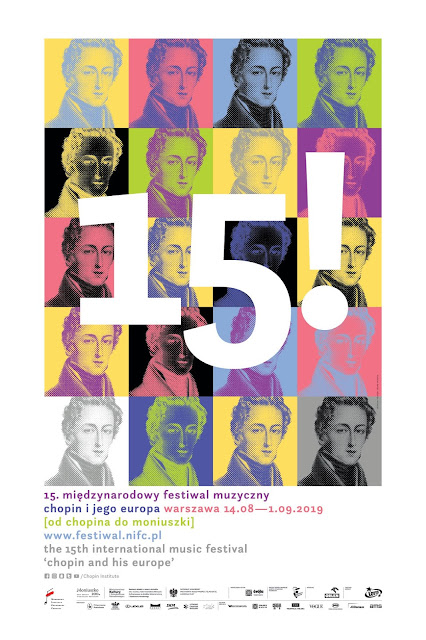

15th Chopin and His Europe Festival (Festiwalu Chopin i jego Europa) Warsaw, Poland 14 August - 1 September 2019 (2)

From Chopin to Moniuszko

All Photos Wojciech Grzedzinski

And so another fine edition of Chopin and His Europe (Chopin i jego Europa) concludes with a concert that was rather inspiring and certainly expressing optimistic signs for the future of orchestral music in Warsaw. Many fine concerts ahead!

31.08.19

https://michael-moran.org/2019/06/16/bach-court-composer-bach-festival-leipzig-14-june-23-june-2019/

29.08.19

28.08.19

28.08.19

I anticipated a rather 'symphonic' approach and was satisfied in this expectation when the first movement opened in an exalted Allegro maestoso statement of regal proportions. The movement has the nature of a Ballade. The opening was certainly appropriately noble here and majestic for this great masterpiece. Her cantabile was honed to the perfection of song. Avdeeva plays in a truly aristocratic manner with superbly expressive, blue-blooded tone of great self-confidence and pride. Her rubato is affecting and just the sheer number of subtle pianistic 'things' she does at the keyboard is so imaginative - a complete piano technique - all degrees of staccato up to staccatissimo, a wide dynamic range, a caressing legato, the correct durations of notes were all carefully observed. Avdeeva is also tremendously intense emotionally and utterly convincing. Chopin gives us a vision of a turbulent emotions which veer wildly between courageous strength and self-confidence in the face of the sudden reversals and obstacles life offers us and the lyricism of contemplated beauty and resignation.

Fantasiestücke, Op. 12

Paris

Six menuets

25.08.19

Nocturnes Op. 27

For my sensibility, the Nocturne Op. 27 No.1 in C sharp minor is an elegiac nighttime meditation on the nature of existence with a rather tortured, 'realistic' central section. Chopin always examined both sides of life's coin. His music is never monochromatic but highly inflected and colored by a tumult of contrasting emotions.

Świgut was emotionally warmly expressive as she began a definite narration. The two worlds of the real and unreal were brought together in almost shocking conjunction with the eruption of energy she brought to the piece and her excellent technique. Her cantabile and rubato were emotionally affecting. She has a particular affinity with the works of Chopin which clearly comes from deepest love of this composer rather than egocentric projection – there is a substantial difference. A fine performance of this mysterious work so full of inner contradictions.

Eric Lu won First Prize at The Leeds International Piano Competition in 2018 and made his BBC Proms debut with the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra and Long Yu in summer 2019. He is currently a member of the BBC New Generation Artist scheme.

C.M. Girdlestone described the opening Allegro as ‘having the light of a March day when a pale sun shines unconvincingly through fleeting showers.’ All the opening phrases were eloquent and full of subtle gestures of grace, light tone, sensitive touch and good taste. The movement was certainly 'Mozartian' as I conceive it in terms of tone, touch and period style. The piano confines itself here to elaborating orchestral themes. Lu is a restrained stylist, a rather classical player in Mozart, who communicates well with the audience and orchestra in quite an intimate rather than demonstrative or declamatory way.

The performance of Concerto in F major Op. posth was full of infectious delight and period charm. Shelley brought out colourful orchestral and delicate piano details and it emerged as a triumph of the styl brillant. The opening Allegro moderato expressed refined nuances and infectious delight in simply making pleasant euphonic music. The melody trips along blithely and undemandingly in this period context. I did not find the Larghetto particularly moving or genuinely nostalgic in the way that the Larghetto in the Chopin F minor concerto can move one to the depths, despite the attempts of Shelley to give it a wistful character. Finely wrought movement but emotionally limited.

Fryderyk Chopin

CLXXVIII

There is a pleasure in the pathless woods,

There is a rapture on the lonely shore,

There is society, where none intrudes,

By the deep Sea, and music in its roar:

I love not Man the less, but Nature more,

From these our interviews, in which I steal

From all I may be, or have been before,

To mingle with the Universe, and feel

What I can ne're express, yet cannot all conceal!

Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1832) J.M.W.Turner

19.08.19

The premiere of this concerto in 1855 in Weimar with Liszt as soloist and Berlioz conducting must have been a spectacle and an experience in sound!

One should consider the opulent riches in the nineteenth century Romantic concerto repertoire : the piano concertos of the Polish-Prussian composer Xaver Scharwenka for example. His 4th Piano Concerto in F minor is overwhelming in his music unjustly neglected in Poland and elsewhere.

The content of the 'rural opera', is the eternal problem of competition for the hand of a beloved girl, fought between Krakowiaks from Mogiła (today Nowa Huta) and the Highlanders. The dispute is over the miller's daughter, Basia, emotionally connected to Stach. Basia's stepmother, Dorota, also secretly loves Stach, who, jealous, promises the hand of her stepdaughter and rival, Góral Bryndas. Rejected by Basia Bryndas and the Highlanders, he takes revenge on the grave by kidnapping cattle from the village. There is a fight between the Cracovians and Highlanders. The peace-maker is the poor student Bardos, who by means of an electric machine, stages a 'supposed miracle', thus reconciling both feuding parties. Dorota, the main perpetrator of all the commotion, allows Basia and Stach to marry, and the reconciled Cracovians and Highlanders participate in dances and games together.

All Photos Wojciech Grzedzinski

And so another fine edition of Chopin and His Europe (Chopin i jego Europa) concludes with a concert that was rather inspiring and certainly expressing optimistic signs for the future of orchestral music in Warsaw. Many fine concerts ahead!

01.09.19

Sunday

20:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Symphonic Concert

Performers

Program

Symphonic Variations

Probably, there are many works that can be indicated is symbolic final of the interwar period in music. However, perhaps the Symphonic Variations by Witold Lutosławski deserves a special place. The composer created this orchestral firework in 1936 and we can hear references to Szymanowski’s music in it. I was sonically overwhelmed by this performance and am constantly astonished at the vivid musical imagination, the scope of his sound palette, the range of emotional expression and sheer grandeur of this great genius of Polish music. Just look at the deep humanism of this noble and majestic face - it says it all.

Violin Concerto in G minor, Op. 67

There has been an recent renaissance of interest in the music of Mieczyslaw Weinberg and to my mind it is supremely overdue. I felt sure that Alena Baeva would bring her visionary talents to the work and so she did.

The opening Allegro molto burst upon us with ferocious energy. Such passionately tortured music was expressed with deep emotional commitment by Baeva. She was in a state of high agitation throughout which communicated itself to the audience and moved us to the depths. The unexpected innocence of a celeste was desperately moving and eloquent in this movement. The violin part is strenuous and without pause. The sheer physical involvement with the violin as a conduit for passionate musical exegesis was without peer. The Allegretto was deeply melancholic. Baeva produced a profound sense of loss with the violin speaking from centre stage in this lament.

The Adagio brought us one dimension deeper into the cavern of Jewish despair. Baeva gave us a long narration of lament, a song sung in the pain and anguish of a great account yet mysteriously redeeming in its beauty and expressive emotion. Hard to contain one's tears. Then without respite the Allegro risoluto where the emotional atmosphere of the work metamorphosed into the merciless power of an invading military force. The kettle drums and ominous, repetitive rhythms emphasized its armed nature. I felt the unremitting torture of the Jewish nation here (no, I am not Jewish, simply human). Baeva rendered the solo voice of the violin with unbearable sorrow as the work concluded in unrelieved despair. A remarkable performance on many levels, musical, philosophical, religious and spiritual.

Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

The Warsaw Philharmonic under their new conductor Andrey Boreyko absolutely came alive and were galvanized with energy in a way I have never experienced before in this hall. The Allegro con brio was powerful and energetic as it should be in the manner in which we are all familiar. But listen to Furtwangler in Berlin during the Second World War for incandescent anger. I found the Andante somewhat lackluster as the ensemble was not as integrated as it could have been. The Scherzo. Allegro - Trio was energetically driven at the expense of expressiveness but the Finale. Allegro was packed with grand dramatic gestures and ambitious dynamic variation. What can one possibly say as a critic that might be new and of interest about Beethoven's 5th symphony?

The essential point of tonight was the introduction of the new conductor Andrey Boreyko to the audience and the absolute transformation of the soul of the Warsaw Philharmonic. This bodes so well for the future of symphonic and orchestral music in Warsaw...

Andrey Boreyko has been named Artistic Director and Music Director of the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, commencing from the 2019/20 season. He has a long distinguished relationship with the orchestra dating back to 2007.

As Artistic Director of the orchestra, he will conduct not only during their subscription series in Warsaw, but he will also participate in all the main Polish Festivals (for example Chopin and his Europe, the Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music and the Ludwig van Beethoven Easter Festival).

His first subscription concert as Artistic Director will be in October 2019 and that season he will also tour to Japan with the orchestra. Prior to that, he will conduct the orchestra in a number of Summer Festivals as Artistic Director Designate in August and September 2019.

Saturday

17:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Chamber Music Hall

Piano recital

Nikolai Demidenko period piano

Nikolai Demidenko scarcely needs any introduction as he has extensive worldwide recognition and critical acclaim. His passionate, virtuosic performances and musical individuality have marked him as one of the most extraordinary pianists of of our time.

Soirées de Vienne - Valses-Caprices d'apres Fr. Schubert No. 6 S. 427

The pianist and scholar Dr. Leslie Howard writes of these works:

The Soirées de Vienne addressed such a real need and an obvious difficulty that their present neglect is quite shameful. Schubert produced several hundreds of short dance pieces for piano, many of them in sets which were possibly intended for continuous dancing or domestic entertainment but which are, because of their individual brevity, the sameness of their length, and their often unvaried tonality, very awkward to programme in concert. [...] No 6 of the Soirées de Vienne was a great favourite in Liszt’s day and was much recorded earlier in the twentieth century.

The Soirées de Vienne addressed such a real need and an obvious difficulty that their present neglect is quite shameful. Schubert produced several hundreds of short dance pieces for piano, many of them in sets which were possibly intended for continuous dancing or domestic entertainment but which are, because of their individual brevity, the sameness of their length, and their often unvaried tonality, very awkward to programme in concert. [...] No 6 of the Soirées de Vienne was a great favourite in Liszt’s day and was much recorded earlier in the twentieth century.

On the copy of the 1825 Buchholtz piano created by Paul McNulty - Chopin's favoured Warsaw 'pantaleon' or piano - Demidenko created a period feel and atmosphere of some intensity. An imaginative pianist, he extracted a charming tone from the Buchholtz with his refined touch. However from the interpretative point I yearned for more Viennese affectation, charm and gemütlichkeit. These are intangible qualities that come from within and I felt that he was perhaps not quite superficial enough in this enchanting salon work.

Sonata in A major D. 959

I felt Demidenko was far more at home in this profoundly philosophical work. here we have the triumph of expressiveness over technical virtuosity. The ubiquitous theme of the romantic wanderer' perambulating through life in a state of lyricism, rudely awakened by grim, even hostile reality. Dreams and reality, imagination and perception. This sonata is one of the three most profound having within the ever-present shade of Beethoven who had died in 1827. Schubert was to die just a few months short of two years later.

Demidenko gave the opening Allegro a suitably majestic tonal world. HoWever although the cantabile was superb, I was anticipating more tension prefiguring the Andantino. I am always struck how Schubert benefits so greatly from performance on a period instrument, arguably more than an other composer. From the tone and touch he was clearly experienced playing earlier historical instruments. The phrasing again revealed great sensibility and expressiveness using the evocative colour spectrum of the instrument to great effect. He has fine control of touch, tone, dynamics and articulation.

The emotional fulcrum of this great sonata is the Andantino movement in F-sharp minor. We are irritably reminded of songs from Winterreise and the melancholic meditation contained within the cycle. The music of the middle section is of abandoned, mindless and heartless violence that obliterates the surrounding lyricism. Alfred Brendel has made a connection with the tragic painting of Goya, especially The Third of May 1808, where the animalistic violence of the firing squad is ranged against the defenseless 'soft' human targets. Demidenko was deeply poetic and introspective here. The tempo was of an ardent nocturne or love song. The hysterically violent section sounded magnificently variegated and fragmented on the Buchholtz.

The two movements that follow this existential exploration of the soul, soften the tragedy although linked symbiotically to it. Demidenko made the Scherzo rhythmically infectious and persuasive with a lyrically reflective central section. The Rondo. Allegretto contained a graceful song. The rhapsodic phrases were deeply felt with much dynamic variation and refined touch and tone. Turbulent emotions erupted on the Buchholtz with a growling vengeance yet the last statement of theme was remarkably innocent in character. The silences Demidenko calculated here were replete with a sense of destiny waiting ominously in the wings.

A formidably expressive account of this late sonata by Schubert which for me simply emphasized the suitability of period instruments for this composer's characteristically colored sound palette and timbre.

Barcarolle in F sharp major

I felt this to be a remarkably successful and revelatory expressive interpretation of this great work. On the period piano, the temptation to dynamic exaggeration is prevented purely by the design of the instrument itself and its inability to insensitively overwhelm with vast sound capacity. The opening simply set the mood and sound world of the waterscape without a crash into the pier.

Tarantella in A flat major

This was a very spirited performance that had a few solecisms which only proved the quite acceptable human fallibility of this great artist.

Berceuse in D flat major

A persuasive and poetic view of the work marred just a little by the malaise hinted at above.

A stylish and spirited performance of this rarely performed but rhythmically exciting and youthful work of Chopin. I was so happy he chose it, possibly my favourite early Chopin piece. He seemed happy with it too and really enjoyed playing it. The bolero was originally a lively Spanish dance in triple metre originating in the 18th century and popular in the 19th. It bears a resemblance to the polonaise which is perhaps why Chopin wrote one.

|

| A Bolero Dancer is a painting by Antonio Cabral Bejarano |

Impromptu in F sharp major

A fine performance

Polonaise-Fantasy in A flat major

This work in the so-called ‘late style’ of the composer was written during a period of great suffering and unhappiness. He labored incessantly over its composition and what emerged is one of his most complex works in his oeuvre both pianistically and emotionally.

I found Demidenko's interpretation of this late, supremely difficult work individual, poetic and profound. On the Buchholtz, Demidenko reduced the dynamic range which, together with his musically penetrating phrasing, allowed the work to develop into an internal meditation and a haunting search for certainty in our tenuous hold on life. So much emotion was expressed here in a chiaroscuro range of moods and colours, it was overwhelming for me. An absolutely unique and convincing vision of the work.

30.08.19

An informal talk with Kristian Bezuidenhout in the courtyard of the Bach Museum in Leipzig, 19th June 2019, during the Leipzig Bach Festival Bach, Court Compositeur

Friday

20:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Symphonic Concert

Performers

Program

Symphony in D major (‘Haffner’), K. 385

The parallel between this concerto and the opera Cosi fan Tute was highlighted by the Mozart and Haydn authority H.C. Robbins Landon: the stage work in which Mozart most brilliantly and perfectly solved the structural, dramatic and musical problems which had occupied so much of his best operatic efforts' and the concerto 'contains the essence of Mozart's approach to the sonata form: unity within diversity. He deemed this concerto 'the grandest, most difficult and most symphonic of them all,' while noting 'the complete negation of any deliberate virtuoso elements.'

The Mozart authority Cuthbert Girdlestone wrote of the Allegro maestoso opening movement 'Few of Mozart's compositions show themselves to the world with so original a frontispiece and none opens in such bold tones. Its heroic nature is apparent in its first bars—not the sham heroism of an overture for which a few impersonal formulas suffice, but that which expresses greatness of spirit.'

The Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century is celebrating a thirty year anniversary of working with the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute so this is rather a special concert on many levels.

