80th Anniversary Programme Duszniki Zdrój International Chopin Festival , Poland. 1 - 9 August 2025. Detailed reviews of fourteen past festival posts (2010 - 2024)

|

Duszniki Zdrój formerly Bad Reinerz in Silesia

Please read and remember as we continue the intense enjoyment of this creative side of the coin of human nature

World-renowned musicians and pianists have been assembled to play at the

80th Anniversary

Duszniki-Zdrój International Chopin Festival

1-9 August 2025

Detailed Program

The book of the festival in both English and Polish with detailed artists biographies and detailed programmes plus interesting essays on Chopin and quotations from his letters are available to download here. Simply too detailed to post here

https://app.box.com/s/8kqacwwufq3zr70ekldbxja8o3jp4s1z

Official Website: http://festival.pl/en/front-english/

The biography and tragically cancelled brilliant, imaginative, unique and fascinating recital programme intended to be given by Sergei Babayan on August 2 appears below at the beginning of these reviews

Cancelled due to illness

You will

need to scroll down

|

The Chopin Manor where the recitals take place |

Recital Reviews

Photographer: Szymon Korzuch

Profile of the Reviewer Michael Moran : https://en.gravatar.c atom/mjcmoran#pic-0

Reviews have been posted in reverse order of live performance (latest recital first) to save listeners the labour of scrolling down after each recital to read the latest review

Many people have mentioned that my reviews are, in the current mnemonic, TLTR (Too Long To Read). With some reluctance I shall try to reduce the length to accommodate reading on a mobile phone which seems to be the ubiquitous technology for much of life's activities in 2025. With my conviction of the prime importance of social, historical and creational context in assessing compositions and composers prior to the performer's interpretation, I will find this rather difficult but needs must I suppose.

* * * * * * * * *

The drive to Duszniki from Warsaw is far more comfortable than years ago (460 kms 5-6 hour drive). Having successfully surmounted a worrying house alarm glitch, I pressed on. However there were wild storms on the way with torrential rain and periods of glorious sun and blue sky - climate change turbulence ? The spray thrown up by vast lorries made life more than a little complicated for this GT driver. Taking a leaf from the behavioral road book of Michelangeli, Karajan and Rachmaninoff, but singularly and sadly lacking even the merest shadow of their musical genius, I at least drove a shared passion, my Jaguar XKR.

Plenty of time now to prepare for the festival ! There is no heatwave here, in fact it is rather cold especially at night and showers much of the day. This has changed to constant warm sunshine (12 August).

Incidentally, I have been reading a fascinating book (in English translation by the indefatigable John Comber) recently published by the NIFC (National Chopin Institute) entitled Chopin's Travels. The volume was written and edited from many unknown primary sources by Henryk F. Nowaczyk. Among many other recondite subjects, formerly 'hidden details' of Chopin's journey to Duszniki Zdroj, are contained in the riveting chapter The summer of 1826 in Reinerz and are of immense interest. Bad Reinerz was the name of the Silesian spa Chopin visited long before the geographical reassignments of World War II.

https://sklep.nifc.pl/en/produkt/77460-chopins-travels-glosses-to-a-biography

Final concert

AUGUST 9 8.00 PM

KATE LIU

Pianist Kate Liu has garnered international recognition, notably winning

the third prize in the 17th International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition

in Warsaw, Poland. She also received the Best Mazurka Prize, as well as the

Audience Favourite Prize awarded by the Polish public through Polish Radio.

Since then, she has toured internationally, performing at some of the world’s

most renowned venues and collaborating with orchestras around the globe.

As a distinguished soloist, Kate has been presented in numerous prestigious

halls, including the Seoul Arts Center, Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre, Warsaw

Philharmonic, La Maison Symphonique de Montréal, Carnegie Hall’s Weill

Recital Hall, Severance Hall in Cleveland, Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.,

Shanghai Concert Hall, Osaka Symphony Hall, and the Phillips Collection. Esteemed

orchestras she has collaborated with include the Warsaw Philharmonic,

Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra,

Cleveland Orchestra, Daegu Symphony Orchestra, Rochester Philharmonic,

Hilton and Head Symphony Orchestra. She is a regular invitee to the ‘Chopin

and His Europe’ Festival in Warsaw, and in 2024 she was the recipient of the

Olivier Berggruen Prize as part of the Gstaad Menuhin Festival.

In 2025, she released her debut album featuring Beethoven and Brahms

sonatas with Orchid Classics.

Born in Singapore, Kate began her piano studies at the age of four and

relocated to the United States at age eight. She studied at the Music Institute

of Chicago under Emilio del Rosario, Micah Yui, and Alan Chow. Early in

her career, she achieved first prizes in the Third Asia-Pacific International

Chopin Competition and the New York International Piano Competition.

Kate holds a bachelor’s degree from the Curtis Institute of Music, as well as

a master’s and Artist Diploma from The Juilliard School, where she studied

with Robert McDonald and Yoheved Kaplinsky.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

Nocturne in F- Major Op. 15 No. 1 (1830–1832)

James Huneker (1857-1921), the renowned American music critic, writer and pianist, author of a book devoted to Chopin, wrote of the Nocturne genre:

‘Something of Chopin’s delicate, tender warmth and spiritual voice is lost in larger spaces. In a small auditorium, and from the fingers of a sympathetic pianist, the nocturnes should be heard, that their intimate, night side may be revealed. […] They are essentially for the twilight, for solitary enclosures, where their still, mysterious tones […] become eloquent and disclose the poetry and pain of their creator.’

The Nocturnes surely must be imagined as a musical poetic reflection and internal emotional agitation that takes place at night when the imaginative mind operates in relative silence and isolation at a different and sometimes fantastical level of consciousness. Chopin lived in a world without electricity. Just imagine this for a moment … The Nocturnes should retain a sense of improvisation in the internal exploration and discovery of sensibility.

The first dozen bars of the Nocturne in F minor Op.15 No.1 were written into the album of Elizabeth Sheremetev. The opening theme is melancholic and elegiac in which Liu adopted a contemplative tempo and ‘sang’ affectingly on the piano. The moment she begins to play we are convinced of her musicality and more than that. This delicate, fey lady is a musical phenomenon and an extraordinary pianist. I have written of her remarkable recitals often over the years on this website.

During the 17th International Fryderyk Chopin Competition, Warsaw, 1-23 October 2015 she was placed 3rd. At that time I had the curious vision of an immensely precocious Chopin savant whilst listening and watching her. Without doubt, hers always becomes one of the most extraordinary Chopin recitals. This pianist seems to be in touch with some force outside of herself, transfigured by the music magnetically and metaphysically, taken over by a musical 'voice' and almost cosmic natural force, if that does not sound too fanciful. She connects us to 'The force that through the green fuse drives the flower' in the words of that great Welsh poet Dylan Thomas.

Listening to her I was reminded of a description of a Chopin performance. In Paris he acquired new aristocratic students in 1847 such as the immensely talented Maria Aleksandrovna von Harder (1833-1880), a precocious 14-year-old Russian-German pianist from Saint Petersburg. She took lessons from Chopin almost every day during 1847 and up to his departure for England in April 1848.

She wrote: '....when he was in pain, Chopin often gave lessons by listening in the office adjacent to the drawing-room .... his hearing, sensitive to the subtlest shadings, immediately recognized which finger was on a given key.' In 1853 Hans von Bülow described her playing to Liszt, an approach that she surely must have partly imbibed from Chopin '...one of a kind . . . full of all the whispers . . . phenomenal, transient and sudden changes in tempo, unlike what you usually hear in concert halls. Luminous, interwoven, wonderful melodies emerged like miraculous swan songs.'

Nadia Boulanger was once asked what made a great as opposed to an excellent performance of a piano work. She answered 'I cannot tell you that. It is something I cannot describe in words. A magical element descends.' This is certainly the case with Kate Liu.

This atmosphere of poetic nostalgia in this nocturne soon gave way to a depiction of the dark night of the soul and turbulent emotions. The contrast in atmosphere was profoundly meaningful and at times intensely lyrical. Liu seemed to explore the darker regions of the heart in a dramatic fashion. These agitated passages led the narrative back into the melancholy aura from which they emerged.

Berceuse in D-Flat Major Op. 57 (1844)

This work can surely be considered ‘music of the evening and the night’. The Chopin Berceuse is possibly the most beautiful lullaby in absolute music ever written. The manuscript of this cradle-song masterpiece belonged to Chopin's close friend Pauline Viardot, the French mezzo-soprano and composer.

Perhaps this innocent, delicate and tender music was inspired by his concern with her infant daughter Louisette. George Sand wrote in a letter ‘Chopin adores her and spends his time kissing her on the hands’ Perhaps the baby caused Chopin to become nostalgic for his own family or even reflect on a child of his own that could only ever remain an occupant of his imagination.

