summer wind)

Played with a beautiful and affecting lyricism

Pour un tombeau sans nom (For a nameless tomb)

Dark and impressionistic lugubriousness

Pour que la nuit soit propice (In order that the night be propitious)

They conjured up haunting, internal, imaginative visions of the night

Pour la danseuse aux crotales (For the dancer with crotales)

This was highly energetic playing and the duo created the image of dancers clashing with their small brass percussion discs (about 10 cm in diameter)

Pour l'égyptienne (For the Egyptian woman)

I felt a certain stasis and mystery of the sphinx in their performance - rather an inaccessible female quality in the Egypt of the day

Pour remercier la pluie au matin (To thank the morning rain)

With their astounding virtuosity they recreated the memory and sound of the morning rain that Debussy composed so realistically. Quite affecting if one loves the natural world to distraction.

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

La valse version for 2 pianos

|

COURT BALL AT THE HOFBURG A waltz in the public ballroom of the Imperial Palace, Vienna. Watercolor by Wilhelm Gause 1900. Emperor Francis Joseph is on the far right |

Diaghilev had requested a four-hand reduction of the original orchestral score. Reports say that Stravinsky when he heard Ravel perform this with Marcelle Meyer in this version, he quietly left the room without a word so amazed was he. Ravel however would not admit to the work being an expression of the profound disillusionment in Europe following the immeasurable human losses and cruel maiming of the Great War. However one must recall in Thomas Mann’s Dr. Faustus that the composer Adrian Leverkühn, although isolated from the clamour and destruction of the cannons of war, composed the most profound expression of it in his composition Apocalypsis cum Figuris by a type of metaphysical osmosis. Ravel’s note to the score gives one an insight to his intentions:

Ravel described his composition as a ‘whirl of destiny’ – his concept was that the work impressionistically begins with clouds that slowly disperse to reveal a whiling crowd of dancers in the Imperial Court of Vienna in 1855. The Houston Symphony Orchestra programme note for the orchestral version performed in 2018 poses the question: Is this a Dance of Death or Delight ? I feel the question encapsulates perfectly the ambiguity inherent in this disturbing work. A composer can sometimes be a barometer that unconsciously registers the movements of history.

The duo opened this work with a sound that was inescapably an ominous premonition of war. The two concert grands began to sound like distant and often not so distant cannons. The recalled waltz rhythm of the beginning of this trance was idiomatic, stylish and understated. The sound created by this remarkable duo is rich and full and yet not breaking through the sound ceiling of their instruments (although the ceiling of the dworek may well have suffered stress!).

The sense of threat was ever present as the overwhelming energy of the whirling and bursts of light from the chandeliers built into a sound edifice, the like of which was like nothing I have ever heard in my life. The glissandos that sliced through the monumental, energetic sound towards the conclusion was like the merciless cut of a Polish sabre on horseback. A rhapsodic ending with cannons was breathtaking in the extreme.

The tumultuous standing ovation and cheers gave rise to three appropriate encores by Bizet from his piece for four hands entitled Jeux D'enfants. : La Toupie (The Spinning Top) La Poupée (The Doll) and Le Bal (The Ball),

This was followed by I think their own arrangement of classical standard melodies we could all recognize beneath the ornamentation. Finally a Siloti/Bach transcription.

A remarkable and memorable evening of astonishing natural keyboard gifts. Classical music performed for the sheer musical entertainment value and wish to give unadulterated pleasure to the audience without the sacrifice of interpretative musicality of a high order.

SUNDAY, 7 AUGUST

CHOPIN MANOR 4.00 PM

Piano recital

JUAN PÉREZ FLORISTÁN

First Prize at the 16th Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition Tel Aviv 2021

Fryderyk Chopin (1810‒1849)

24 Preludes, Op. 28 (1838–1839)

Even if

Chopin had not written anything but the preludes, he would have deserved

immortality anyway.

Anton Rubinstein

These

poetic preludes are similar to those of a great contemporary poet that rock the

soul in golden dreams and raise it to ideal regions.

Franz Liszt

Each

of them is a prelude to a meditation […] Music that eludes the world of matter

and allows us to free ourselves from it.

André Gide

In January 1839, after his Pleyel pianino had arrived from Paris, Chopin wrote to Julian Fontana ‘You’ll soon receive the Preludes and the Ballade’. And a few days after, when sending the manuscript of the Preludes: ‘In a couple of weeks, you’ll receive the Ballade, Polonaises and Scherzo.' So their conception took place in the atmosphere of a haunted monastery, threatened by untamed nature.