Mozart moved from Salzburg to Vienna in 1781. He began anew his new post in a mood of optimism and independence of spirit. he was now working for himself so had to accustom himself to the social and musical life of Vienna. In the time-honored manner private lessons and concerts as a keyboard soloist kept the wolf from the almost marital door.

|

| Bernado Belotto (aka Canaletto) 1720-1780 Schoenbrunn Palace, Vienna 1759 |

In 1776, Mozart had been commissioned to write a serenade for the wedding of the daughter of a merchant named Sigmund Haffner. This was so highly appreciated, in the summer of 1782 Mozart was asked by his father Leopold to provide a celebratory symphony for the ennoblement of Haffner's son (incidentally Mozart's age) Mozart was overworked and was planning his own wedding disapproved by his father. Mozart sent the new music to Leopold and then promptly forgot it. In spring when he needed a composition for a Viennese concert, Mozart looked over the score over again and wrote to Leopold: "my new Haffner symphony has positively amazed me, for I had forgotten every single note of it. It must surely produce a good effect." A contemporary report noted an 'exceptionally large crowd'. The Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II remained for the entire concert'against his habit' and joined 'such animous [sic] applause as has never been heard of here.'

The orchestra was conducted with great physical animation from a raised stool by the orchestral leader. The opening of the Allegro burst upon us with a rush of sheer joy. Mozart wrote to his father Leopold that the movement 'must be played with great fire.' The movement seems dominated by Haydn with a theme of great succinctness and concentration. The sound texture of the orchestra was captivating in ensemble and the energy and commitment insisted upon by the leader, most infectious.

The Andante has an urbane, gemütlich atmosphere so typically Viennese in its coffee-house conversational tone. The orchestra seemed to instinctively understand the social charm contained within this movement. Attractive orchestral detail and elegant phrasing. The Minuet was remarkably lively and rather humourous but could have been more 'affected' in the Viennese sense. Mozart marks the Finale to be played 'as fast as possible'. It has an operatic quality as does almost everything Mozart wrote. Echoes of Figaro perhaps? At all events Vienna has rejuvenated Mozart after the claustrophobia of Salzburg. The Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century with their period instruments and lead by the leader, a volcano of communicative energy, raised the composer to life like Lazarus. The movement was fiery, energized with irresistible forward momentum. A powerful and satisfying performance of one of Mozart's greatest symphonies.

Kristian Bezuidenhout, playing a Paul McNulty copy of a Graf instrument, then joined the orchestra for the great Mozart concert aria, Ch'io mi scordi, for soprano, piano and orchestra, KV 505. Mozart's manuscript copy is dated December 26, 1786. It is an 'insertion aria' to Idomeneo, Act II, Scene 1, with the libretto by Abate Giambattista Varesco. The piece includes an obbligato part for keyboard, which was played by Bezuidenhout. The aria is marked Rondo, a fashionable form for vocal works at that time. The soprano Rosanne van Sandwijk sang with accurate intonation and affecting expression, alternating with panache the flourishes on the piano. Certainly an opera seria composition and sung in that style.

Interval

After the interval the Mozart Piano Concerto in C Major K. 503. In December 1786 Mozart was planning a visit to Prague for performances of The Marriage of Figaro. He performed this concerto in Vienna on December 5, 1786, amazingly only the day after he completed the score (ink still moist on the page). On the 6th he completed Symphony No. 38 in D major K. 504 which became known as the "Prague" Symphony. The concerto was inexplicably neglected after his death. In 1934 Artur Schnabel performed the work with the Vienna Philharmonic under George Szell it had not been performed in Vienna for 147 years! Only after the Second World War did this great concerto entered the repertoire.

The parallel between this concerto and the opera Cosi fan Tute was highlighted by the Mozart and Haydn authority H.C. Robbins Landon: the stage work in which Mozart most brilliantly and perfectly solved the structural, dramatic and musical problems which had occupied so much of his best operatic efforts' and the concerto 'contains the essence of Mozart's approach to the sonata form: unity within diversity. He deemed this concerto 'the grandest, most difficult and most symphonic of them all,' while noting 'the complete negation of any deliberate virtuoso elements.'

The Mozart authority Cuthbert Girdlestone wrote of the Allegro maestoso opening movement 'Few of Mozart's compositions show themselves to the world with so original a frontispiece and none opens in such bold tones. Its heroic nature is apparent in its first bars—not the sham heroism of an overture for which a few impersonal formulas suffice, but that which expresses greatness of spirit.'

Kristian Bezuidenhout conducted the movement from the keyboard fluently and with penetrating, majestic energy. The variety of colour he extracted from the Graf, his immaculate articulation, pedalling to vary the timbre and the beautiful registral contrasts were outstanding.

The second movement, Andante, was performed with an affecting limpid innocence, simplicity and calm reflectiveness by Bezuidenhout. Fine legato and cantabile lines. The Allegretto finale is so obviously operatic ,surrounded as it were by the composition of some of the most popular and tuneful of the Mozart operas. Here too dance music, the gavotte from the ballet music for Idomeneo. Bezuidenhout expressed all the wit, tendresse as well as a similar aristocratic poise and majesty as engaged from the first movement. There is no posturing just the finest of classical balance with a tasteful expression of heightened sentiment towards the central section of this rondo. Bezuidenhout conducted this movement with a similar elegance and emotion to the music itself, yet not denying its restrained passionate content.

The second movement, Andante, was performed with an affecting limpid innocence, simplicity and calm reflectiveness by Bezuidenhout. Fine legato and cantabile lines. The Allegretto finale is so obviously operatic ,surrounded as it were by the composition of some of the most popular and tuneful of the Mozart operas. Here too dance music, the gavotte from the ballet music for Idomeneo. Bezuidenhout expressed all the wit, tendresse as well as a similar aristocratic poise and majesty as engaged from the first movement. There is no posturing just the finest of classical balance with a tasteful expression of heightened sentiment towards the central section of this rondo. Bezuidenhout conducted this movement with a similar elegance and emotion to the music itself, yet not denying its restrained passionate content.

Finally the wonderfully titled song, Abendempfindung an Laura (Evening Feelings for Laura) KV 523. It was pleasantly sung by the mezzo-soprano Rosanne van Sandwijk, but I felt she could have made more expressive use of the poetry and perhaps slightly finer control of her intonation.

* * * * * *

https://michael-moran.org/2019/06/16/bach-court-composer-bach-festival-leipzig-14-june-23-june-2019/

I was fortunate enough to be able to arrange an informal talk with this Artist in Residence. I neglected to write it up at the time so I will try to make amends here from my notes. He and Isabelle Faust the previous evening had given a superfine virtuoso performance of six Bach sonatas for violin and harpsichord. We sat in the attractive courtyard of the Bach Museum.

I spoke a little about my own background with the harpsichord in London in the 1970s, studying with Maria Boxall (editor of the keyboard works of John Blow and author of a harpsichord method). I witnessed the extremely exciting early days of the so-called 'Early Music' revival in London. This was when Christopher Hogwood was just becoming known, a youthful Trevor Pinnock was playing in Hampstead parish churches, Ton Koopman was giving solo recitals as was Bob van Asperen, Gustav Leonhardt and Nikolaus Harnoncourt were revolutionizing the performance practice and study of Bach and performing at St. John's Smith Square and the Spitalfields Festival. We spoke of his background in South Africa and Australia - with some animation me being Australian and also knowing South Africa well after researching a recent biography I wrote!

Kristian began with a surprising remark in view of his career, that his first experience with the harpsichord and fortepiano was an 'alien encounter'. He had studied the modern instrument. However he was overwhelmed on first hearing Gustav Leonhardt playing the works of Antoine Forqueray and Jacques Duphly.

As the 2019 Leipzig Bach Festival was entitled Bach, Court Compositeur, we talked at length about the significant influence of French music and performance tradition on Bach. He considers that one must fully understand the cantatas and sacred works (his first love) to be able to meaningfully play the keyboard works. He pointed out the familiarity of the liturgical year to music lovers as art of the congregation in Bach's day. The conclusion of the St. Matthew Passion is of course deeply tragic but the congregation knew that the following week the Resurrection was coming.