Liu's interpretation with her sensitive and musical fingers, contained a poignant tenderness, refinement and poetry replete with the purity of innocence. The work hovers hesitatingly between piano and pianissimo.

The Berceuse, composed and completed at romantic Nohant in 1844, appears to constitute a distant echo of a song that Chopin’s mother sang to him: the romance of Laura and Philo, ‘Już miesiąc zeszedł, psy się uśpiły’ [The moon now has risen, the dogs are asleep]. (Tomaszewski). In view of this tender genesis of infancy, it is well known Chopin loved children and they loved him.

For me the work does speak of a haunted yearning for his own child, a lullaby performed in his sublimely imaginative mind, isolated and alone. No, not a common feeling about the work and possibly over-interpreted on my part, but what of that ....

|

| The Black Lake - Duszniki Zdroj |

Sonata in B-Flat Minor, Op. 35 (1839)

The great Polish musicologist Tomaszewski describes the opening movement of this sonata Grave. Doppio movimento perceptively: ‘The Sonata was written in the atmosphere of a passion newly manifest, but frozen by the threat of death.’ A deep existential dilemma for Chopin speaks from these pages written in Nohant in 1839. The pianist, like all of us, must go one dimension deeper to plumb the terrifying abyss that this sonata opens at our feet.

Grave-doppio movimento

Liu was not hesitant is conceiving a train of melancholic thought from the outset. The 'Grave' indication was not cursorily executed but set an appropriate tone in granite tempo and deliberation for the entire work. One felt it was the disturbed mind facing the reality of death. The doppio movimento contained within immense dark thoughts and żal, confronting us with our demise. żal, an untranslatable Polish word in this context, meaning melancholic regret leading to a mixture of passionate resistance, resentment and anger in the face of unavoidable fate. Here we were occupied in musical imagination with a moderate yet horrified contemplation that was profoundly atmospheric in its contrast of dreams and grim reality - much the way life presents itself.

Scherzo

'In the midst of life we are in death' emerged as an undiminished sentiment, a message only temporarily assuaged by the lyric and poetic contrasting nature of the Trio. I felt that Liu was miraculously expanding this entire work to monumental proportions.

Marche funébre

Liu gave particularly long silences between movements which gave time for reflection and to fully absorb the dark emotions and implications about to be unfolded before us. The deliberate tempo gave immense existential weight to the utterance, avoiding the customary inflated dynamics for the crude, operatic effects. The lyrical cantabile possessed a true feeling of the desperate reality of memory and dream. Liu created an astonishing sense of floating mystically above reality in the dream world of scarcely graspable recollection.

The effect she created was hypnotic and immanent. The return to cavernous reality was as if we had been thrust down, down into a deep, lugubrious water of the well of grim reality. This was not a 'performance' of the work in essence but a living experience that drew you into its orbit of tragedy and the true nature of human destiny.

Finale. Presto

I felt this movement more as a frantic, hysterical panic of the mind, the disorientated mental reaction in the face of death. 'Wind over the graves' is far too prosaic an interpretation. More a musical stream of consciousness expressed in baroque counterpoint of superb virtuosity.

This was a most remarkable

transcendental performance of a familiar sonata that transported this listener

at least into a far more profound dimension of feeling and existential significance than

the conventional interpretations we are accustomed to hearing.

INTERMISSION

ERIC LU 9.00 PM

Eric Lu won the first prize at the Leeds International Piano Competition in 2018,

at the age of 20. The following year, he signed an exclusive contract with Warner

Classics and has since collaborated with some of the world ’s most prestigious

orchestras and presented in major recital venues. Recent and forthcoming

orchestral collaborations include the London Symphony, Chicago Symphony,

Boston Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Diego Symphony, Seattle

Symphony, Vancouver Symphony, Oslo Philharmonic, Finnish Radio Symphony,

Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic,

Swedish Chamber Orchestra, Helsinki Philharmonic, Orchestre National

de Lille, Royal Philharmonic, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Bournemouth

Symphony, Iceland Symphony, Tokyo Symphony, Shanghai Symphony at

the Proms, and Yomiuri Nippon Symphony, amongst others. Conductors he

collaborates with include Riccardo Muti, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, Ryan Bancroft,

Marin Alsop, Duncan Ward, Vasily Petrenko, Edward Gardner, Sir Mark Elder,

Thomas Dausgaard, Ruth Reinhardt, Earl Lee, Nuno Coelho, and Martin Fröst.

Active as a recitalist, he is presented on stages including the Cologne

Philharmonie, Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Queen Elizabeth Hall in London,

Leipzig Gewandhaus, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, San Francisco Davies Hall,

Cal Performances, Aspen Music Festival, BOZAR Brussels, Fondation Louis

Vuitton Paris, 92nd St Y in New York, Seoul Arts Center, Chopin and his Europe

Festival, Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall and Sala São Paulo. In 2024, he

appeared for the sixth consecutive year in recital at Wigmore Hall London.

Eric ’s third album on Warner Classics was released in December 2022,

featuring Schubert Sonatas D. 959 and 784. It was met with worldwide critical

acclaim and named Instrumental Choice by BBC Music Magazine ’s, which

wrote, ‘Lu’s place among today ’s Schubertians is confirmed’. His previous

album of the Chopin 24 Preludes and Schumann ’s Geistervariationen was

hailed as ‘truly magical’ by International Piano.

Born in Massachusetts in 1997, Eric Lu first came to international attention

as a prize-winner of the 2015 Chopin International Competition in Warsaw,

aged just 17. He was also awarded the International German Piano Award in

2017 and Avery Fisher Career Grant in 2021. Eric was a BBC New Generation

Artist in 2019–2022. He is a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, studying

with Robert McDonald and Jonathan Biss. He was also a pupil of Đặng Thái

Sơn and has been mentored by Mitsuko Uchida and Imogen Cooper. He is

now based in Berlin and Boston.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

I think I am gradually beginning to grasp the mysteries of Chopin's Polish mazurkas, which variety of Mazovian dance (Mazur, Kujawiak and Oberek) to identify, which rhythm and mood, be it nostalgic, rumbustious or otherwise. A little info about the Mazurkas was included in the “Chopin Express”, Issue 13 (October 2010) by its editor Krzysztof Komarnicki :

A trap called 'Mazurka'

Chopin’s

Mazurkas are a mixture of simplicity and subtlety. They are drawn from a folk

pattern but are full of nuances that must be executed properly, or else

artistic disaster is just round the corner. What are the dangers, then?

You cannot properly play a dance you have never danced. You need to know where a leap and when a landing is, and you must remember that a dancer can’t stop in mid air. “Mazurka” actually describes the group of dances consisting of Mazur, Kujawiak and Oberek. Each species has different steps, tempos and accents. You need to know and recognize each one, as Chopin often makes use of all of them within a single movement.

Mazurkas

are notated in 3/4 time, like waltzes, but you play them in a different way –

the trick is to put the accents in the right places. Rhythm is another trap:

Chopin notates similar rhythms with or without rests, and you play those

differently: the dancers have their feet on ground where there are no rests,

and they jump if the rests are present.

Polish folk music knows no polyphony. Chopin was well aware of that, but sometimes there are several melodies sounding at the same time, as if his mind was teeming with musical thoughts. It is not counterpoint in the sense of Bach.

Mazurkas, Op. 56 (1843–1844)

In 1843, Chopin composed three new mazurkas. They delight us but are often surprising.

No. 1 in B Major

Lu interpreted this nostalgically in terms of reminiscent thoughts passing through the mind, fragments of memories magically bound together.

No. 2 in C Major

Lu brought out the intensely rustic character of this mazurka. Ferdynand Hoesick - Polish bookseller and publisher, writer, literary historian, and musicographer (1867-1941) described it as follows: ‘The basses bellow, the strings go hell for leather, the lads dance with the lasses and they all but wreck the inn’.

No. 3 in C Minor

This mazurka has the character and shape of a dance poem. Lu presented the nostalgic reflections with strong memories of the dance dominating the themes which emerge organically from one another. He expressed the polyphony here with rare musical perception.

Piano Sonata in B Minor, Op. 58 (1844)

This sonata is one of the greatest masterpieces in the canon of Western piano music. Lu opened the sonata dramatically and polyphonically but with immense clarity and controlled power which is a hallmark of his execution at the keyboard. The opening Allegro maestoso was dramatic but revealed poetry and moving lyricism. One should feel that Chopin was embracing the cusp of Romanticism, yet at the same time hearkening back to classical restraint - le climat de Chopin as his favourite pupil Marcelina Czartoryska described it. The Trio did have a beautiful legato cantabile that made the piano sing.