It would of course have been impossible for Chopin to have ever considered performing this complete radical cycle in his own musical and cultural environment (not least because of the brevity of many of the pieces). It is unlikely ever to have even occurred to him to do this, the way programmes were designed piecemeal at the time. I tend to feel the performance of them as a cycle is of course possible but not entirely justified. In some of his programmes and others of the period, a few preludes are scattered randomly through them like diamond dust. Each piece contains within it entire worlds and destinies of the human spirit and deserves individual attention rather than being a brick in a monumental edifice.

It is now well established by

structuralists and Bach scholars as a complete and symmetrical work, a

masterpiece of integrated yet unrelated ‘fragments’ (in the late eighteenth and

early nineteenth century sense of that aesthetic term). Each prelude can of

course stand on its own as a perfect miniature landscape of emotional feeling

and tonal climate. But ‘Why Preludes? Preludes to what?’ André

Gide asked rather gratuitously. One possible explanation is that the idea

of 'preluding' as an improvisational activity in the same key

for a short time before a large keyboard work was to be performed was well

established in Chopin's day but has been abandoned in modern times.

The Preludes surely extend the prescient Chopin remark 'I indicate, it's up to the listener to complete the picture'.

I felt Floristán gave us a fine, virtuoso pianistic account of this popular cycle. He had clearly conceived of them as an integrated group of emotional landscapes. However, for me rather predictably straightforward without what one might term, an 'individual voice'. I will make only a brief comment on some of them as an analysis in detail of all might try your patience although each masterpiece deserves the deepest attention. There was insufficient hint of the haunted nature of some preludes, haunted by the ghosts of Valldemossa and the demons that inhabit our lives. The metaphysical underside of these works, the dark realities and contrasts in emotional turbulence were somewhat left untouched by the brilliant playing.

No. 1 in C major

No. 2 in A minor - few pianists plumb the utter despair in the face of the great reality of death, ultimately faced alone by each of us, that suffuses this spare, desolate masterpiece. Floristán was unsettling but ...

No. 3 in G major - a joyful respite

No. 4 in E minor No. 5 in D major No. 6 in B minor No. 7 in A major - all satisfyingly performed but I was yearning for more individuality, taking me beyond the printed score

No. 8 in F sharp minor - a brilliant account of this prelude

No. 9 in E major No. 10 in C sharp minor No. 11 in B major No. 12 in G sharp minor

No. 13 in F sharp major - the bel canto was alluring and beautiful

No. 14 in E flat minor No. 15 in D flat major No. 16 in B flat minor No. 17 in A flat major No. 18 in F minor

No. 19 in E flat major No. 20 in C minor No. 21 in B flat major No. 22 in G minor No. 23 in F major

No. 24 in D minor - I think with this work, the heavy hammer of irreversible destiny falls on deeply disturbed emotions that hinge on an awareness and premonition of death. To achieve this requires a particular vision not given to many, but a profound thought preoccupying Chopin.

INTERMISSION

Ferenc Liszt (1811–1886)

Années de Pèlerinage. Deuxième années. "Italie" S. 161 (1838–1839)

Sposalizio

|

Sposalizio della Vergine (The Marriage of the Virgin) Raphael 1504 |

Franz Liszt composed Sposalizio, which translates to Marriage in Italian, after being inspired by Raphael's painting the Marriage of the Virgin of 1504. Beginning Andante with the indication dolce the work develops into a variety of wedding march which concludes in a rand climax in difficult octaves. As too often with this pianist (and others) the relatively small Dworek found it difficult to accommodate to the almost oppressive dynamic inflation.

Il pensieroso

Michelangelo LORENZO DE' MEDICI Church of S. Lorenzo, Florence |

This work (1838-1839) was inspired by the idealized introspective and melancholy Michelangelo sculpture that the Italian carved for the tombstone of Lorenzo de Medici, Duke of Urbino. The sculpture inspired many great artists over the centuries from the epic poem by John Milton to the British/American Painter Thomas Cole's painting Il pensieroso dating from 1845. Michelangelo depicts Lorenzo as an intellectual man lost in deep in thought. The seriousness of the sculpture gives rise to a rather gloomy musical work. I remained unsure why Floristán chose this work for his recital.