We then talked about his remarkably close artistic relationship with the magnificent Freiburger Barockorchester (Artistic Director), his role as Principal Guest Conductor of the English Concert, his conducting association with the outstanding Les Arts Florissants and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. He was awarded the Grammophone Artist of the Year in 2013. At this point he expressed his great enthusiasm for Paul McNulty's reproduction period pianos. He has recorded the complete Mozart piano concertos on a McNulty copy of an Anton Walter & Sohn instrument, Vienna 1805 with the Freiburger Barockorchester under Gottfried von der Goltz. One of my favorite recordings of his is the breathtakingly brilliant youthful and prodigious Mendelssohn-Bartholdy Double concerto for Violin and Piano (with Isabelle Faust) and the Piano concerto in A minor.

We then began to discuss in some detail the keyboard implications of the fascinating fingering of Francois Couperin and how each finger and key had been given its own character during the French classical tradition. I also mentioned that this was an influence on the penciled in fingerings of Fyderyk Chopin as well. Unfortunately at this point it began to rain and we had to leave the delightful open courtyard and draw the informal talk to a close, promising to meet in Warsaw at the concert I have reviewed above...

29.08.19

Thursday

20:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Chamber Music Hall

Chamber concert

Performers

Grand Duo polonais op. 8 /Op.5

The Wienawski brothers respected the Polish composer Stanislaw Moniuszko and he them. In this work they celebrated two of his famous songs - Kosak and Maciek. The work requires a significant virtuoso display on the part of the violinist especially the Aleksey Verstovsky's Polonaise that concludes the piece. The work is well near forgotten today, but for me possesses a marvelous folkloric character of affecting simplicity and tunefulness. Kholodenko and Baeva gave a spirited account of the rare piece.

Violin sonata No. 2 in D minor Op. 121

The almost unrelenting Romantic passion of the D minor Violin Sonata Op 121 makes it a remarkable work. Schumann dedicated it to Ferdinand David, the violinist to whom Mendelssohn dedicated his violin concerto. The piece was premiered by Joseph Joachim and Clara Schumann at a concert on 29 October 1853. This was the beginning of a famous musical partnership that lasted for many years. Towards the end of the year Joachim wrote enthusiastically to his friend Arnold Wehner, Director of music at Göttingen:

You know how expressively Clara interprets his [Schumann’s] music. I have extraordinary joy in playing Robert’s works with her, and I only wish you could share this joy … I must not fail to tell you about the new Sonata in D minor which Breitkopf & Härtel will bring out very soon. We played it from the proof-sheets. I consider it one of the finest compositions of our times in respect of its marvellous unity of feeling and its thematic significance. It overflows with noble passion, almost harsh and bitter in expression, and the last movement reminds one of the sea with its glorious waves of sound.

Kholodenko and Baeva have such a symbiotic musical relationship the slow introduction Ziemlich langsam - Lebhaft was truly majestic before the heated passionate agitation of the development and coda. The second movement scherzo (Sehr lebhaft) had tremendous forward momentum and drive to reach a climax with the chorale melody ‘Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ’, played fortissimo by both these brilliant players. They connected beautifully to the tender serenade variation of the movement that follows (Leise, einfach). The final Bewegt movement was emotionally as turbulent as one could possibly wish, fitting perfectly the idea of 'waves of sound' Joachim describes above. There was moving lyricism here too until the magnificent coda that concludes the work.

Kholodenko and Baeva have such a symbiotic musical relationship the slow introduction Ziemlich langsam - Lebhaft was truly majestic before the heated passionate agitation of the development and coda. The second movement scherzo (Sehr lebhaft) had tremendous forward momentum and drive to reach a climax with the chorale melody ‘Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ’, played fortissimo by both these brilliant players. They connected beautifully to the tender serenade variation of the movement that follows (Leise, einfach). The final Bewegt movement was emotionally as turbulent as one could possibly wish, fitting perfectly the idea of 'waves of sound' Joachim describes above. There was moving lyricism here too until the magnificent coda that concludes the work.

Drei Romanzen Op.22

Richard Strauss and his wife the soprano Pauline de Ahna

Clara and Robert Schumann moved to Düsseldorf in 1853 into a large house. Clara composed the Three Romances for violin and piano, Op. 22 in the summer. She dedicated her Three Romances to the violinist Joseph Joachim (1831-1907). He even performed them for King George V of Hanover.

I was greatly moved by the lyricism of these pieces, particularly the G minor which has such a poignant theme that soars like a swallow, melancholically gliding above the following outgoing mood of the middle section. The intimate musical 'conversation' between these two brilliant musicians was affecting in a profoundly humanist way. The other Romances conform to a similar lyrical pattern - lyricism enclosing agitation, the Romantic temperament in miniature. The yearning violin of Baeva touched the heart supported by the complex piano underpinning of Kholodenko.

( Time Life Pictures/Mansell/Getty Images )

Sonata in E flat major for violin and piano, Op. 18

This Sonata for violin and piano in E flat major, Op. 18, of 1887 is the last chamber piece to come from Richard Strauss. He wrote it at much the same time as the renowned symphonic fantasy Aus Italien and the tone poem Don Juan. The melodies are sensually seductive and rather deeply engaged in the inner emotional world.

The piano opens the Allegro ma non troppo first movement with a some nobility which quickly gives way to a beautiful, flowing melody on the violin which Baeva made much of expressively. A passionate musical dialogue theme between the two musical partners in a theme marked espressivo e appassionato, serves as the proper second theme. The second movement is called Improvisation and marked Andante cantabile. I wondered at the terminology as this song is so beautifully and carefully imagined and composed. The Finale begins with a lugubrious Andante on the piano. Allegro is the tempo of the actual movement and I think this was the only part of the sonata where I felt that Kholodenko was tempted into dynamically overwhelming the Baeva violin as the symphonic character of the writing inexorably drew in the players. The sonata closes on truly joint triumphal note. Overall an uplifting performance with a few questions of dynamic balance which did not detract hardly at all from the total emotional engagement.

Wednesday

22:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Chamber concert

Performers

Corina Belcea (violin)

Axel Schacher (violin)

Krzysztof Chorzelski (viola)

Antoine Lederlin (cello)

String Quartet in B flat major, Op. 18 No. 6

Beethoven reordered all six works in the Op.18 set after finishing them in 1800. The six quartets were dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz and were first published in Vienna in 1801.

The first movement theme is marked Allegro con brio and is tremendously jolly and merry. The Belcea presented it energetically, urgently and with such intensity one was overawed. The second theme bubbled over almost into the manic. The Adagio became a deeply reflective internal innocent song of the heart. Such a simple and affecting melody. The Belcea brought a winning blithe character to this movement and produced a superbly subtle conclusion. The Scherzo with them was packed to the brim with energy, humour, playfulness and commitment. This ensemble has a seemingly impregnable cohesive strength The phrasing and dynamic variation were brilliantly expressive. The final La melinconia Adagio - Allegretto quasi Allegro expresses deep sadness from the outset with long, legato yearning phrases. Sudden clouds of gloom descend during this movement, the moods striking like lightning with the Belcea. We then appear to take a optimistic walk in dance rhythm in the bucolic countryside to lift the despondent mood. A brief return to gloomy thoughts or is it simply prosaic reality. The Belcea depict these fluctuating, flickering emotions so expressively until the final triumphant, joyful up tempo conclusion to this landscape of refraction.

String Quartet in F minor (‘Serioso’), Op. 95

In their next work, the String Quartet in F minor Op. 95 entitled 'Quartetto serioso' by Beethoven for rather mysterious reasons, was composed in 1810 at the same time as the Egmont Overture. The tense, terse compactness of the short opening Allegro con brio suited the passionate penetration of the Belcea Quartet to perfection. The interaction of voices was quite wonderful with extraordinarily committed playing especially by the cellist Antoine Lederlin. He also shone in the detaché playing in the extraordinary Allegretto with its inspired and musically sophisticated mixture of cantabile and fugato polyphonic elements. There is such a sense of existential abandonment in this movement. The heartbeat rhythm is slowing in the struggle of the spirit to rise above earthly care.

The abrupt, violent transition to the Allegro assai vivace ma serioso to anger and resentment was almost frighteningly accomplished in its urgency. The agitation settles. Musically so much makes absolute sense with this brilliant quartet who play with such full-blooded conviction and authority. The powerful modulations were brilliantly accomplished by the quartet in the marvelous Trio.

The fierce, irrepressible energy of Beethoven which always eschews languishing in depression, suited the virtuosic command of these players so well as we moved on from the elegiac introduction of the Larghetto espressivo through all manner of harmonic landscapes, mercurial moods and fantastic contrasts - a theme desperate for resolution as we move accelerando into the passionate even ecstatic flourish and elated F major coda. A deeply satisfying performance of this extraordinary and galvanizing quartet.