The Scherzo revealed all the glistening articulation Lu was capable of being energetic with a Mendelssohnian atmosphere of Queen Mab fairy lightness. The Trio again displayed a warm Chopin cantabile.

The transition to the Largo was not sufficiently expressive and Lu was rather heavy for my conception. Here, however, we began with him an exquisite extended nocturne-like musical voyage taken through a night of meditation and introspective thought. This great musical narrative, an emotional landscape we travelled through, an extended and challenging harmonic structure, was presented as a poem of the reflective heart and spirit. I felt his playing was tonally refined and transported us with spiritual introspection, enveloping us in a mellifluous dream world.

The Finale. Presto ma non tanto was certainly a tremendously powerful expression in its headlong flight though the threats and obstacles that life heartlessly throws up before us. He approached this movement with tremendous virtuosity which benefits its emotional impact, not unlike a rhapsodic narrative Ballade in character. Again Tomaszewski cannot be bettered:

Thereafter, in a constant Presto (ma non troppo) tempo and with the expression of emotional perturbation (agitato), this frenzied, electrifying music, inspired (perhaps) by the finale of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony…’

Rondo in C Major, Op. 73 for two pianos (1828)

It is so rare to hear this sparkling work for two pianos, especially performed by two outstanding artists such as Kate Liu and Eric Lu. I heard it once before at Duszniki in August 2022 with Lucas & Arthur Jussen.

With Elsner (Chopin's teacher), composition studies began with the polonaise, but it was immediately followed by rondos and variations (Tomaszewski)

As we have seen, in 1825 the fifteen year old Chopin wrote and published his first rondo. As a young man, he was composing in the glittering and Hummel-influenced, modish style brillante. These early works (along with others) are utterly delightful, graceful and charming to my mind and do not deserve to be downgraded by 'serious commentators' as simply youthful, virtuosic pieces demonstrating the ‘classical’ aspect of his compositional training in Warsaw. They are being presently being resuscitated.

This 1828 Rondo in the version for two pianos demonstrated once again the extraordinary audience communication and synchronization of this 'family' duo. Eric and Kate brought all the delight I was searching for in this unashamedly joyful, style brillante, music-making work. The virtuosic display element remained elegant and refined in the musical writing. I found the cantabile and figurative writing quite wonderful in Chopin's youthful attachment to extrovert display at the keyboard. This was taken full advantage of by the spontaneous character and electrical energy of these two artists. A highly entertaining and musical performance that lifted the spirits out of the 'slough of despond' into which the planet has fallen! Wild audience response!

AUGUST 9 4.00

KRZYSZTOF WIERCIŃSKI

Fryderyk

Chopin (1810–1849)

Rondo in

C minor Op.1 (1825)

This rarely performed

youthful work was an absolute delight. In a rather remarkable and inspired

decision (to my mind) decision, he decided to present it. This work was

written by fifteen-year-old ‘Frycek’ and published in 1825. The rondos indicate

familiarity with the rondos of the Viennese Classics by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven

and lesser luminaries. The work was dedicated to the wife of the Lyceum

rector, Samuel Bogumił Linde. It was profitably lithographed by Antoni

Brzesina, the principal music retailer and publisher in Warsaw since the establishment

of the Congress Kingdom. So Chopin even in his early work had premonitions of financial

reward from his compositions.

The dazzling and

fashionable style brillante was somewhat of an obsession with

the young pianist Fryderyk on the pianos of the day. However, later in life the

scherzos, ballades and études avoided the genre of the free-standing rondo.

They are now considered as youthful or virtuosic pieces indicating the

‘classical’ aura of his training in composition.

This is not to say they

should be glided over without due attention. There is evidence that his later mature

work was influenced by these early forays into glittering virtuoso passagework

and figuration. His later harmonic embellishments and rich ornamentation hark

back to his earliest work and traces were carries over. Also the contrasting

sections indicate structural similarities later in his compositional style. The

youthful compositions are more recently being given more serious and deserved

attention. Young Chopin observed features of the style brillante in

rondos by the gloriously blithe Hummel and also Weber. This gave him the model

for shaping the pianistic luster of his own works

This Op.1 Rondo is already marked by graceful, elegant and brilliant writing and can be highly entertaining if performed with the correct feel for context and period. All of this was achieved by Krzysztof Wierciński. He had a fine sense of period style, scintillating articulation and transparent polyphony. There was a great deal of sparkling youthful energy and sound. Krzysztof Wierciński brought the alluring, sparkling tone and refined touch of the style brillante to the work convincingly. He was charming, elegant and stylish

It was clear that

Krszysztof had a cultivated taste for the youthful Chopin brought up in an

entirely aristocratic environment in early nineteenth-century Warsaw.

Preludes

from Op. 28 (1838–1839)

No. 19

in E-Flat Major

This

approach I found somewhat conventional but none the worse for that

No. 20

in C Minor

Many alternative

approaches are possible here

No. 21

in B-Flat Major

I found

myself searching for more character and personal expression in his presentation

No. 22

in G Minor

A forceful

and authoritative presentation which was correct and appropriate

No. 23

in F Major

This interpretation

was beautifully expressive

No. 24

in D Minor

The

psychological turbulence he brought to this interpretation was compositely

convincing

Prelude

in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 45 (1841)

A

sensitive melancholic atmosphere that was emotionally appropriate was created

by Krzysztof Wierciński

with a particularly alluring and refined conclusion ppp

Waltzes, Op.

64 (1847)

He is one

of the few young pianists I have heard that instinctively understands the

slight affectation and idiomatic rhythm associated with Chopin waltz.

No. 1

in D-Flat Major

Excellent

interpretation - amusingly stylish and accurate

No. 2

in C-Sharp Minor

Pleasantly

expressive with attractive evidence of a personal vision

No. 3

in A-Flat Major

An expressive interpretation replete with

hopes and memories

Scherzo

in B-flat minor Op.31 (1836)

This Scherzo is

a marvelously dramatic work with an authentic feeling of narrative

and complex swings of mood and heightened emotion coupled with

poetic meditation.

Krzysztof Wierciński presented this work as a truly electrifying

drama. His LH was particularly strong and the urgency he conjured up became

irresistible. I felt the extended triplet had particular urgency

The brilliant Polish musicologist

Mieczyslaw Tomaszewski writes of this scherzo: 'The new style, all Chopin’s

own, which might be called a specifically Chopinian dynamic romanticism, not

only revealed itself, but established itself. It manifested itself à la Janus,

with two faces: the deep-felt lyricism of the Nocturnes Op.27 and the

concentrated drama of the Scherzo in B flat minor.' Friedrich Niecks,

the German musical scholar and author, found the Trio evocative of

the Mona Lisa’s thoughtfulness, a mood full of longing and

wondering.

Arthur Hedley thought about the work’s ecstatic lyricism,

before concluding in a way even more appropriate today in the age of

recording: ‘Excessive performance may have dimmed the brightness of

this work, but should not blind us to its merits as thrilling and convincing

music.’

Jean-Jaques Eigeldinger in the Chopin 'bible' Chopin -

Pianist and Teacher as seen by his pupils mentions on p.84-85:

The repeated triplet group that appears so simple and innocent

could scarcely ever be played to Chopin's satisfaction. 'It must be a

question' taught Chopin. He felt it never played questioningly enough,

never soft enough, never round enough (tombé), as he said, never

sufficiently weighted (important). 'It must be a house of the dead',

he once said [...in his lessons]

I saw Chopin dwell at length on this bar and again at each of its appearances. Is this a question by Hamlet with a tempestuous but ambiguous answer ? 'That is the key to the whole piece,' he would say yet the triplet group is generally snatched or swallowed. Chopin was just as exacting over the simple quaver accompaniment of the cantilena as well as the cantilena itself. 'You should think of [the singer] Pasta, of Italian song! - not of French Vaudeville.' he said one day with more than a touch of irony.' [his pupil Wilhelm von Lenz]

Vanessa Latache (Head of Keyboard at the Royal College of Music, London) in an illuminating masterclass on this Scherzo at Duszniki in August 2022 with Krzysztof Wierciński, observed that the notes of any musical work 'need to lift off the page'. The opening triplet as an existential, even diabolical question.

At the time of composition this work must have been deeply shocking and revolutionary. Frederick Niecks quotes Robert Schumann who wrote of the Chopin Scherzos (the Italian word scherzo meaning 'joke') 'How is 'gravity' to clothe itself if 'jest' goes about in dark veils?'. She advised utilizing a degree of capriciousness to create the emotional ambiguity often present at the centre of Chopin's energetic despair. Think horizontally not vertically and harmonically in cantabile and chorale sections.