Richard Wagner (1813–1883) /Ferenc Liszt (1811–1886)

Isoldes Liebestod, S. 447

|

| Rogelio de Egusquiza (1845-1915) Tristan and Iseult (1910) This Spanish painter, known for his friendship with Richard Wagner, helped make his works familiar in Spain |

One must not forget the constraints of instruments that brought about such transcriptions and the extraordinary service the selfless Liszt performed for keyboard players in the nineteenth century who were without ready access to an organ or the services of an orchestra. We are indeed richly endowed today and tend to forget this when maligning the great Ferenc for his generous transcriptions of everything under the sun.

I felt this was a rather exaggerated musical performance by the Spanish pianist on the level of the psyche, embracing the fulfillment or 'peaceful release' offered by death, carried unresisting on the cresting wave of metaphysical and passionate love. Certainly the incandescent passions and travails of Latin Spanish love were well in evidence. The building of the erotic curve in a smooth, sensually rising line to the orgasmic climacteric, the apotheosis of the metaphysical symbiosis of love/death that Wagner embraces, is a tremendously demanding pianistic task to express, to discipline and to communicate effectively as he managed to do.

Wagner's debt to the harmonic adventurism of Liszt, the Tristan chord, is never in doubt to my mind. The work is a musical and personal challenge to depict this merging of the lovers in death, situated predominantly and 'deep darkly' in the mind of Wagner. The contrasts Floristán extracted and expressed were rather too extreme in range for me but perhaps after all is said and done, the heat of 'Spanish love', its transfiguration and expression through music depends on the filter of personal experience.

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)

Wanderer Fantasy, Op. 15, D.760 (1822)

Allegro con fuoco ma non troppo

Adagio

Presto

Allegro

This work the composer based on his song Der Wanderer. This was a competent account of the Fantasy but I yearned for a more melodic and expressive legato line on some occasions. He stayed pretty well at the same dynamic which I found rather tiring. So many opportunities for poetry and expressiveness were missed and the conception of the work came across to me at least as rather prosaic.

I felt he Floristán unfortunately had limited understanding of this work. Much of his playing could be described in the words of C.P.E Bach in his Versuch über die wahre Art das Klavier zu spielen 1753 (Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments)

‘They overwhelm our hearing without satisfying it and stun the mind without moving it.’

The opening indicated he would be approaching this remarkably variegated work as purely a virtuoso piano piece. The dynamics only occasionally fell below forte or fortissimo except in the more lyrical, reflective central sections with rather rushed phrasing. However the ‘interpretation’, such as it was, for me displayed extraordinarily limited understanding of Schubert’s intentions in this piece – the operatic nature of ‘The Wanderer’ passing thorough varied landscapes and the joyful and bitter experiences of life on his great journey through it. He wrote the work in 1822 only six years before his premature death. The work is surely a keyboard version of what might have been another great Schubert song cycle. The main theme in a hardly festive C-sharp minor actually taken from his song Der Wanderer. Perhaps far more background research on such a great work should be done before performance.

I once heard the great pianist Alexander Melnikov at the Chopin i jego Europa Festival in Warsaw give a brilliant account of this work on a Conrad Graf piano which illuminated the shifting landscape and fluctuating moods in an unprecedented manner perfectly suited to Schubert. Conrad Graf (1782-1851) was an Austrian-German piano maker whose instruments were used by Beethoven, Chopin, Schubert and Clara Schumann among others. They were capable of extraordinary sonority and special effects.

Schubert once wrote 'Happiness is where you are not...' and explaining that the 'Romantic soul is never happy where he is...' Schubert had an inferiority complex concerning Beethoven. The work is marked by grace, grandeur and nobility. At times unsettled, it would calm into glorious song full of human emotion. For me there is far too much use of this work as a showy virtuosic account.

Encores:

The Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983)

Two Danzas Argentinas (Argentine Dances) Op. 2 from a set of three dances for solo piano written in 1937

No: 2 Danza de la moza donosa (Dance of the Donosa Girl) and No: 3 Danza del gaucho matrero (Dance of the Outlaw Cowboy) has directions such as furiosamente (furiously), violente (violent), mordento (biting), and salvaggio (wild). Here Ginastera left us in no doubt as how to perform this third dance.

Both were splendidly performed, No:3 simply astounding in its rhythmic insistence.