The fierce, irrepressible energy of Beethoven which always eschews languishing in depression, suited the virtuosic command of these players so well as we moved on from the elegiac introduction of the Larghetto espressivo through all manner of harmonic landscapes, mercurial moods and fantastic contrasts - a theme desperate for resolution as we move accelerando into the passionate even ecstatic flourish and elated F major coda. A deeply satisfying performance of this extraordinary and galvanizing quartet.

String Quartet in C sharp minor, Op. 131

William Blake, Elohim Creating Adam 1795–c.1805

After the interval the String Quartet in C sharp minor Op. 131.

There are five interlinked movements:

I.

|

Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo

| ||

II.

|

Allegro molto vivace

| ||

III.

|

Allegro moderato

| ||

IV.

|

Andante, ma non troppo e molto cantabile

| ||

V.

|

Presto

| ||

VI.

|

Adagio quasi un poco andante

| ||

VII.

|

Allegro

|

What can I possibly say of any true or lasting significance about this immortal work wherein Wagner described the unearthly opening fugue as 'the most melancholy sentiment ever expressed in music'. Even this remark does not do justice to the beginning which can really only be termed 'the dark night of the soul' on the face of the deep before the creation of man. Listen to it yourself is the finest advice I can offer, feel how it affects your soul and come to your own personal conclusions. Ludwig van Beethoven, this profoundly isolated human in ways few of us can contemplate, let alone survive, transformed himself through sheer spiritual courage, juggling the shifting kaleidoscope of his obsession with variation form, the desperate memory of past joys. There are such savage pizzicatos in the Presto. Profound melancholy is laid into the Adagio and savagery into the rhythm of the final Allegro, with its fluctuation of moods like weather in a winter alpine landscape. The Belcea brought irresistible momentum here, an avalanche of passion. Emotions appear to be under control but then escape their binding chains in the Coda which erupts like whipped mercury. In this quartet clouds cross the face of the sun, there are games with rhythm and charm, the dance and the final assertive conclusion in the silence of the mind and senses.

'....though you cried as pure as the bird

when the surging season uplifts him, almost forgetting

he's a fretful creature and not just a single heart

it's tossing to brightness, to intimate azure.'

The Seventh Duino Elegy, Rainer Maria Rilke (trans. J.B. Leishman)

The Belcea Quartet were as profound and spiritually penetrating in this masterpiece as one could ever wish, triumphant in the grueling journey from the ominous oceanic cave into the sunlit sea of acceptance.

Wednesday

19:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Symphonic Concert

At this concert, the Artistic and Managing Director of the Festival, Stanisław Leszczyńki, was presented with the highest artistic honour awarded in Poland known as the Gloria Artis (Gold) for distinguished contributions to Polish culture over many years

|

| Stanisław Leszczyńki Artistic and Managing Director of the Festival Gloria Artis |

Concert Performers

Violin concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 22 (1862)

The Concerto in D minor was composed in 1862 and was premiered in Moscow on November 27 with Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) himself as soloist and Anton Rubinstein conducting. A child prodigy, he was one of the most brilliant and beloved 'virtuoso-composers' of his day, a formidable example of what Yehudi Menuhin described (in his foreword to a biography of Eugène Ysaÿe) as 'that romantic race of mighty men who were violin virtuosi.'

In some ways this performance was an experiment as the work had not been performed before with a period instrument orchestra. The open clamour of a modern symphony orchestra was absent replaced by a fuller timbre. The opening Allegro has a rich melody. I felt this a particularly suitable orchestral ensemble for a different, more moderate view of this piece with its mahogany depth of sound. Some disagreed with me.

Baeva was excruciatingly ardent in the opening theme, romantic yearning transformed into joy. She maintained an intimate connection with orchestra and conductor. The conductor is actually the leader of the orchestra who sits on a raised piano stool slightly elevated above the orchestra before the desk of first violins. The tutti passages were freighted with full period sound, long legato cantabile lines were finely maintained. With Baeva one could not avoid remarking what a superb melodic gift Henryk Wieniawski had been given by the powers on high.

The second movement Romance. (Andante ma non troppo) emerges seamlessly from the first movement as a beautiful outgrowth or bloom. The lyrical theme became airborne like the ravishing song of a lark. At the time, this theme was often performed alone as a solo piece. The Baeva violin sang this enchanting, simple melody which was at once moving yet charming. Baeva turned the final Allegro con fuoco into a marvellously passionate dance à la Zingara (in the gypsy style) full of energy, arrogance and invincibility. Here we had virtuosic abandon and complete commitment to the swirling emotions and driving sprung rhythms of the movement.

Clarinet concerto in A major, KV 622 (1791)

The Concerto in A Major for Clarinet and Orchestra, K. 622 by Mozart is recognized as a timeless masterpiece without peer. Perhaps because it was the last concerto he wrote two months before he died at 35, we have invested it with a deeper significance. Mozart composed the concerto for his friend and fellow Freemason, the clarinetist Anton Stadler (1753-1812). It is reported that Stadler had a special A clarinet that extended below the traditional range. Eric Hoeprich performed on one of these instruments.

Some modern reproductions have been made from this drawing, possibly one being played by Eric Hoeprich this evening, him being one of the world's leading exponents of the historical clarinet. There was no conductor, the soloist leading the orchestra (he was also a founder member and principal clarinet of this orchestra).

This was one of those ‘perfect’ stylistic performances of the work and I am left with nothing to say other than praise. There is such a rich warmth to this remarkable instrument, a true soul to it, a mellow woodiness of rich timbre, colours and texture particularly in the lowest register (down to C) for which the instrument was especially constructed to encompass. Elegant phrasing, refinement and delicacy and in the Adagio of this concerto, that heartbreaking melody, sublime in every way. In the Rondo the original instrument enables a much softer legato line again with such a rich timbre and all the colours of the rainbow. I do not wish to sound trite but one inescapably feels for Mozart this was an addio to life itself.

Variations in B flat major on a theme from Mozart’s 'Don Giovanni' (‘Là ci darem la mano’) (1827/28)

The Variations in B flat major on ‘Là ci darem la mano’, Op. 2 are Chopin’s characteristic reaction to Mozart's Don Giovanni. Thanks to these Variations, Chopin’s fame spread across central Europe. They first moved Robert Schumann, whose youthful review – the first that he wrote – in a Leipzig music periodical, entitled ‘Opus Zwei’ [Opus 2], has acquired a lasting place in music history. That review was written in a fictional style (a device that Schumann would frequently employ):

‘Eusebius came in quietly the other day. You know the ironic smile on his pale face with which he seeks to create suspense. I was sitting at the piano with Florestan. Florestan is, as you know, one of those rare musical minds which anticipate, as it were, that which is new and extraordinary. Today, however, he was surprised. With the words, “Hats off, gentlemen – a genius!” Eusebius laid a piece of music on the piano rack. […] Chopin – I have never heard the name – who can he be? […] every measure betrays his genius!’

Chopin composed the ‘Là ci darem’ Variations in 1827. As a student of the Main School of Music, he had received from Elsner another compositional task: he had to write variations for piano with orchestral accompaniment. As his theme, he chose the famous duet between Zerlina and Don Giovanni from the first act of Mozart’s opera – the one in which overwhelming power and faultless seduction meet maidenly naivety and barely controlled fascination. (Tomaszewski)

Chopin’s ‘Là ci darem’ Variations are Classical in form with an introduction, theme, five variations and finale. They are a marvellous example of the style brillant. Kholodenko conducted this work from the keyboard of a period piano, an 1849 Erard from the National Fryderyk Chopin Institute collection. He opened with the correct indicated deliberate tempo Largo - rather slow compared to the way many pianists begin. He then adopted an effortless styl brillant that was light, elegant and inspiringly stylish. The approach was genuinely expressive of the opera and the lurking demonic nature of it that appears so civilized on the surface. The songlines were a refined cantabile with just the right rhythm. Every repeated phrase was differentiated from the preceding example, not mindlessly repeated as is so often done.

Clara Wieck loved this work and performed it often making it popular in Germany. Her notorious father, who had forbidden her marriage to Robert Schumann, wrote of perceptively and rather ironically to my mind of this work: ‘In his Variations, Chopin brought out all the wildness and impertinence of the Don’s life and deeds, filled with danger and amorous adventures. And he did so in the most bold and brilliant way’. Kholodenko understood this to perfection and his virtuosity was in the ascendant in the transparently impressive articulated left hand passages. The dynamic never became a burdensome thump.