As an encore he captured the Chopin Grande valtz brillante in E-flat major Op.18 with excellent rhythm, style, sparkle, elegance and tremendous verve. A most enjoyable, even outstanding performance with a deep understanding of Chopin, which in fact applied to the entire recital. A particularly promising young pianist.

INTERMISSION

5.00 PM

MATEUSZ DUBIEL

Having graduated in 2023 from Anna Skarbowska’s piano class at secondary

music school in his home city of Bielsko-Biała, the artist is now studying with

Mirosław Herbowski at the Krzysztof Penderecki Academy of Music in Cracow.

Dubiel is the winner of the 51st and 53rd National Fryderyk Chopin Piano

Competitions in Warsaw (2022, 2025) as well as of several international

competitions for young pianists, including ‘Arthur Rubinstein in Memoriam’

(Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2021), ‘Jeune Chopin’ (Lugano, Switzerland, 2023), and

the Baltic Competition in Gdańsk (2023). He has participated in masterclasses

taught by Profs Michel Beroff, Piotr Paleczny, Kevin Kenner, Andrzej Jasiński,

Arie Vardi, and Angela Hewitt.

The artist has played recitals at home and abroad, including at Warsaw’s

Royal Castle, the Birthplace of Fryderyk Chopin at Żelazowa Wola, the

Krzysztof Penderecki European Centre for Music in Lusławice, Cavatina Hall

in Bielsko-Biała, the Pomeranian Philharmonic in Bydgoszcz, as well as in

Japan, the United States, Paris, Vilnius, Hamburg, Cologne, and on Majorca.

He has appeared in Polish Radio Chopin’s Marathon of Chopin’s Music as well

as at the Young Pianists’ Chopin Interpretations Festival in Konin-Żychlin,

where he won the 1st prize (2022).

His accolades include the IKAR Award for Culture and Art from the President

of Bielsko Biała City (2021), scholarships from the Polish Children’s

Fund, the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, and the ‘Young Poland’

programme.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

Mazurkas Op. 41 (1838–39)

A few general thoughts concerning Chopin mazurkas in general as they are such a vital musical form to penetrate to the heart of this composer. I feel the mazurkas are recalled dances, memories of past joys with a significant weight of melancholic nostalgia. These reminiscences of dance and associated experience are all viewed through the obscuring veils of past time, a musical À la recherche du temps perdu. The gauze of memory descends. The mazurkas were published as sets and Chopin himself may have had some organizational musical mystique, a musical or philosophical connection in grouping them together in their compositional arrangement in collections.

Of course Chopin was a perfect mimic, actor, practical joker and enthusiastic dancer as a young man, tremendously high-spirited. He once wrote a verse describing how he spent a wild night, half of which was dancing and the other half playing pranks and dances on the piano for his friends. They had great fun! One of his friends took to the floor pretending to be a sheep! On one occasion he even sprained his ankle he was dancing so vigorously.

He would play with gusto and 'start thundering out mazurkas, waltzes and polkas'. When tired and wanting to dance, he would pass the piano over to 'a humbler replacement'. Is it so surprising his teacher Józef Elzner and his doctors advised a period of 'rehab' at Duszniki Zdrój to preserve his health which had already begun to show the first signs of failing? This advice may not have been the best for him, his sister Emilia and Ludwika Skarbek, as reinfection was always a strong possibility there. Both had died not long after their return from the 'cure'.

Many of his mazurkas would have come to life on the dance floor as improvisations. Perhaps only later were they committed to the more permanent art form on paper under the influence and advice of the Polish folklorist and composer Oskar Kolberg. Chopin floated between popular and art music quite effortlessly.

No. 1 in E minor

Chopin composed mazurkas all his life. The great Polish musicologist Tomaszewski tells us that In the E minor Mazurka we hear a distinct Polish echo: the melody of a song about an uhlan (cavalry) and his girl, ‘Tam na błoniu błyszczy kwiecie’ [Flowers sparkling on the common] (written by Count Wenzel Gallenberg, with words by Franciszek Kowalski) – a song that during the insurrection in Poland had been among the most popular. Chopin quoted it almost literally. Dubiel captured the nostalgia of remembrance so common in Chopin's music successfully, also when Chopin heightened the drama to the tragic.

No. 2 in B major

The Mazurka in B major was most likely composed at Nohant, although bears a feeling of the period on Majorca. ‘The first four bars and their repetitions’, said Chopin, ‘are to be played in the style of a guitar prelude, progressively quickening the tempo’. Next to the piano, the guitar was Chopin's favourite instrument and the one that his teacher Elsner chose to serenade him when he left Warsaw by the Wola gate in 1830. I was unsure if Dubiel was aware of the guitar background to the piece when his playing was tonally and so attractively idiomatically pianistic.

No. 3 in A flat major

The euphonious intonations and rhythms of the Cuyavia region, in north-central Poland, situated on the left bank of Vistula inspired Chopin. Dubiel gave a satisfying and idiomatic interpretation of this musical geographical background. Such an attractive, lyrical rhythm.

No. 4 C sharp minor

This piece was composed during the first summer at Nohant. It is one of the most beautiful of Chopin's mazurkas, resembling a miniature dance poem. It seems to arise out of silence and ends the same way.

The Hungarian pianist and teacher Stephen Heller (1813-1888) noted: ‘What with others was a refined embellishment, with him was a colourful bloom; what with others was technical fluency, with him resembled the flight of a swallow.'

Dubiel again rendered the poetry of the reminiscence of Chopin warmly as the composer's memory expanded and intensified during the mazurka. He became emotionally involved in his playing which lifted the interpretation above the conventional. The conclusion returned us to the dream from which the piece originally materialized

Scherzo in E Major, Op. 54 (1842–1843)

Then he performed the rarely played Scherzo in E major Op.54. This scherzo is not dramatic in the demonic sense of other scherzi, but lighter in ambiance. The outer sections are a strange exercise in rather joke-filled fun with a darkly concealed centre of passionate grotesquerie. The work mysteriously encloses a deeply felt and ardent nocturne in the form of a longing love poem, suffused with a sense of loss. Dubiel was able to express the complexity of these emotions with conviction and skill. He delighted us both with the beauty of his tone and his lightness of transparent articulation.

Playfulness with hints of seriousness and gravity underlie the exuberant mood of this scherzo. Dubiel maintained this difficult expressive balance very well, only slightly missing the emotional ambiguities that run like a vein though the work. The central section (lento, then sostenuto) in place of the Trio, gives one the impression so often with Chopin, of the ardent, reflective nature of distant love. Dubiel was rather moving in a beautiful but not sentimentally indulgent cantabile which can be so tempting for pianists.

The image of the glittering turtle shell took hold of me in the Scherzo. A variegated surface concealing a complex interior. The internal irrationality and neurotic dislocation evident within this piece tended to escape Dubiel at times as his virtuosity rather dominated the organic life within the piece that the surface carapace was concealing. Chopin seduces one inside his work but one must become sensitive to his gestures. Dubiel yet brought a sense of glowing triumph and the will to continue with life in the passionate, rather glittering phrases that close the work.

Heinrich Heine, a German poet who idolized Chopin, asked himself in a letter from Paris: ‘What is music?’ He answered ‘It is a marvel. It has a place between thought and what is seen; it is a dim mediator between spirit and matter, allied to and differing from both; it is spirit wanting the measure of time and matter which can dispense with space.

Waltz in A-Flat Major, Op. 42 (1840)

A most stylish, elegant and energetic performance with excellent waltz rhythm.

N.B. (A mild but intrusive squealing from a smoke alarm tended to obscure proceedings and possibly broke his concentration for some minutes)

Polonaise-Fantaisie in A-Flat Major, Op. 61 (1845–1846)

The Polonaise-Fantaisie contains all the troubled emotion and desire for strength in the face of the multiple adversities that beset the composer at this late stage in his life. This work, the first in the so-called ‘late style’ of the composer, was written during a period of great suffering and unhappiness. He laboured over its composition. What emerged is one of his most complex of his works both pianistically and emotionally.

Dubiel gave us a thoughtful and brilliant performance of this mature Chopin work in many ways. I could not help reflecting, however, that increased life and musical experience would deepen his appreciation of the extraordinarily varied scenes and feelings, emotional content and reflections, contained within this great work.

Chopin produced many sketches for the Polonaise-Fantaisie and wrestled with the title. He wrote: ‘I’d like to finish something that I don’t yet know what to call’. This uncertainty surely indicates he was embarking on a journey of compositional exploration along untrodden paths. Even Bartok one hundred years later was shocked at its revolutionary nature. The work is an extraordinary mélange of genres and styles in a type of inspired improvisation that yet maintains a magical absolute musical coherence and logic.