SATURDAY, 6 AUGUST 2022

CHOPIN MANOR 8.00 PM

Chamber concert

RAFAŁ BLECHACZ (piano)

BOMSORI KIM (violin)

Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

Violin sonata in G minor (1917)

Claude Debussy (1862–1918) was already suffering with the cancer which prematurely ended his life, when he began to compose his Violin Sonata in G minor, L140. He began to sketch the work in 1916 and completed it the following year. It was to be his final composition. He wrote rather self-effacingly 'It represents an example of what may be produced by a sick man in time of war’ In this sonata he wished to be rather anti-German by emphasizing his national background by signing the score ‘Claude Debussy—musicien français’.

The first moment of sound of Bomsori Kim's magnificent violin (a 1774 Giovanni Battista Guadagnini instrument) revealed a profound richness of tone that can imitate a viola. The tension between the body of this brilliant South Korean violinist and her instrument produces a sound that was sheer musical magic.

The violinist’s chosen repertoire reflects her desire to communicate with her audiences through her instrument’s expressive voice: 'I’m not a loud person – I usually don’t talk much in everyday life,” she says. “But that’s why I love playing the violin, because I can speak and communicate through music. I’ve loved singing and ballet since I was a small child and am always moved by hearing voices and watching dancers. I wanted to bring that special spirit of poetry and drama to listeners through my instrument, which can sing freely in these wonderful pieces.' (DG)

Allegro vivo

Ardent playing by both artists with superb musical co-ordination. This music was clearly deeply experienced by the players in a work that suffuses melancholic nostalgia.

Intermède: fantasque et léger

The awful old clouds are dispersed in this movement that sings of the joys of love and yearning.

Finale très animé

The earlier mood returns which surprisingly develops into to an ecstatic conclusion with perfectly co-ordinated phrasing and breathing. These are artists who understand each other intimately in the climate of music. A mood of optimism prevailed despite Debussy’s own tragic health circumstances.

Karol Szymanowski (1882–1937)

|

| Szymanowski by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz |

Sonata in D minor, Op. 9 (1904)

Allegro Moderato

Andantino Tranquillo e Dolce

Allegro Molto, quasi Presto

This work was first performed in Warsaw by two renowned musicians, the violinist Paweł Kochański and pianist Artur Rubinstein, on 3rd April 1909. It is the work of a young man but his unique voice is already manifest. He dedicated it to his school friend Bronisław Gromadzki who was an amateur violinist. The Allegro moderato was played by both artists in an affectingly expressive, ardent yearning with rich and eloquent tone colour from the violin and the intense manner young hearts express in lyrical love and passion. There are two themes: the virtuoso element increasing expressively to con passione, and a lyrical, dolcissimo, which at times had the qualities of a dream.

The Andantino tranquillo e dolce is the beating heart of this work. The artists were intensely lyrical and explored contrasting colours and timbres with the violin pizzicato and the piano staccato. Such a yearning for love's consummation lies within Szymanowski, searching for the stars and the night sky of ecstatic oblivion.

The authority

on the music of Szymanowski Tadeusz A. Zieliński wrote of this work:

‘…as such it must be the greatest instrumental work of Szymanowski’s early period. Only [its] unfamiliarity to musicians accounts for the fact that this wonderful ‘poem’ in A major did not become a famous and favourite item in violinists’ repertoires’.

The Finale. Allegro molto, quasi presto supported some fine and remarkable rhapsodic, highly emotional themes. The phrasing of this violinist and pianist was both sensitive and passionate, which made this virtuoso ensemble absolutely captivating. There was an extraordinary musical intimacy and deep communication evidently present here as the work developed rhapsodically. Szymanowski himself was eventually able to describe the Sonata as 'a thing popular in every aspect.'

INTERMISSION

Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924)

|

| The young Gabriel Fauré |

Sonata No. 1 in A major for violin and piano, Op. 13 (1875–1876)

Allegro molto

Andante

Scherzo: Allegro vivo

Finale: Allegro quasi presto

In 1872 Camille Saint-Saëns, Fauré’s former piano teacher, introduced him to the great singer Pauline Viardot (so close to Chopin in friendship) and her musical family. Fauré went so far as to dedicate songs to her and fell in love with her daughter Marianne (who would break off their engagementafter a short time together). Fauré dedicated his First Violin Sonata to her son, the violinist and composer Paul Viardot.