He seemed to be greatly enjoying himself with delicious moments of rhetorical delicacy. Each variation was carefully delineated in character and had the feeling of improvisation or 'on-the-spot' invention. His affectation of gesture was affectingly pure 18th century in its style and artfulness. Kholodenko never at any time approached this work as a virtuoso display piece, which most pianists do. Waterfalls of glittering notes cascaded around us as in the original descriptions of jeu perlé. This was without doubt some of the finest period piano playing I had ever heard.

27.08.19

Tuesday

20:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Piano recital

Performer

Cyprien Katsaris piano

Cyprien Katsaris began to play piano at the age of four, in Cameroon, where he spent his childhood. His first teacher was Marie-Gabrielle Louwerse. A graduate of the Paris Conservatoire, where he studied piano with Aline van Barentzen and Monique de la Bruchollerie, as well as chamber music with René Leroy and Jean Hubeau, he was the only Western European prize-winner in the 1972 Queen Elisabeth of Belgium International Competition.

His international career includes performances with the world’s greatest orchestras, most notably the Berlin Philharmonic, Staatskapelle Dresden, Vienna Chamber Orchestra, Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, NHK Symphony Orchestra (Tokyo), Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, Bucharest George Enescu Philharmonic Orchestra and Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. He has collaborated with such conductors as Leonard Bernstein, Mstislav Rostropovich, Simon Rattle, Christoph von Dohnányi, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Kent Nagano, Sandor Végh, Vladimir Fedoseyev, Leif Segerstam, Dmitri Kitajenko and Karl Münchinger.

He is a most entertaining personality and performer who engages the audience on a personal and humorous level as he shares his passion for music.

The fascinating programme he presented here is most unusual and unlikely ever to be repeated. Chopin had many pupils and influenced many composers. This is a collection of miniature compositions by outstanding stars in the constellation of pupils and composers surrounding Chopin. In an invaluable manner these small pieces create the social atmosphere that Chopin must have experienced.

Program

Mazurka in E minor, Op. 21 No. 2

Lolita – valse brillante, Op. 11

Fontana was not a pupil of Chopin but an utterly selfless friend, amanuensis and composer. His devotion to Chopin and tolerance of his whimsical nature are legendary. The mazurka is a pleasant occasional piece that suited the Katsaris temperament well. The amusingly titled 'Lolita' valse brillante (pace Vladimir Nabokov) creates the atmosphere and social ambiance Chopin must have known.

Mazurka in B flat major, Op. 3 No. 3

Mazurka in F sharp minor, Op. 3 No. 4

Nocturne in E major, Op. 11

Nocturne in G flat major, Op. 39

Tellefsen was a renowned Norwegian piano virtuoso born in Trondheim. After much effort he was accepted as a pupil of Chopin with lessons three times a week, two of them free. This was significant given the high fees Chopin charged his aristocratic pupils. He assisted in the publication of Chopin's works after his death and adopted many of his pupils. His piano works are rather simple and naive and evoke a Chopinesque atmosphere. Katsaris brought out the touch of the oriental, odd harmonies and uncommon sensibility in his the mazurkas. The Nocturne in E major was rather like being offered a box of chocolate eclairs but the G-flat major was quite developed. One could not hep reflecting on the gulf that separates talent and genius.

Le Tourbillon. Galop Brillant, Op. 37

Nocturne in A flat major, Op. 8 No. 1

Polonaise brillante, Op. 21

This pupil lived in Paris from the mid 1880s and took lessons from Chopin for five years. Although a robust physical player he was allegedly Chopin's favourite pupil. I found the Galop enormous fun played by Katsaris. The Nocturne in A-flat major was pleasant enough with some rather lovely modulations. The Polonaise was considered to be an excellent attempt by a German student at writing a Chopinesque polonaise in the style brillante. Katsaris understood the wit involved here.

Mazurka in G major, Op. 10

Airs nationaux roumains (excerpt)

Mikuli has had a formidable influence on the evolution of a Chopin tradition. He also studied in Paris with Chopin in company with Tellefsen. He was a successful concert artist in Europe from 1847-1858 and was a major force behind the musical life of Lwów. In 1880 a seventeen volume edition of Chopin was published under his editorship with commentaries and variants. He was a great traveller through Armenia, Bukovina and Moldova and collected the folk music of these regions which he transformed into the Airs nationaux roumains (excerpt). As might be expected Katsaris brought an idiomatic rhythmic understanding to these fascinating folkloric pieces. The Mazurka in G major Op.10 is an attractive work with many charming details.

Mazurka in E flat minor

Barcarolle in G flat major

Das Lebewohl von Venedig (Adieu!) in C minor

'Mon Dieu, quel enfant!' Never has anyone understood me like this child, the most extraordinary I have ever encountered. It's not imitation, it's an identical feeling, instinct, which makes him play without thinking, with all simplicity as if it could not be any other way. Fryderyk Chopin quoted in the Viennese journal Der Humorist, 22 February 1843.

He did penetrate the mysteries of this style almost perfectly in imitation. How might he have developed had his life been longer. The E-flat minor mazurka has definite echoes of Chopin, in fact almost a modern jazz feel about it with Katsaris. The Barcarolle was not one as I imagine it but it was flowing and had a rather advanced figuration. This glorious flower was cut down in Venice at the age of 14, where he had actually travelled for a cure. It was here he wrote the desperately moving Das Lebewohl von Venedig (Adieu!) in C minor which appeared after his death. The harmonic progressions were advanced to say the least. A deeply tragic yet interesting piece.

Waltz in E flat major

‘Spring’ Polka in F major

Trifle in B flat major

Polonaise in E flat major

Nocturne in A flat major

Villanella in D flat major

Znasz-li ten kraj [Connais-tu le pays?] (tr. Henryk Melcer-Szczawiński)

Gwiazdka [L’étoile] (tr. Bernhard Wolff)

Mazurka in E flat major from the opera Halka

The Waltz was pleasant enough and charming as was the 'Spring' Polka which depicts the society of the day. The 'Trifle' certainly was one but fetching I suppose as are many trifles. As this recital progressed I could think of no better pianist than Cyprien Katsaris for these pieces which need 'lifting' to their true status in salon charm. The Polonaise and Nocturne appeared rather inconsequential but the Villanella in D flat major painted a picture of how civilized and full of graces the society must have been at a certain level. The Connais-tu le pays? is also a charming piece which evoked a period more civilized than ours. Gwiazdka unfortunately has rather a chocolate box character. The Mazurka in E-flat major from the opera Halka has an immense 'call to the floor' introduction which is such fun with its lively rhythms!

Dumka St. Moniuszki. Parafraza [Dumka by Stanisław Moniuszko: paraphrase]

A pleasant enough paraphrase with its interweaving of voices and lyrical atmosphere

A pleasant enough paraphrase with its interweaving of voices and lyrical atmosphere

Die Spinnerin, Op. 5 No. 10 (based on Moniuszko’s song ‘Prząśniczka’ [The spinstress])

This piece is fundamentally a recasting of the music of the song. It is a particularly, tuneful piece.

This piece is fundamentally a recasting of the music of the song. It is a particularly, tuneful piece.

Le Cosaque, Op. 123 (based on Moniuszko’s song ‘Kozak’ [The Cossack])

This is an effective, rhapsodic, dramatic piece which ties up many of the loose ends. I found the work highly enjoyable.

Fantasy on a theme from the opera Halka, Op. 51

A friend of Chopin's from studies with Elsner. A respected pianist and piano teacher. This is a tremendous virtuoso display piece which builds a picture of the contemporary society. Even if impressive rather dull in overall impact. Such pieces were popular at the time.

Katsaris, as an apology for an encore, then made announcement to the effect that in the absence of 'memorable tunes' in modern day classical music, he would improvise on a medley of film music, mainly that of the French composer Michel Legrand. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg brought back so many memories of my misspent youth. As a last effort he played a 'World premiere' transcription of a Chopin song which I found interesting. There were some amusing moments when he called for 'Veronica the Page Turner' but Igor in Bermuda shorts, plimsolls and a printed T-shirt wandered over to turn the pages.