Chopin leads us through a succession of extraordinary scenes and events. They pass in successive train through the imagination of any listener or pianist who can selflessly give himself in a meditative trance to this hypnotic music, the composition flickering on the screen of the mind. One has an imaginative experience bordering on the cinematic.

He

completed it in August 1846. The reception was one of confusion and even

upset. As Jachimecki stated: ‘the piano speaks here in a language not

previously known’. Frederick Niecks’s judgment was that the

Polonaise-Fantasy ‘stands, on account of its pathological contents,

outside the sphere of art’.

The Dream

A

change came o’er the spirit of my dream

The

Wanderer was alone as heretofore,

The

beings which surrounded him were gone,

Or

were at war with him; he was a mark

For

blight and desolation, compass’d round

With

Hatred and Contention; Pain was mix’d

In

all which was served up to him, until,

Like

to the Pontic monarch of old days,

He

fed on poisons, and they had no power,

But

were a kind of nutriment; he lived

And

made him friends of mountains: with the stars

And

the quick Spirit of the Universe

(excerpt)

|

Lord Byron's Dream (1827)

|

Tate Gallery London |

Dubiels's encore of the Chopin Berceuse was one of deep tenderness and refinement in tone and touch. He is certainly one of the rising tide of brilliant young Polish pianists in 2025 with a promising future ahead.

24th NATIONAL PIANO MASTERCLASS

9th AUGUST

JAN WEBER CHAMBER MUSIC HALL

10.00 AM

PROF. CLAUDIO MARTÍNEZ-MEHNER

Born in Germany in 1970, Claudio Martínez-Mehner began his music studies

at an early age with Amparo Fuster, Pedro Lerma and Joaquin

Soriano

at the Real Conservatorio Superior de Musica in Madrid. In

addition to his

piano studies, he played the viola in the Spanish National

Youth Orchestra

as well as the violin, viola, and harpsichord in the Chamber

Orchestra of

the German School.

He continued his studies at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in

Moscow and

with Professor Dmitri Bashkirov at the Escuela Superior de

Musica Reina Sofia

in Madrid, afterwards in Germany at the Hochschule fur Musik

in Freiburg

(completing his Master-of-Performance course in 1994), the

Fondazione per

il Pianoforte in Como (Italy), and with Vitaly Margulis and

Leon Fleisher at

the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University in

Baltimore (USA). In

addition, he participated in masterclasses conducted by

Murray Perahia, Fou

Ts’ong, Alexis Weissenberg, Karl-Ulrich Schnabel, Dietrich

Fischer-Dieskau,

Mstislav Rostropovich, and Gyorgy Kurtag, among many others.

For almost

a decade he received invaluable advice from Professor Ferenc

Rados.

At a young age, Claudio Martínez-Mehner won the first prize with special

mention in the German competition ‘Bundeswettbewerb Jugend

Musiziert’.

He reached the finals of the International Piano Competition

Paloma O’Shea

in Santander, Spain (1990) and won first prizes in the

international competitions

Pilar Bayona in Zaragoza, Spain (1992), Fondation Chimay in

Belgium

(1993), and Dino Ciani in Milan, Italy (1993).

As a soloist he has performed in most major cities in

Europe, the United

States, Russia, Central America, Japan and Korea, with

orchestras such as the

Munich Philharmonic, the Moscow Philharmonic, Filarmonica

della Scala, the

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, the Prague Philharmonic, the

Orchestra della

Svizzera Italiana, the Norddeutsche Rundfunk, Philharmonia

Hungarica, and

most major Spanish orchestras. Martínez-Mehner is also an avid chamber

music player, who has performed with numerous ensembles in

Europe and Asia.

At present he is a piano professor at the Hochschule fur

Musik in Basel and

the Hochschule fur Musik und Tanz in Cologne. He teaches

masterclasses in

Europe, Asia, and the USA.

Participant: ANTONI KŁECZEK

Throughout, there were a staggering number of illuminating references to other works by Chopin, the illustrative extracts all played with full spontaneous accurate virtuosity and knowledge from memory! Not only Chopin - Brahms Ballades, Liszt .... Martínez-Mehner is undoubtedly a type of musical genius.

AUGUST 8 8.00 PM

Vocal recital

OLGA

PASICHNYK NATALIA PASICHNYK

(voice) (piano)

OLGA PASICHNYK

She was born into a family of academics in

Ukraine and completed

her vocal studies at Kyiv Conservatory. During her

postgraduate

studies at Warsaw’s Chopin Academy (now

University) of Music, she made

her stage debut at Warsaw Chamber Opera (1992), followed

four years later

by an appearance at the Theatre des Champs Elysees in Paris

as Pamina in

Mozart’s The Magic Flute.

Her repertoire comprises more than fifty highly critically

and publicly

acclaimed parts in operas by Monteverdi, Gluck, Handel,

Mozart, Weber, Bizet,

Rossini, Verdi, Puccini, Debussy, Poulenc, and contemporary

composers, sung

on the world’s most renowned and prestigious stages as well

as recorded for

music labels, the radio, and television. She has appeared at

the Opera National

de Paris – Opera Bastille, Palais Garnier, Theatre des

Champs-Elysees,

Theatre Chatelet, Salle Pleyel in Paris, Concertgebouw Amsterdam,

the Berlin

Komische Oper, Konzerthaus and Philharmonie, Elbphilharmonie

Hamburg,

Teatro Real and Auditorio Nacional de Musica in Madrid, the

Bayerische Staatsoper

and Munchner Philharmonie in Munich, the Palais des

Beaux-Arts

and Theatre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, Theater an der

Wien, Grand

Theatre de Geneve, the Finnish National Opera, the Flemish

Opera, Tokyo

Suntory Hall, Teatr Wielki – the Polish National

Opera in Warsaw, as well as

the Bregenzer Festspiele. She also performs a vast chamber

repertoire and

sings recitals with her pianist sister Natalya Pasichnyk.

Olga has taken part in numerous concerts of symphonic and

oratorio

music in renowned venues throughout Europe as well as in the

United States,

Canada, Israel, China, Japan, and Australia. She has

frequently appeared with

the greatest orchestras, including Boston Symphony, the

Belgian National

Orchestra, the Orquestra Nacional de Espana and Orquesta

Sinfonica de RTVE,

The English Concert, Wiener Symphoniker, Orchestre

Philharmonique de

Radio France, Orchestre National de France, Les Musiciens du

Louvre-Grenoble,

Akademie fur Alte Musik Berlin, the Freiburger

Barockorchester, the

Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century,

Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, and

NDR Bigband, under such masters of the baton as Fabio

Biondi, Ivor Bolton,

Andrzej Boreyko, Frans Bruggen, Jean-Claude Casadesus,

Marcus Creed,

Charles Dutoit, Mark Elder, Rene Jacobs, Vladimir Jurowski,

Roy Goodman,

Christopher Hogwood, Heinz Holliger, Philippe Herreweghe,

Jacek Kaspszyk,

Kazimierz Kord, Jerzy Maksymiuk, Jean-Claude Malgoire, Marc

Minkowski,

John Nelson, Kazushi Ono, Andrew Parrott, Krzysztof

Penderecki, Trevor

Pinnock, Jean-Christophe Spinosi, Marcello Viotti, Antoni

Wit, and Massimo

Zanetti, among others.

The artist has recorded more than sixty CDs and DVDs under

such labels

as CD Accord, Dabringhaus und Grimm (MDG), Harmonia Mundi,

Naxos,

and Opus 111.

NATALIA PASICHNYK

She has given

performances in the most renowned venues throughout

Europe, in the United States, Japan and Argentina. She also

records extensively

for the radio, television, as well as such music labels as

BIS Records,

NAXOS, OPUS 111, Pro Musica Camerata, Musicon, and others.

Her album

Consolation – Forgotten Treasures of the

Ukrainian Soul (BIS

Records) won

the highest critical praise and was hailed by the German Mittelbayerische

Zeitung as Discovery of the Year.

Natalya was Sweden’s first artist to

receive the Gold Medal of Global Music

Awards (2024). She also won prizes in the Fifth Nordic Piano

Competition

in Nyborg (Denmark, 1998), the Cincinnati World Piano

Competition (USA,

1999), and the Umberto Micheli International Piano

Competition in Milan

(Italy, special prize, 2001).

A faculty member and teacher at the Royal College of Music

in Stockholm,

Pasichnyk is a recipient of the prestigious Anders Wall

Music Prize (2000), the

Stockholm City Award for her contributions to the Swedish

capital’s cultural

life (2017), the Church of Sweden’s

Culture Prize for her project Rethinking the

Well-Tempered Clavier, and the Bo Bringborn

Music Prize for her achievements

(2024). She was twice listed by Sweden’s

largest music magazine OPUS (2014,

2022) among the most influential figures in Swedish culture.