Marie Tayau, who established one of the first all-female string quartets, gave the premiere in January 1877, with Fauré at the piano. 'The sonata had more of a success this evening than I could ever have hoped for' Fauré wrote to a friend. 'Saint-Saëns said that he felt that sadness that mothers feel when they see their children are too grown up to need them any more!... Mlle. Tayau’s performance was impeccable.'

Saint-Saëns observed: 'In this sonata you can find everything to tempt a gourmet: new forms, excellent modulations, unusual tone colors, and the use of unexpected rhythms,' he wrote. 'And a magic floats above everything, encompassing the whole work, causing the crowd of usual listeners to accept the unimagined audacity as something quite normal. With this work Monsieur Fauré takes his place among the masters.' (quotations courtesy of the LA Philharmonic)

Kim and Blechacz expressed the ardent melodies of the opening Allegro molto movement with refined and urgent intensity of sound to animate these glorious melodies and transport one into the poetic world of French poetry. The sound of Kim's violin and her profound musicality was simply enthralling both sensually and spiritually. There was much rich, animated musical 'conversation' between these two artists. The romantic theme of the Barcarolle of the Andante was replete with heartfelt love or was this just my own romantic temperament. The vivacious Scherzo: Allegro vivo was fabulously light and spectacular with Kim singing on her glorious violin in the lyrical section. Both artists evidenced highly virtuosic playing to take us into the light, flying, bustling and gliding in the true meaning of the word scherzo. Rhythmic invention, shifting key, colour and metre like a shaken kaleidoscope. Then the yearning, profoundly ardent theme of the Finale: Allegro quasi presto which revealed the deep musical commitment between these two great artists, their ability to articulate the pregnant harmonic functions and transitions, the characteristically French passion lying in wait within the music.

The encores were also deeply moving for me. Two pieces of Chopin arranged persuasively for violin and piano. At first the Nocturne in E-flat major Op.9 No.2 which exploited the ample mahogany tone of her violin. Then such a stylish Syncopation by Fritz Kreisler and finally a tear inducing Chopin Nocturne No. 20 in C♯ minor, Op. posth., Lento con gran espressione.

A most memorable and rewarding concert by true artists who elevated their musical programme to the heights.

SATURDAY, 6 AUGUST 2022

CHOPIN MANOR 4.00 PM

Piano recital

JONATHAN FOURNEL First Prize at the

Queen Elizabeth Competition in Brussels 2021

Fryderyk Chopin (1810‒1849)

Nocturne in B major, Op. 62, No. 1 (1846)

.jpg) |

| A tuberose at night |

‘What is most exquisite and most individual in Chopin’s art, wherein it differs most wonderfully from all others,’ noted André Gide ‘I see in just that non-interruption of the phrase; the insensible, the imperceptible gliding from one melodic proposition to another, which leaves or gives to a number of his compositions the fluid appearance of streams.’ This is a characteristic of Chopin during the 1840s, in his last, reflective, post-Romantic phase.

The Paris

critic Hippolyte Barbedette, one of Chopin’s first biographers, wrote of

Chopin's Nocturnes ‘are perhaps his greatest claim to fame; they are

his most perfect works’. That is how they were seen in Paris during

the mid nineteenth century. Barbedette explained the reason for their success

as follows: ‘That loftiness of ideas, purity of form and almost

invariably that stamp of dreamy melancholy’.

Interestingly in the Anglo-Saxon world, the B major Nocturne has been given the name of an exotic greenhouse flower: ‘Tuberose’. The American art, book, music, and theatre critic James Huneker explains why: ‘the chief tune has charm, a fruity charm’, and its return in the reprise ‘is faint with a sick, rich odor’.

The Polish pedagogue and Chopin philosopher Tomaszewski writes of the opening 'The Nocturne in B major opens with what might be described as a bard’s striking of the strings.' For me Fournel opened in a rather mannered style and did not penetrate sufficiently the sensitivity that the night poem deserves, its hesitant uncertainty. He failed to create a sufficiently hypnotic poetic atmosphere of the decorated bel canto song, surely one of the hallmarks of this Nocturne. There is great variety in the mood and writing of this rather untypical Chopin Nocturne. I felt occasionally his phrasing and approach. especially the opening, verged on the cultivated but this is always difficult to judge accurately and objectively in works that rely on such deep emotive expression.

Sonata in B minor, Op. 58 (1844)

Allegro maestoso

Scherzo molto vivace

Largo

Finale. Presto non tanto

Here we have one of the greatest masterpieces in the canon of Western piano music.