27.08.19

Tuesday

17:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Chamber concert

Performers

Program

String Quartet in D major, Op. 18 No. 3

‘Razumovsky’ String Quartet in E minor, Op. 59 No. 2

String Quartet in F major, Op. 135

Having heard the Belcea Quartet before in this festival, I consider them to be a wonderfully inspired group of mixed nationalities (the violinist Corina Belcea after which the quartet is named, is an impassioned Romanian artist). Most recently they performed in Warsaw in August 2016, 2017 and 2018. As a result I was keenly anticipating this concert.

Many composers such as Schubert worked in the intimidating shadow of Beethoven. In facing the composition of quartets he faced the shadows of Haydn. In the set of Opus 18 quartets Beethoven mastered the style of his predecessors and explored new domains of musical expression. The independence of the four parts is so much greater than in the works of previous quartet composers. This refined, subtle and gentle quartet (1798-1800) was the first he composed and was dedicated to Prinz Joseph von Lobkowitz (1772-1816). The six quartets of Op. 18 constitute Beethoven's most ambitious project of his early Vienna years. What promise of genius lies within...

The opening Allegro mainly on solo violin is a gentle cantabile song of a most lyrical and yearning theme, rather in the style of Mozart. The movement flows with the ease of a country brook through a field in summer. It then becomes bright, delightful and 'conversational' in tone with many different themes. The fact that the Belcea members sit noticeably close together assists in maintaining an intimacy of musical inspiration. The Andante con moto second movement proceeded in the manner of elegant drawing room conversations of restrained emotion and gemütlichkeit, expressive and genial. It is pervaded by a warm and rather ardent atmosphere, much in the genre of the Lied. They made the delightful detaché section rather witty. Their playing is supremely artful with a most tender affecting conclusion. The third movement is marked Allegro but is in fact a Scherzo and has quite a lively folk dance character as well as replete with elegant gestures which suited the Belcea admirably. The Presto is quite a rumbustious romp from beginning to end. It is rather good-humoured in the manner of Haydn. In this movement the quartet played with tremendous commitment and enthusiasm and concluded in such a humorous manner!

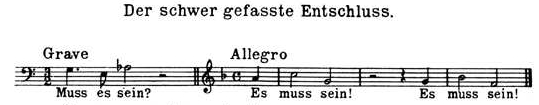

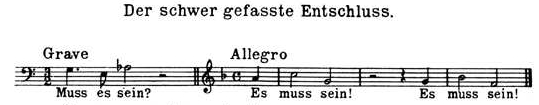

The String Quartet in F major, Op. 135 (1826) is Beethoven's last complete composition. Was it intended to be or was it the beginning of another set ? And the key to the true character of this enigmatic work might lie in the interpretation of its last movement, over which Beethoven famously wrote two short musical motifs and a title:

(The resolution reached with difficulty: Must it be? It must be! It must be!)

Are we to take this question and attempt an answer existentially or believe Anton Schindler, Beethoven's secretary, who tells us it was written in response to the prosaic housekeeper's demand for more money or perhaps a request for increased funds from his publisher. This enigma can never be fully solved so listening to the music itself is the finest thing we can do.

In the Allegretto opening movement the music proceeds delicately and blithely with strong part-writing in fine detail and subtlety of harmony. The Belcea extracted wonderful tonal colours in this movement. However, there are shadows and the grey clouds are massing on the horizon. The Vivace has a light scherzo-like character with many colours that emerge in a chiaroscuro landscape of suppressed energy. The Trio is a unbridled affair of uncontrolled abandon. The emotional commitment the Belcea brought to this movement and the quartet as a whole was immense.

The mood of the Lento assai - cantante e tranquillo gives one the impression of a man looking back over the events of his past life in resigned emotion. He feels a rapidly retreating and fading future life ahead. Beethoven was to die the following year. The feeling of listening to the expression of his intuition is unbearable in this deeply introspective movement. The harmonic developments are 'abstract' but manage to move the soul to the deepest recesses. The Belcea maintained their perfectly accurate and intense intonation, uncannily as if they were one organism performing the music. This music is to me a profound reflection on the emotional self-consciousness of age.

The Grave, ma non troppo tratto has always seemed to me an angry rebuttal of mortal destiny. This contains the so-called Difficult Resolution illustrated above. The moods shift like autumn storms and the intensity of the Belcea affected me in an inexplicable way. Shafts of despair of screaming string timbre strike the heart in its innermost chambers. Then expressions of desperate almost hysterical joy as existence continues. False conclusions and then pizzicato passages which for me held an element of grim if delicate humour. Optimism graces the conclusion to this remarkable quartet - 'Must be!'

After the interval the ‘Razumovsky’ String Quartet in E minor, Op. 59 No. 2. This set shows a formidable development in style over the Op.18 set even after the relatively short period of 8 years. The Russian Ambassador to Vienna, Count Andreas Kirillovich Razumovsky (1752-1836) commissioned them. Razumovsky was a principal patron of Beethoven until his wealth was almost wiped out by a disastrous fire in 1814. He maintained a permanent string quartet from 1808 to 1816 led by Ignaz Schuppanzigh (1776-1830) who played in many premières of Beethoven's works including quartets. Razumovsky himself, an accomplished musician, occasionally played second violin.

These quartets made unique musical demands on the listener never before experienced. The opening Allegro is characterized by shifting mercurial moods and a feeling that made me recall a pantheistic line of the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas : The force that through the green fuse drives the flower, drives my green age. Again the uncanny impression of the Belcea playing as a single organism, playing passionately as one. There is a dark focus to this quartet that struggles into the light accompanied by a definite feeling of a heartbeat on the cello. The beautiful opening to the Andante con moto plays on the strings of the heart. The violin soars like a lark above the rest of the ensemble. Again we feel the rhythm of the regular heartbeat over the panting of nervous despair. Marvellous reflective and meditative polyphony is embedded in this movement. Passionate outbursts are quickly controlled while this heartbeat ensures life and drives the while movement along to its conclusion. I felt it was like crossing a great ocean or walking a long distance.

With the third movement Allegro (Scherzo) there is a complete transformation of mood to sunny optimism contained within the theme, bound into an infectious dance rhythm. The quartet luxuriated in this harmonic dance. This is followed by a fugal treatment of the theme. Sadness descends over the dance, a broken heart but still dancing. Great bucolic energy invests the final Presto. This is such a dynamically expressive movement, particularly as ignited by this extraordinary Belcea organism. The theme is particularly suitable for passionate development. There is such persistence here after many harmonic detours until the final wild dash for the finish.

The audience erupted in pandemonium at the conclusion of the concert and standing ovations.

The encore was a sublime interpretation of the Cavatina from the Beethoven String Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130.

A concert that restores faith in humanity - what more can one ask of artists?

26.08.19

Monday

20:00

Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall

Piano recital

Yulianna Avdeeva piano

There could not have been a greater and more instructive contrast between pianists, instruments and interpretation only one hour after the end of the recital detailed below. One fruitful historical aspect of the modern world's view of the past has recently developed with pianists like Dimitri Ablogin who perform on historical instruments with completely different keyboard technique. Alongside these developments there is the familiar modern world interpreting the music of the past purely on its own terms with modern 'improved' instruments played by great pianists like Yuliana Avdeeva. No choice or competition is involved here. Both the historical and modern approaches complement each other and add yet another dimension to our exploration of the past.

We are far from the source of Chopin now. Just for a moment consider how different the world would be without electricity. Just think. This was the world Chopin lived in. The point now surely is consistency and integrity of the vision on the part of the artist. Both approaches, under the fingers of fine artists, are extremely valuable contributions to a rounded view of this ironically popular, yet most inaccessible of composers, Fryderyk Chopin.

We are far from the source of Chopin now. Just for a moment consider how different the world would be without electricity. Just think. This was the world Chopin lived in. The point now surely is consistency and integrity of the vision on the part of the artist. Both approaches, under the fingers of fine artists, are extremely valuable contributions to a rounded view of this ironically popular, yet most inaccessible of composers, Fryderyk Chopin.

In Poland a mention of Yuliana Avdeeva is bound to generate intense and passionate discussion. As those of you who are familiar with my account of her winning the 16th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw in 2010, you will know of my strong conviction from the outset that she would win. My opinion of her brilliance is not shared by all in Poland - I simply cannot understand this but then again I am not a Polish melomane.