Natalya frequently serves on the juries of international

piano competitions

and conducts regular masterclasses. She is the founder (in

2014) and head of

the Ukrainian Institute in Sweden, as well as artistic

director of several music

festivals, including the European Festival ‘Ukrainian

Spring’.

In June 2021, she obtained a DMA doctoral degree for her

project dedicated

to George Crumb’s Makrokosmos,

and in June 2023 – a PhD in artistic studies

from the Grieg Academy at the University of Bergen.

* * * * * * * * *

In this recital I will not analyze the performance of each of the many songs with their music and texts by great and more modest composers and poets, suffice to say they were performed with great sensitivity, elegance, profound musicality and tact.

Also many were affecting and stirring Ukrainian songs with which I am completely unfamiliar. Olga and Natalia Pasichnyk offered them as a tribute and comfort to the victims of the cruel war now in progress.

|

| Olga Pasichnyk |

Fryderyk

Chopin (1810–1849)

/ Pauline Viardot Garcia (1821-1910)

Mazurkas (a selection), set to words by Louis Pomey (1848)

Aime-moi, Op. 33, No. 2

Berceuse, Op. 33, No. 3

Seize ans! Op. 50, No. 2

Coquette, Op. 7, No. 1

The remarkable woman Pauline Viardot, considering her contemporary fame, is a largely forgotten figure today. I will redress this a little if I may, as through her charisma and genius she influenced a great many composers to write in the genre we now so readily refer to as 'Romantic'.

Pauline Viardot was born into a distinguished a extremely famous family of Spanish opera singers. Her father Manuel Garcia was sought after throughout Europe. Pauline showed formidable musical promise and exceptional talent at the piano. She had her heart set on being a concert pianist, being highly praised by her teacher Franz Liszt and also in her compositions and musical theory by Hector Berlioz. A woman composer at this time was highly unusual.

However, much to her regret, her mother steered her away into a singing career as a soprano although she remained an accomplished pianist all her life. In 1839 she made her opera debut to great critical success as Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello in London. She was courted by many famous artists of the day including Alfred de Musset but in the end married Louis Viardot the Director of the Théâtre Italien in Paris in 1840, 21 years her senior.

This marriage arrangement was encouraged by Viardot’s close friend, George Sand, who advised her to marry for financial survival. The marriage, while practical, was a romantic sacrifice for Viardot. She maintained a love affair for most of her adult life with Ivan Turgenev, the Russian author. Some of her most well known songs were transcriptions of 12 Chopin mazurkas. Beyond her song output, Viardot composed four operettas (three with with libretti by Ivan Turgenev), an opera, Cendrillon, chamber music, and several small-scale piano works.

Her singing career blossomed until she became know as 'the enchantress of nations' and after capturing the heart of Turgenev during a season in St. Petersburg in 1843, he took up residence in her home, adoring her till his death! Chopin, Gounod, Saint-Saëns and Berlioz thought her a divine presence on the stage. She held inspiring and famous musical salons for the cognoscenti when the family moved to Baden-Baden. They had remarkable drawing parties together there as a group.

“There is nothing more interesting, nothing more moving than to feel that you have an entire audience in the hollow of your hand, laughing when you laugh, weeping when you sob, and shaking with anger. PAULINE VIARDOT-GARCÍA (1821-1910)

For seven years, between 1839 and 1846, picturesque Nohant near Paris became the summer retreat of Fryderyk Chopin and George Sand. And while Sand conceived novels and plays, Chopin composed. They entertained famous artists such as Franz Liszt, Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, and the painter Eugène Delacroix. One respected and talented guest was this renowned Spanish mezzo-soprano, Pauline Viardot.

The Chopin mazurka transcriptions originated in the summers of 1841-43 and 1845-46 at Nohant, during Viardot’s visits with her husband Louis. These summer holidays were the perfect setting for studying music during the day and organizing 'salon' concerts in the evening. Viardot and Chopin developed a close friendship, based on artistic respect and temperamental affinities. During her visits to Nohant she played duets and studied music with Chopin.

She was fascinated by the Polish language and gave performances of Chopin songs in their original Polish version. Enchanted by the Chopin mazurkas, Viardot arranged a selection of these for voice and piano. She commissioned a minor French poet (Louis Pomey) to write lyrics for a number of them. She, in turn, ornamented and improvised on freely them and the result was a set of beguiling, unashamedly sentimental 'salon' pieces. Chopin and Viardot publicly performed the set in Paris 'salons' and during the composer’s last public appearance in London.

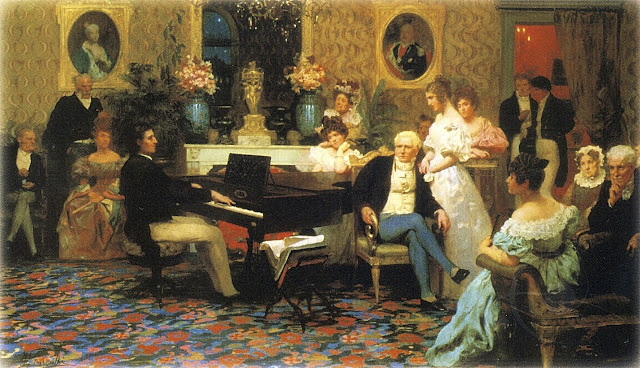

Lieder recitals have become so rare in modern times in comparison to instrumental concerts. This must come from the shocking decline of music-making in the home and the disappearance of the 'salon'. A modern concert hall can never be as conducive to elegant intimacy and poetic reverie as a serious nineteenth century ‘salon’ might have been, seasoned with intellectual conversation, an aristocratic audience, family portraits, paintings, Caucasian rugs, French tapestries and Murano chandeliers.

In time she became a closer friend of Georges Sand at Nohant (Sand based her novel Consuelo on Viardot) and spent many joyful hours there and of course met Chopin often there. A feeling of 'fellow souls' seemed to arise between them as their temperaments had a certain affinity. Chopin admired her playing and gave her piano lessons - compensating somewhat for what she considered her lost vocation. He also advised her on her vocal compositions and her settings of his mazurkas as songs.

She no doubt talked to him about Spanish music and one might speculate that perhaps the inspiration for the Boléro was Chopin's friendship with the French soprano. However, the work does contain Polish polonaise elements and other inspirations have been advanced. The rift between Chopin and Sand in July 1847 put an end to the pastoral idylls Chopin and Viardot enjoyed at Nohant. Pauline tried to get Chopin and Sand back together but...

After Chopin's death Pauline wrote to Georges Sand:

I came to know of his death from strangers who had come to ask me very formally to participate in a Requiem which was to be given at the Madeleine for Chopin. It is then that I realized how deep my affection was for him…. He was a noble soul. I am happy to have known him and to have obtained a little of his friendship.

George Sand failed to attend Chopin’s funeral but Pauline sang from Mozart's Requiem at the graveside as his body was lowered into the earth at Pére-Lachaise in Paris.

Pasiecznyk gave a sensitive, poetic, nostalgic and and times lively performance of all these works. In the small dworek it was not difficult to conjure up the intimate and civilized charms of another age listening to this beautiful voice.

Although

Natalia Pasiecznyk is a fine chamber musician I felt the need of a more

appropriate sound palette on a period instrument to accompany this voice in

this particular repertoire. At Nohant both Chopin and Viardot

would have played Sand's Pleyel pianino. These are superb, intimate and

refined upright pianos. Considering they were a popular domestic instrument

among the affluent citizens and artists of the day (Sand, Delacroix, Mme.

Hanska, Franchomme, Princess Marcelina Czartoryska and countless others owned

them) too often they are neglected as they are visually rather unprepossessing

compared to the Grands.

|

|

|

A rare daguerreotype of Pauline Viardot at the piano |

Pauline

Viardot-Garcia photograph

|

Pierre Petit (1832–1909) French photographer Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849) I have often wondered what prompted Chopin to set the rather undistinguished rustic poetry of Stefan Witwicki (1801-1847) to such beautiful melodies and what it might tell us about his sensibility and taste - but then he was in the bloom of youth. This passionate lover of the operas of Bellini hardly cared for these particular musical children, yet they are moving in a youthfully ardent way. Olga Pasichnyk sang these songs with all the beautiful inflection, poetry and eloquence that years of experience performing them have brought. The lyrical Chopin melodic accompaniment played by Natalia Pasichnyk was subtle and merged to a poignant musical symbiosis with her sister. |

Zyczenie (A Maiden's Wish) was popular in his day and remains so in ours. Smutna rzeka (Troubled Waters) is a dark and tragic song. Certainly the Mickiewicz and marginally the Zaleski poems offer much finer fare. Of course, Chopin sang so gloriously in his absolute piano music, perhaps mere words seemed too concrete for his musical imagination and fine poetic discrimination became unnecessary.