The opening Allegro maestoso was dramatic but rather too declamatory and overtly 'pianistic' without sufficient musically expressive dynamic variation, the play of thought. His fortes tended to be harsh and dominant on the Shigeru Kawai grand piano in this relatively small volume Dworek salon. Fournel was revealed as not going to be a particularly poetic, philosophical or lyrical interpreter of this magnificent work. One should feel that Chopin was embracing the cusp of Romanticism, yet at the same time hearkening back to classical restraint - le climat de Chopin as his favourite pupil Marcelina Czartoryska described it. The Trio did have a degree of cantabile that made the piano sing. However, the Scherzo was rather disappointing in its over-straightforward phrasing without enough of that Mendelssohnian atmosphere of fairy lightness that I feel it needs. The Trio again however displayed some warm Chopin cantabile.

The transition to the Largo was not sufficiently expressive in the opening with premonitions of what is to come in this extraordinary introspective dream-poem. Here we begin an exquisite extended nocturne-like musical voyage taken through a night of meditation and inturned thought. This great musical narrative of extended and challenging harmonic structure must be presented as a poem of the reflective heart and spirit. I felt Fournel could have brought a more contemplative quality, created a more mellifluous dream world of searching, yet retaining a sense of directional focus in the wandering harmonic transitions. This is very difficult to achieve in this movement which requires rare musical and personal maturity.

The Finale. Presto ma non tanto for me failed to produce that irresistible headlong rush with the slowish tempo he adopted. Fournel approached this movement as rather a virtuoso piano work than a rhapsodic narrative Ballade in character. Again dynamic variation of an expressive kind was rather absent. Throughout the sonata, although of course finely played with great virtuosity (as the enthusiastic reception of the audience testified), I kept wondering what Fournel was trying to tell me about this work with any individual sense and voice.

Tomaszewski again who cannot be bettered:

Thereafter, in a constant Presto (ma non troppo) tempo and with the expression of emotional perturbation (agitato), this frenzied, electrifying music, inspired (perhaps) by the finale of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony…’

The pianist must further explore what is buried within the contextual poetry of the musical work (the printed notation is only the roughest of guides to the composer's true creative conception lodged in his brain and inner sound world). Then his next task is to create a perception of this in us the listeners, allowing us to perceive a closer approximation of the composer's true expressive intentions. Fournel's keyboard virtuosity, although spectacular, even astonishing, sacrifices much of Chopin's classicism and restraint on the altar of high Romanticism. A deeper sense and understanding of the structure of the sonata would have assisted in this.

INTERMISSION

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Op. 5 (1853)

Brahms composed this mighty sonata when he was barely 20 and when the sonata form itself was considered rather an outmoded genre. Of course Brahms idolized Beethoven and the personal expressiveness of his sonatas and perhaps was influenced by these grand conceptions.

|

| The young Brahms |

The sonata is unconventionally in 5 movements.

- Allegro maestoso

- Andante espressivo

- Scherzo. Allegro energico - Trio

- Intermezzo. Andante molto

- Finale. Allegro moderato ma rubato

For the magnificent, noble opening, Fournel abided by the Brahms direction Allegro maestoso which was ‘majestic’ indeed, symphonic and orchestral as was the composer's intention. However one must remember this is a true Allegro rather than the Adagio maestoso which Fournel tended to adopt without sufficient dynamic variation to build this great cathedral of inspiration and grandeur. Fournel presented the fortissimo chords that cover such a wide range of the keyboard with some control and discipline but was emotionally tempted to move into the realms of harsh sound almost breaking through the sound ceiling of the instrument in intensity. I felt he rather overemphasized the dynamics. The essentially Romantic spirit of the sonata should be fused into a classical edifice, the architecture of which is truly awesome to behold over the approximately 40 minutes duration.

From the divine sensitivity of the Andante expressivo it was clear Fournel only partially understood the slow movement as one of the greatest declarations of poetic love in music, the two lyrical themes merging symbolically into a passionate expression of sensual rapture. Brahms yearning in youth for the impossible love of the brilliant Clara Schumann ? I was yearning for more poetic variety of tone and touch indicated by the distinctly Brahmsian tonal palette of the sonata. The Scherzo again was rather too emphatic to express fully this dark waltz that is so musical and dramatic.