In the storm of protest that followed this decision I could not agree more with Kevin Kenner, Second Prize winner at the Warsaw Competition in 1990 and a jury member in 2010 - a pianist moreover in whose musical judgement concerning Chopin I have the utmost respect for. In an interview for news.pl he justified the decision in the following words:

“Avdeeva has a very deep understanding of the score, the kind of relationship to the score which no other pianist in this competition had. She looked into the score for her creative ideas. It was the source of virtually everything she did and she was also one of the most consistent competitors throughout the event,” he said.

She has developed tremendously since her competition victory. Her fine tone and refined touch seduced the ear from the moment she touched the Steinway. Avdeeva brings an intellectual seriousness to her Chopin with her unremitting search for artistic and musical truth within the notated score. She brings a self-consistent, fully integrated vision of the composer to us, which, irrespective of one's personal view of her Chopin interpretations, Chopin himself or the instruments at his disposal, creates an 'authentic' and deeply rewarding coherent conception of his music. My word there are many Chopins. We each have our own and those of us who love his music will defend our personal opinion to the death with a passion perhaps not given to any other composer.

To be honest I could not wait to hear the development of one of the most mature, stylish and musically perceptive pianist of the competition, she who presents Chopin as a grand maitre of the keyboard. After all Chopin himself, that Ariel of the keyboard, liked above most of his pupils, the 'masculine' playing of his music by the heavyweight German pianist and composer Adolf Gutmann (1819-1882), much to everyone's confusion at the time.

Avdeeva approached the Op.59 Mazurkas with a noble melodic line rather than in any sense indicating they arose from a more rustic Mazovian conception. In No.1 I found this nostalgic mazurka possessed an eloquent cantabile line but was slightly sentimental and over-pedalled. She presented No. 2 and No.3 as grand works with a noble, rather grand tone. All well and good but for me this was somewhat misplaced and rather inflated their proportions beyond the simplicity and intimacy of utterance that lies at the heart of the Chopin mazurka. However this was a consistent view of them and pianistically if not poetically very satisfying.

To be honest I could not wait to hear the development of one of the most mature, stylish and musically perceptive pianist of the competition, she who presents Chopin as a grand maitre of the keyboard. After all Chopin himself, that Ariel of the keyboard, liked above most of his pupils, the 'masculine' playing of his music by the heavyweight German pianist and composer Adolf Gutmann (1819-1882), much to everyone's confusion at the time.

Mazurkas, Op. 59

Avdeeva approached the Op.59 Mazurkas with a noble melodic line rather than in any sense indicating they arose from a more rustic Mazovian conception. In No.1 I found this nostalgic mazurka possessed an eloquent cantabile line but was slightly sentimental and over-pedalled. She presented No. 2 and No.3 as grand works with a noble, rather grand tone. All well and good but for me this was somewhat misplaced and rather inflated their proportions beyond the simplicity and intimacy of utterance that lies at the heart of the Chopin mazurka. However this was a consistent view of them and pianistically if not poetically very satisfying.

Piano Sonata in B minor

I anticipated a rather 'symphonic' approach and was satisfied in this expectation when the first movement opened in an exalted Allegro maestoso statement of regal proportions. The movement has the nature of a Ballade. The opening was certainly appropriately noble here and majestic for this great masterpiece. Her cantabile was honed to the perfection of song. Avdeeva plays in a truly aristocratic manner with superbly expressive, blue-blooded tone of great self-confidence and pride. Her rubato is affecting and just the sheer number of subtle pianistic 'things' she does at the keyboard is so imaginative - a complete piano technique - all degrees of staccato up to staccatissimo, a wide dynamic range, a caressing legato, the correct durations of notes were all carefully observed. Avdeeva is also tremendously intense emotionally and utterly convincing. Chopin gives us a vision of a turbulent emotions which veer wildly between courageous strength and self-confidence in the face of the sudden reversals and obstacles life offers us and the lyricism of contemplated beauty and resignation.

The Scherzo was light, airy and breathtakingly virtuosic. A vision surely from from the realm of A Midsummer Night’s Dream than from the world of deeper disillusionment.

The powerful introduction to reality in the Largo begins to mine the depths of the heart and soul. It is an extended aria, in fact a true nocturne. It is a long, self-absorbed meditation. Avdeeva managed this extended time scale magnificently and with convincing examination of conscience and all the questions that process raises. With all the scandals surrounding Chopin's private life swirling with innuendo and the affair with George Sand, it is easy to forget he was a devout Catholic.

Avdeeva adopted the 'correct' Presto non tanto tempo, the proviso Chopin appended to the Finale. Hers was an authoritative performance with exactly the correct degree of hurling impetus. However on occasion she interrupted this avalanche with reflective passages which for me interrupted the drive to the climacteric. Must look at the score again! Thereafter, in this constant Presto she gathered the expression of emotional distress of this 'frenzied, electrifying music, inspired (perhaps) by the finale of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony' (Tomaszewski). Nothing prevents the inexorable headlong rush of this Ballade-like narrative. A truly magisterial passionate performance of this sonata from Avdeeva.

One scarcely wonders that the Sonata’s finale has inspired countless interpreters and commentators. For the writer on Chopin Marceli Antoni Szulc, the movement brought to mind an image of the Cossack Hetman Mazzepa tied backwards on a wild steed chased by the wind. Some saw it as demonic. One typically English commentator of the period felt it went 'beyond the bounds of decency'. In the opinion of Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, ‘In the B minor Sonata, Chopin’s music reaches its culmination’. For the more perceptive English musicologist and collector Arthur Hedley ‘Its four movements contain some of the finest music ever written for the piano’.

It was late autumn 1844 when Chopin put the finishing touches to this work, which he published the following year with a dedication to Countess Emilie de Perthuis, one of his titled lady pupils.

Robert SchumannFantasiestücke, Op. 12

In the Phantasiestucke op.12 (1837) the composer was inspired by the novellas entitled Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier by his beloved author of horror tales and the gothic, E.T.A Hofmann. Incidentally, Hofmann came to live in Warsaw from 1804 to 1807. He assimilated well into Polish society. The years spent in Prussian Poland were some of the happiest of his life. In Warsaw he found the same atmosphere he had enjoyed in Berlin.

Avdeeva brought characterful and imaginative playing to many of these pieces. I could analyse each piece in turn but feel compelled to highlight the opening Das Abends (In the Evening) so lyrical and sensitive a portrait of Eusebius/Schumann himself, suffused with the dreamy light of dusk. Then Aufschwung (Soaring) represented Florestan (Beethoven - Fidelio) and his wilder passions. This I felt slightly rushed. Warum (Why?) sensitively questioning but bordering on a Chopinesque view of Schumann. Grillen (Whims) was not sufficiently mercurial, too solidly grounded for Schumann with little variation of internal tone however rhythmically breathtaking. In der Nacht (In the Night) she brought together Eusebius and Florestan, alternating rhapsodic passion with nighttime serenity. In Fabel (Fable) she captured the whimsical, mercurial aspects of Schumann but seemed to be lacking in humour. The difficult and intense rhythms of Traumes Wirren (Dream's Confusions) were accomplished with the great virtuosity but the entire piece could have been more expressive I felt. The final Ende von Lied (End of the Song) marked Mit guten Humor - the joy of wedding bells followed by painful anxiety as Schumann noted. Avdeeva approached this as a purely virtuoso piano work with some mannerisms, which omitted deeper emotional repercussions.

Fantasy in C major, Op. 15, D 760 (Der Wanderer)

She then embarked on the great Schubert Wanderer Fantasy. I felt she unfortunately had limited understanding of this work. Much of her playing could be described in the words of C.P.E Bach in his Versuch über die wahre Art das Klavier zu spielen 1753 (Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments) ‘They overwhelm our hearing without satisfying it and stun the mind without moving it.’ The dynamic only occasionally fell below forte or fortissimo except in the more lyrical, reflective central sections. However the ‘interpretation’, such as it was, for me displayed extraordinarily limited understanding of Schubert’s intentions in this piece – the operatic nature of ‘The Wanderer’ passing thorough varied landscapes and the joyful and bitter experiences of life on his great journey through it. He wrote it in 1822 only six years before his premature death. The work is surely a keyboard version of what might have been another great Schubert song cycle. The main theme in a hardly festive C-sharp minor is actually taken from his song Der Wanderer. Terribly disappointing as Avdeeva is a brilliant musician with a towering technique to match. Perhaps more background research on such great works before performance if I may be rather presumptuous as I am sure she must have examined the background of the work in detail.