Songs, Op. 74 (a selection)

Poseł (The Messenger, words

by Stefan Witwicki) (1830)

Życzenie

(A

Maiden’s Wish, words by Stefan Witwicki) (1829)

Smutna

rzeka (Troubled

Waters, words by Stefan Witwicki) (1831)

Melodia

‘Z gor, gdzie dźwigali’ (Bound ‘neath Their Crosses, words by Zygmunt

Krasiński) (1847)

Śliczny

chłopiec (My

Beloved, words by Bohdan Zaleski) (1841)

Dwojaki koniec (The Lovers, words by Bohdan Zaleski) (1845)

'Życzenie' ('A Maiden's Wish') Op.74.No.1 [1829?]

A MAIDEN’S WISH

Stefan Witwicki

If I were the sun in the sky,

I wouldn’t shine, except for you —

Not over waters or woods,

But for all time

Beneath your dear window and only for you,

If I could change myself into the sun.

If I were a little bird from that grove,

I wouldn’t sing in any alien land —

Not over waters or woods,

But for all time

Beneath your dear window and only for you.

Oh, why can’t I change myself into a little bird?

Stefan Witwicki (1801-1847) was a Polish romantic poet, publicist and author. He was nicknamed 'Mr. Merry' after his greyhound, with whom he enjoyed walking around Nowy Świat in Warsaw.

Karol

Szymanowski (1882–1937)

|

Karol Szymanowsky painted by 'Witkacy' |

Kurpie Songs, Op. 58, to folk texts (a selection) (1930–1932)

Bzicem

kunia (Whip the Horse)

Zarzyjze,

kuniu (Neigh, Horse)

Wysły

rybki (The Fish Are Gone)

Ściani dumbek (Oh, the Oak Is Felled)

INTERMISSION

Mykoła Łysenko (1842–1912

Садок вишневий

коло хати (Cherry

Orchard by the Cottage, words by Taras Shevchenko)

Айстри (Asters, words by

Oleksandr Oles)

Смутної

провесни (Early

in the Sad Spring, words by Lesya Ukrainka)

Мені однаково (It’s All the Same to Me, words by Taras Shevchenko

Wasyl Barwiński (1888–1963

Сон (Dream, words by

Heinrich Heine, transl. Ahatanhel Krymsky)

Ой, люлі, люлі, моя дитино (Hushaby, My Baby, words by Taras Shevchenko

Wiktor Kosenko (1896–1938

Mow,

mow (Говори,

говори, sł. V. Lichaczow, tłum. W. Leftija)

Smutno

mi (Сумний

я, sł. M. Lermontow, tłum. L. Perwomajski)

Jak na

niebie gwiazdеczki (Як

на небі зіроньки, sł. W. Zalizniak)

Zakukała

kukułeczka Закувала зозуленька, słowa ludowe)

Oni stali milcząc (Вони стояли мовчки, sł. W. Strażew, tłum. B. Mordań)

AUGUST 8 4.00 PM

Chamber concert

MARCIN

ZDUNIK (cello)

SZYMON NEHRING (piano)

One of the greatest pianistic talents of the younger

generation, Nehring is the

only Pole to have won the first prize in the Arthur

Rubinstein International

Piano Master Competition in Tel Aviv. This success paved the

way for him

to perform in the world’s most important venues.

He has appeared, among

others, at the Carnegie Hall, Tonhalle Zurich, Elbphilharmonie

Hamburg,

the Palau de la Musica Catalana in Barcelona, the Auditorio

Nacional de

Musica in Madrid, the Berlin Konzerthaus, DR Koncerthuset in

Copenhagen,

Vienna’s Musikverein, Munich’s

Prinzregententheater and Herkulessaal, as

well as the Berlin Philharmonie.

The artist has performed with the majority of Polish

symphony orchestras,

including Warsaw Philharmonic, the Sinfonia Varsovia, the

Polish National

Radio Symphony Orchestra (NOSPR) in Katowice, the Polish

Sinfonia

Iuventus Orchestra, and the NFM Wrocław Philharmonic, as

well as symphony

orchestras from Bamberg, Hamburg, and Hartford, the

Orchestre

Philharmonique de Marseille, Orchestre Pasdeloup, and the

Orchestra of

the Eighteenth Century, under such conductors as Jerzy

Maksymiuk, Jacek

Kaspszyk, Grzegorz Nowak, Antoni Wit, Sylvain Cambreling,

Karina

Canellakis, Pablo Heras-Casado, Marzena Diakun, Lawrence

Foster, Omer

Meir Wellber, Giancarlo Guerrero, John Axelrod, and David

Zinman.

Nehring’s discography includes both Chopin concertos

(with the Sinfonietta

Cracovia under Jurek Dybał and Krzysztof Penderecki).

2024/2025

has seen two new releases featuring this pianist, one

dedicated to musical

minimalism, the other – inaugurating a cycle of

Chopin recordings for the

Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Warsaw, to be continued in the

next season.

Forthcoming is an album of Karol Szymanowski’s

music with NOSPR

under Marin Alsop.

Appearances this season include Vienna’s

Konzerthaus, Prague’s Rudolfinum,

Hamburg’s Laeiszhalle, and a tour of Japan.

Nehring graduated from Prof. Stefan Wojtas’s

class at the Feliks Nowowiejski

Academy of Music in Bydgoszcz. He developed his abilities

with Boris

Berman at Yale University, New Haven (2017–2019).

MARCIN ZDUNIK (cello)

Polish cellist, soloist and chamber musician, whose

repertoire ranges from

the Renaissance to most recent works. He is also an

improviser, arranger, and

composer, invited to appear at such prestigious music

festivals as London’s

BBC Proms, ‘Progetto Martha Argerich’

in Lugano, as well as ‘Chopin and

His Europe’ in Warsaw.

As a soloist he has performed in such well-known venues as

New York’s

Carnegie Hall, the Berlin Konzerthaus, London’s

Cadogan Hall and Prague’s

Rudolfinum. He has frequently appeared with such excellent

orchestras as

Warsaw Philharmonic, the Prague and European Union Chamber

Orchestras,

the Sinfonia Varsovia, and the City of London Sinfonia,

under such major

conductors as Andrey Boreyko, Antoni Wit, and Andres

Mustonen. A major

part of Zdunik’s artistic career is

taken up by collaborations with inspiring

musicians including Nelson Goerner, Rafał Blechacz,

Krzysztof Jakowicz,

Bomsori Kim, Szymon Nehring, Aleksander Dębicz, Katarzyna

Budnik, and

Jakub Jakowicz. During the ‘Chamber Music Connects

the World’ festival,

he had the honour to perform with Gidon Kremer and Yuri

Bashmet.

The cellist’s numerous accolades garnered in international

music competitions

and festivals include the first prize, Grand Prix, and nine

other awards

in the 6th Witold Lutosławski International Cello

Competition in Warsaw. His

discography, which includes Fryderyk-awarded albums,

comprises music

by Johann Sebastian Bach, Joseph Haydn, Robert Schumann,

Mieczysław

Weinberg, and Paweł Mykietyn, as well as Fryderyk Chopin’s

chamber works

(recorded with Szymon Nehring and Ryszard Groblewski).

Composing music is a major aspect of Marcin Zdunik’s

artistic work.

His recent compositions include Cello Concerto ‘Ghosts of

the Past’, Piano

Quartet and Piano Trio, the cantata Cor Jesu for

tenor, choir, and orchestra,

Da Pacem Domine for solo cello and seven

cellos, as well as theatre music.

Zdunik’s teachers included such outstanding musicians

as Andrzej Bauer

and Julius Berger. He also studied musicology at the

Institute of Musicology,

University of Warsaw. He teaches cello classes at the Stanisław

Moniuszko

Academy of Music in Gdańsk and the Chopin University of

Music in Warsaw.

In April 2021 he was granted the title of Professor of Arts.

Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849)

They

opened their concert with a most pleasant and engaging transcription of the Chopin

Waltz in A minor Op.34 No.2 and the familiar Waltz in C minor Op.64. No.2.

Sonata in G Minor for piano and cello, Op. 65 (1846–1847)

Allegro

moderato

Scherzo

Largo

Finale. Allegro

The cello sonata was written for and dedicated to Chopin's close friend, the renowned cellist Auguste Franchomme. Following some initial optimism, after some work developing sonata with Franchomme, the usual disillusion with his compositions set in.