Brahms gave the Intermezzo the title ‘Rückblick‘ which literally means ‘Remembrance’ which winds into a virtuosic and triumphant Finale of the greatest majesty. Here I felt the tempo of the rondo was rather too fast to allow my own emotions as a listener to grow organically in harmony with the music, rather than being imposed upon me by the pianist. I found it difficult to follow sufficiently the significant musical cryptogram that was a personal musical motto of his Hungarian violinist, conductor, teacher friend Joseph Joachim, the F–A–E theme, which stands for Frei aber einsam (free but lonely). The triumphal impact and nature of the virtuosic and rhapsodic harmonic close, of which Brahms was such a symphonic master, could have been more carefully and effectively cultivated in terms of tempo and dynamic variation and expressiveness.

Overall I felt Fournel has not yet developed that true nobility of the Brahmsian soul in his playing, that sufficient amplitude of dynamic expressiveness that is so difficult to achieve. His mastery of the notes and keyboard is clear but the personal and musical maturity hopefully will come. Brahms controls the nature of silence expressively to imbue this great premonitary piano work with the profound musical meaning of his essentially late Romantic intentions. Fournel's sense of structure was not well enough established to completely create this miraculous monumental construction in sound, a Chartres cathedral hewn in stone.

As encores, a sensitive Bach 'Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring' Jesus bleibet meine Freude and the Bach/Siloti Prelude in B minor

First Prize at the 18th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw 2021

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

French Suite No.5 in G major, BWV 816 (1722)

Here was a case in point where Liu selected a restrained dynamic suitable for the type of small salon that would have accommodated such a refined work on the clavichord or harpsichord. I have not heard him perform the English Suites of Bach, but feel he would instinctively adopt a more robust tone for the more substantial writing.

He completely grasped the intimate nature of the elegant and graceful Bach French Suite No 5 in G minor BWV 816 written in the French taste. Yet for me despite the refinement of this performance, a truly idiomatic and instinctive grasp of the intimacy, affectation, allure and sheer seductive charm of the French/Italian tradition of the day (regarded as an ideal by Bach incidentally) escaped him a little - a very personal conviction of mine as a lover of the music of Francois Couperin which Bach knew.

Allemande

Light, and semi-detaché as this introductory dance should be. The opening was written for Bach's wife.

|

| The Allemande |

Courante

This characteristic 'flowing' movement usually followed the Allemande. The Baroque German composer, singer, writer and general polymath Johann Mattheson (1681-1764) in Der vollkommene Capellmeister (Hamburg, 1739) wrote rather affectingly of this dance '....chiefly characterized by the passion or mood of sweet expectation. For there is something heartfelt, something longing and also gratifying, in this melody: clearly music on which hopes are built.' Although Liu truly moved the piece like a glistening mountain stream, with fine LH polyphony counterpoint, it was more of an Italian corrente. But this merely is a quibble of tempo based on personal appreciation.

Sarabande

This rather melancholic yet gracefully reflective, stately French courtly dance (of Spanish origin) lies at the affecting heart of the entire suite. Liu gave this expressive position great significance.

Gavotte

This came as an absolutely delightful and elegant contrast to the Sarabande with eloquent LH counterpoint contrast

|

| The French Gavotte also known as the 'kissing dance' |

Bourrée

Of delightful symmetry, yet a dance quicker in tempo than the Gavotte

Loure

A rather slower introduction to the delightful Gigue that will conclude the work.

Gigue

Fryderyk Chopin (1810‒1849)

Ballade in F major, Op. 38 (1839)

Chopin was working on the F major Ballade in Majorca. In January 1839, after his Pleyel pianino had arrived from Paris, he wrote to Fontana ‘You’ll soon receive the Preludes and the Ballade’. And a few days after, when sending the manuscript of the Preludes: ‘In a couple of weeks, you’ll receive the Ballade, Polonaises and Scherzo.' So the conception took place in the atmosphere of a haunted monastery, threatened by untamed nature. Here was conceived the idea of contrasting a gentle and melodic siciliana with a demonic presto con fuoco – the music of those ‘impassioned episodes’, as Schumann referred to them.

|

| The 'Chopin monastery' at Valldemossa, Majorca |

Liu gave us a poetic, on occasion restrained yet passionate performance of the work that expressed the narrative of its imaginative drive and his conception of Chopin as a grand maître of the instrument. This has always struck me about Liu and many other young masters of the instrument. They produce interpretations that closely mirror the ideals of the physical and the powerful, ideal concepts of our own era, rather than 'the moving toyshop of the heart' as the 18th century English poet Alexander Pope observed.