The work began to give him anguish, grief and arduous challenges as no other piece before - well, the first movement has two hundred pages of sketches and notes of intense creative work, failures and trials! This is hardly surprising as Chopin was exploring, even inventing a forward thinking 'late style', a novel harmonic world and idiom more akin to that of German models such as Schumann, Mendelssohn and even the later Brahms. The high emotionalism of Franck is also prefigured. And yet at times the extremely demanding piano writing hearkens back to the youth of his piano concertos. Also his relationship with George Sand was undergoing severe pressure owing to her increasing antagonism at Nohant towards her son, the painter Maurice. This could account partly for its overall intensely meditative and introspective psychic landscape. It was the last work to be published in his lifetime.

Fortunately for us Chopin was an obsessive letter writer and wrote enormously long, generous and newsy letters to his family in Warsaw (with a quill dipped in ink dried with fine grain sand remember!). They indicate the remarkable encyclopedic nature of his roving mind. 'I am in some strange world ... I am in an imaginary space.' He is far more than a great composer this man, a genius.

On Sunday, 11 October 1846 from George Sand's domain Ch de Nohant, he sat at the little table next to the piano to write when 'they' had gone out for a drive. He wrote, in a type of internal stream of consciousness monologue, of the fine vendage or grape harvest especially in Burgundy, of countryside rambles on which he was not particularly keen, an eccentric dog named Marquis who refuses to eat or drink from gilded bowls and impulsively overturns them.

He also described, among other scientific wonders, of his marveling at the discovery of a new planet (Neptune) by the French astronomer Urbain le Verrier merely by astronomical mathematical calculation. Musical reflections and gossip dominate concerning the fascinating history of Covent Garden Opera in London, the Paris Opera (and news of two ladies dueling over the young, handsome baritone Coletti). He also writes of the activities of the Royals and their lavish activities with 17 carriages.

He profoundly laments the death of the giraffe in Warsaw zoo (Europe in the nineteenth century was fascinated by this extraordinary animal which inspired all sorts of poems, paintings and interior decoration, including pianos!). Chopin expresses a wish not to be reminded of death.

|

French print of a giraffe from 1849

I would like to fill my letter with the best news, but I know nothing other than the fact that I love you and love you. I play a little, write a little. Now I am satisfied with my Cello Sonata, the next time not. I throw it into the corner, then I gather it up again. I have three new Mazurkas...' After salutations and embraces for everyone [...] It is five, and already so dark that I practically can't see. I will end this letter. [...] I embrace you most heartily, and I kiss Mama's little hands and feet. Ch.

George Sand describes his behavior during the white heat crucible of his creations: 'He shut himself up in his room for whole days, weeping, walking about, breaking his quills, repeating or altering a bar a hundred times, writing it down and erasing it as often, and starting over the next day with a scrupulous and desperate perseverance. He would spend six weeks on one page, only to return to it and write it just as he had on the first draft.'

The sonata is a great masterpiece and our duo were at home with the introspective, passionate intensity of this mature work. The pattern of lyrical themes transformed into passionate utterances in the extensive opening Maestoso movement were accomplished with convincing, compelling, energy and expressiveness. Soul searching and emotional resistance were present at once. The phrasing was as passionate as one would anticipate.

Nehring was impressively accomplished in the virtuosic, formidable piano part as Chopin's melodic gift soared effortlessly above us on the cantabile cello. The typically Chopinesque Scherzo was painted in all its shifting moods and jagged dance rhythms so well on the piano. The 'trio' that lies at the centre is one of the most beautiful melodies Chopin ever wrote for cello. It wings above a gently oscillating piano accompaniment. This was most ardent music-making.

The beauty of the poignant, ardent Largo cantilena on the cello became a moving and consoling contemporary commentary on the tragic situation humanity finds itself beset in the war-torn present. Here is a deeply romantic love poem.But energetic life returns in the dotted rhythms of the Finale. Allegro which then modulates into melancholic reflections. The tempestuous coda, concluding in C minor, offers no great consolation to the tragedy that has unfolded. The arabesque phrasing created imagery in my mind depicting a love scene set in a picturesque Italian spa. The heart speaks as in the moving yet passionate Chekov story The Lady and the Little Dog. There was an exciting, dramatic building to an emotional climax of high voltage heat.

Nehring and Zdunik were successful on all levels at communicating the deep national and personal sadness that pervades this work. Chopin and Sand at the time were suffering the unraveling of their extraordinary love, the disintegration of their creative literary and musical world and its former fruitful symbiosis.

Chopin

always brings to my mind the poetry of John Keats (1795-1821). The final stanza

of his Ode on Melancholy (1820) seems so appropriate for this

late work of Chopin - and not only this work.

She

dwells with Beauty—Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding

adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay,

in the very temple of Delight

Veil'd Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though

seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy's grape against his palate fine;

His

soul shalt taste the sadness of her might,

And

be among her cloudy trophies hung.

INTERMISSION

|

Polonaise in C Major for piano and cello, Op. 3 (1829–1830)

|

Chopin sketched by Princess Eliza Radziwill at Antonin en route to Duszniki Zdroj 1826. |

They then might listen to excerpts from the surprisingly complex music that his host, Prince Antoni Radziwiłł, had composed to Faust (Mephisotopheles and Gretchen - music of the sacred and profane). In the evening Chopin showed off his skills as a pianist and duetted with the cellist prince.

But above all, he composed. He was working on the Trio in G minor Op.8, which would be dedicated to Antoni Radziwiłł, and also the Introduction and Polonaise brillante in C major, Op. 3. Chopin knew and loved the cello repertoire, especially the superb playing of the renowned cellist Jozef Merk in Warsaw.

And more to Tytus: ‘While I was staying with him, I wrote there an alla polacca with a cello part. Nothing but baubles to dazzle, for the salon, for the ladies. I wished you see, that Princess Wanda learn to play it. I was supposed to have been giving her lessons during that time. A young thing, 17 years old, pretty, and, by my word, it was nice to help her place her little fingers on the keys. But all joking aside, she has a lot of genuine musical feeling, such that you don't have to tell her to make a crescendo here, a piano there, and 'faster here, and slower there', and so forth.' (At the time she was actually 21 and Chopin was only 19 himself!)

More of Chopin’s

works were transcribed for cello and piano. The Prelude No. 2 in A- minor, No.4 in E minor and No.6 in B minor were all affectingly rendered.

Grand Duo Concertant in E Major on a theme from Giacomo Meyerbeer's opera ‘Robert le diable’ for piano and cello

B 70 (1832–1833)

The Grand Duo concertant in E major (1838) by Chopin based on themes from Robert le diable by Meyerbeer for four hands, originally written in Paris for piano and cello. The work is one of the most marginal works in the Chopin oeuvre. His friend the cellist Auguste Franchomme played it and supposedly gave him constructive advice on the cello writing. Hm…

Schumann treated the Duo rather favourably, emphasising in his review its ‘grace and refinement’, but calling its style ‘low’ and ‘salon’. Is this necessarily a negative matter considering the almost too serious attitude to the choice of classical music we sometimes choose to perform. To quote the title of a piece from Schumann's Kinderszenen that I would apply to many present concert programmes - Fast zu Ernst (Almost too serious). At the same time, he wondered how much Chopin there was in this music and how much Franchomme. He arrived at the conviction that the latter’s role was mainly to nod at the former’s suggestions. In the extant manuscript, though the piano part is written in Chopin’s hand, the cello part is in the hand of Franchomme.

The elaborate writing for piano in style brillante is a real treat and clearly meant by Chopin to please his fashionable Parisian audience rather than make them think. The Grand Duo Concertant was dedicated to a sixteen-year-old young lady, Miss Adèle Forest. She was the daughter of an amateur cellist friend of Franchomme’s and a pupil of Chopin.

We were given charming melodies but the overall effect was not as joyfully and romantically uplifting as the great works performed at the outset. The encore was the deeply moving Lento con gran espressione Nocturne in C sharp minor WN 3

AUGUST 7 8.00

PM

PIOTR ANDERSZEWSKI

Regarded as one of the outstanding musicians of his generation, Piotr Anderszewski

appears regularly in recital at many of the major concert venues

around the world.

Throughout his career he has concentrated mostly on the classic German/

Viennese repertoire encompassing Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann and

Webern. He is also drawn to 20th-century Central European music, particularly

that of Szymanowski and Janaček. He chooses his repertoire carefully,

only playing pieces to which he feels he can contribute in an original and

personal way.

Anderszewski has played with many of the world's great symphony orchestras,

though in recent years he has placed special emphasis on simultaneously

playing and directing. In this manner, he has recorded Mozart with

the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, and

the Sinfonia Varsovia, as well as Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 1 with the

Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen.

Piotr Anderszewski's discography has grown slowly but steadily over the

years. Since 2000 he has been an exclusive artist with Warner Classics (previously

Virgin Classics). His first recording for