The Leipzig encounter with Chopin Schumann experienced in 1840 is instructive. 'A new Chopin Ballade has appeared’, he noted in his diary. ‘It is dedicated to me and gives me greater joy than if I’d received an order from some ruler’. He remembered a conversation with Chopin: ‘At that time he also mentioned that certain poems of Mickiewicz had suggested his ballade to him.’ The operative word here is 'suggested' which precluded any confusing concept of programme music.

|

| Chopin often sat in George Sand's garden to compose. She was a keen horticulturalist as is evident in her garden at the west side of the house |

INTERMISSION

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

Ravel dedicated this work to the poet Léon-Paul Fargue.

Oiseaux tristes (Sad Birds)

Ferenc Liszt (1811–1886)

Réminiscences

de Don Juan,

S.418 (1841)

(Reminisces from Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni)

http://www.michael-moran.com/2013/07/68th-international-chopin-piano.html

http://www.michael-moran.com/2011/08/66th-duszniki-zdroj-international.html

http://www.michael-moran.com/2010/08/65th-duszniki-zdroj-international.html

In the time of the dreaded Coronavirus, the visit by this immortal composer to Duszniki Zdrój (then Bad Reinerz in Silesia) seems almost appropriate! Of course Chopin himself was no stranger to pandemics, as cholera took Paris twice by the throat during his time there.

If you wish to read about the pandemics that Chopin lived through in Paris, I have done some research:

Chopin sketched by Eliza Radziwill at Antonin en route to Duszniki Zdroj 1826. |

Duszniki as a treatment centre has not greatly changed. Tuberculosis has however thankfully disappeared. The Spa Park and the town nestle in the peaceful mountain river valley of the tumbling Bystrzyca Dusznicka. Fresh pine woods flourish on the slopes and the moist micro-climate is wonderfully refreshing. Carefully stepping invalids negotiate the shaded walks that radiate across the park between flowering shrubs, fountains and lawns.

Many famous artists visited Duszniki in the nineteenth century including the composer Felix Mendelssohn. In times past the regimented cures began at the ungodly hour of 6 a.m. when people gathered at the well heads. The waters at the Lau-Brunn (now the Pienawa Chopina or Chopin’s Spa) were dispensed by girls with jugs fastened to the ends of poles who also distributed gingerbread to take away the horrible taste (not surprisingly it was considered injurious to lean towards the spring and breathe in the carbon dioxide and methane exhalations).

Sviatoslav Richter (far left) on the steps of the Dworek Chopina at the 1965 Duszniki Zdroj Festival |

The soulful young Russian Igor Levit is deeply involved with the music of Schumann. He movingly reminded the audience of the genesis of the Geistervariationen (Ghost Variations) written when the composer was on the brink of suicide in a mental institution. After completing the final variation Schumann fell forever silent. The great Liszt super-virtuoso Janina Fialkowska, a true inheritor of the nineteenth century late Romantic school of pianism, courageously returned to the platform here after her career was brought to a dramatic and terrifying halt by the discovery of a tumour in her left arm. Daniil Trifonov utterly possessed by the spirit of Mephistopheles in the greatest performance of the Liszt Mephisto Waltz No:1 I have ever heard. The moments continue...

One remarkable late evening event of the festival is called Nokturn and takes place by candlelight. The audience in evening dress are seated at candlelit tables with wine. A learned Polish professor and Chopin specialist such as the wonderful Polish musicologist Professor Irena Poniatowska might draw our attention to this or that ‘deep’ musical aspect of the Chopin Preludes or perhaps the influence of Mozart on the composer. Sometimes it is a famous actor, music critic, or journalist. The pianists ‘illustrate’ and perform on Steinways atmospherically lit by flickering candelabra.

|

Introduction to the History of the Festival

The iron ore deposits of what was known as Bad Reinerz (now Duszniki Zdroj) and its surroundings have been exploited since the beginning of the 15th century. Protestant miners emigrated here during the religious turmoil of the Thirty Years War when mining was established at the end of the 17th century. A molten iron and a hammer mill was established in 1822 by Nathan Mendelssohn (an instrument maker). With his brother Joseph Mendelssohn's financial help he revived the mining industry. I have often wondered if it was at this mill that the the tragedy occurred for which Chopin gave his charity concert.

The commemorative plaque on the house |

Comments

Post a Comment